We know we want it. We want to see through other people’s eyes, have their experiences, stand in their shoes. That’s the unspoken promise of the movies, and as the unsettling prospect of computer-generated virtual reality creeps closer, it is possible that millions now living will know exactly what it feels like to be somebody else.

“Strange Days,” which takes place on the last two days of 1999, shows us a Los Angeles torn by crime and violence, where the ultimate high is to “jack in” by attaching a “squid” to your skull – a brain wave transmitter that creates the impression that you are having someone else’s experiences. The squid software tapes the lives of other people and plays them back. The movie shows how it works in an opening scene of savage kinetic energy, as a tapehead goes along on an armed robbery, vicariously sharing the same experience until the robber falls off a rooftop to his death.

The tape is for sale, but Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) doesn’t want to buy it. He doesn’t deal in “blackjack” – the word for snuff films. This is a scruple “Strange Days” does not share, and some of its scenes are deeply disturbing, involving the audience as voyeurs during scenes of death. But isn’t that what we do during all the thrillers we attend? Get entertained by the sight of violent action? By making the process explicit, “Strange Days” requires us to think about it, which is more than all but a few movies can or attempt to do.

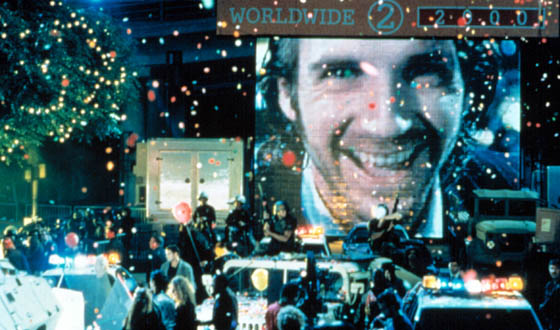

The movie paints a Los Angeles that stands midway between the futuristic nightmare of “Blade Runner” and the mean streets of 1940s film noir. Roaming gangs rule the city. Armored limousines protect the rich. Santa gets mugged on Hollywood Boulevard. “Jacking in” is the new drug of choice, and Lenny Nero is addicted to it himself; he likes to play back tapes of happier days, when he was still with Faith (Juliette Lewis), the woman he loved. The camera caresses Fiennes’ face during these VR sessions; his face reveals surrender to pleasure as he forgives himself everything.

But Faith has split. Now she belongs to Philo Gant (Michael Wincott), who manages rock stars, including Jeriko One, who was “one of the most important black men in America” – until he was shot dead, inspiring riots. Lenny wants her back. He also needs money, desperately. Fiennes plays him as a wheedling con man, forever offering “the Rolex off my wrist” to tough guys who much rather would beat him to a pulp. Lenny used to be a cop, but now he’s a loser, surviving by selling contraband tapes and not asking too many questions about how the “playback” was obtained.

Lenny leads us into grungy nightclubs and scummy hotels, dealing with the pathetic needs of his customers. In a set-up scene in a club, he sells playback to a timid businessman, seductively explaining the technology (“This is not like TV, only better. This is like a piece of someone’s life – straight from the cerebral cortex”).

He lets him have a taste, and we see the mark’s face as he turns soft and narcissistic; he thinks he’s a teenage girl having a shower. Then Lenny points out a couple dancing on the other side of the room.

“How’d you like to be him? How’d you like to have a hot girlfriend like that? How’d you like to be her?” The movie is a technical tour de force. Director Kathryn Bigelow (“Blue Steel“) and her designers and special-effects artists create the vision of a city spinning out of control. Cinematographer Matthew F. Leonetti’s point-of-view shots are virtuosic (especially one in which a character falls from a roof in an apparently uninterrupted take). The pacing is relentless, and the editing, by Howard Smith, creates an urgency and desperation.

Working from a screenplay by Jay Cocks and James Cameron (director of the “Terminator” films), Bigelow turns scenes like this into a critique of the central paradox of virtual reality: You cannot share someone else’s reality without abandoning your own. As the “virgin brain” in the nightclub experiences the sample tape, he watches – and we watch him, defenseless and without inhibition.

It’s creepy.

Other scenes go much further, exploring more twisted horrors. In one, which is disturbing and graphic, a man attacks a female victim after first forcing her to wear the headpiece – so that she experiences her own death through his eyes. It’s revealing, how a scene like that seems so much more sad and distressing than the more graphic scenes of violence we see all the time in the movies: Bigelow is able to exploit the idea of what is happening; she forces her audience to deal with the screen reality, instead of allowing us to process it as routine “action.” The plot is in the noir tradition, with updates out of recent headlines. Although Jeriko One’s murder has pushed the city into anarchy, Lenny Nero’s priorities are private. He wants to raise some money, maybe because that will increase his stature in Faith’s eyes.

Nero gains a companion for his quest: Mace (Angela Bassett), who drives an armored limo, and met Lenny when her husband was murdered.

He was the cop who comforted her kids. She sees through his scam-artist’s facade and saves his skin.

“Strange Days” does three things that will make it a cult film.

It creates a convincing future landscape; it populates it with a hero who comes out of the noir tradition and is flawed and complex rather than simply heroic, and it provides a vocabulary. Look for “tapehead,” “jacking in” and the movie’s spin on “playback” to appear in the vernacular.

At the same time, depending more on mood and character than logic, the movie backs into an ending that is completely implausible.

The police commissioner’s sudden appearance on the scene is miraculous. And Bigelow begins a riot and then forgets about it, segueing into a New Year’s Eve celebration as if you can turn off anarchy like water from a tap.

What stays from the movie are not the transient plot problems, however, but the overall impact. This is the first movie about virtual reality to deal in a challenging way with the implications of the technology. It’s fascinating the way Bigelow is able to suggest so much of VR’s impact (and dangers) within a movie – a form of VR that’s a century old. As the character Faith observes: “One of the ways movies are still better than playback – the music comes up, and you know it’s over.”