If you find yourself in New Orleans on a bad day in the winter, after dark, when it is drizzling and cold and you are on one of the back streets of the French Quarter, you are likely to have one of two reactions. You may be uncomfortable and unhappy. Or you may be wrapped in a delicious melancholy, savoring the damp and the loneliness because it creates the perfect mood for melodramatic gothic excess. You are, in other words, either a pragmatist or a romantic.

“Storyville” is a movie for people who like New Orleans better when it is dark and mysterious. It is for romantics. It is not for pragmatists, who will complain that the characters do not behave according to perfect logic, and that there are holes in its plot.

They will be right, of course – this is not an airtight movie – but they will have missed the point, and the fun.

The movie is a lurid example of the genre of Southern gothic excess, a story of feckless youths and crooked politicians and dangerously seductive women and secrets that creep down through the generations with their tails between their legs. It is altogether proper that Jason Robards is in the movie; he is never more at home than when playing a corrupt old patriarch, bourbon in hand, advising the young folks on how to sell their souls for the best dollar.

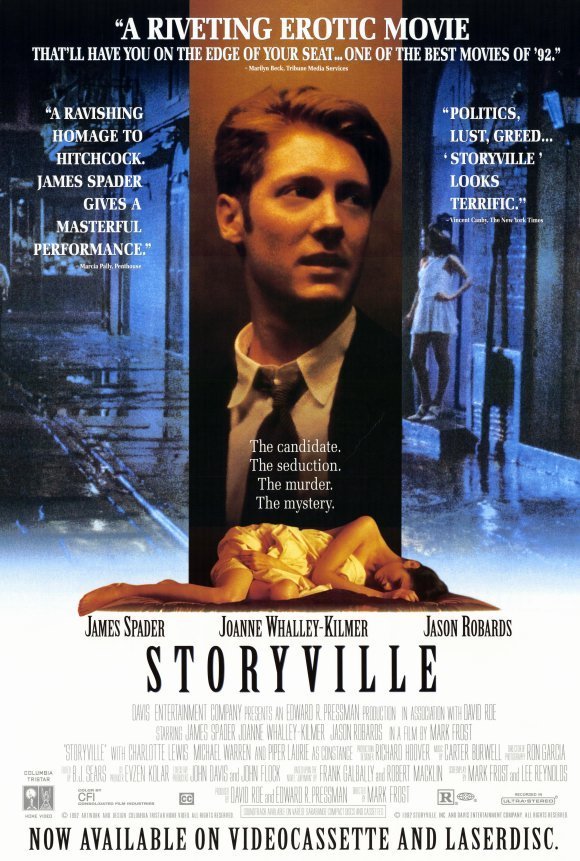

Robards represents the older generation in “Storyville,” although his exact relationship with the film’s hero is left murky until the very end. The hero is played by James Spader, an actor who is unexcelled at portraying lazy-eyed, hedonistic narcissists; this time, he’s a young man running for Congress, although his sense of personal immunity is so complete that he suspects nothing when a beautiful Vietnamese woman (Charlotte Lewis) invites him to visit her Jacuzzi on one of those dreary nights when all the sins are taking place indoors.

Is she really attracted to him? Or is she acting under orders from her evil father? Or is the devious Robards somehow involved? And what to do with the dead body (none of the above) which eventually emerges from Spader’s midnight rendezvous? Those are questions of interest to the other two women in the candidate’s life: His birdbrained wife, who has been on hold for years, and his former lover (Joanne Whalley-Kilmer), who is now the prosecuting attorney, and thinks he may be guilty of murder.

Because the story is set in New Orleans, none of these mysteries can be solved simply by examining the current generation.

There are secrets of the past to rummage through, including the mysterious suicide of Spader’s father, and the fate of some missing documents. And there are additional complications in the present, involving the activities of a pornographer (Charles Haid) whose subjects are both less and more than they seem.

The movie was directed and co-written by Mark Frost, one of David Lynch’s key collaborators on “Twin Peaks,” who started on this screenplay a couple of years before the Lynch project. You can see something of the same sensibility – the willingness to follow a tangled labyrinth of evil and deception as it spirals down through the generations. The difference is that Frost’s “Storyville” takes its story seriously, or at least pretends to, while the “Twin Peaks” projects are at pains to distance the filmmakers from the material.

With Lynch’s recent work, it’s as if he wants you to know he’s superior to the material. Frost doesn’t mind being implicated – he likes this kind of stuff, and plunges into the dark waters of his plot with real joy.

So did I. There is a scene that helps illustrate my enjoyment. Spader goes to visit the beautiful Vietnamese woman, who lives on an upper floor on a deserted street in the Quarter. A crooked vice cop, lurking in the shadows, makes note of the candidate and his destination. There are two ways to read this scene. The pragmatist could scornfully point out (a) how stupid a political candidate would have to be in order to attend such a rendezvous in the middle of his campaign, and (b) how convenient that the vice cop would be stationed in the very spot to see him.

The gothic melodramatic romanticist, on the other hand, would view the scene in this way: (a) how wonderfully bold and reckless for the hero to follow his heart into danger, down mean, wet streets to a passionate rendezvous, and (b) no shot of a sinister man in a shadowy doorway is ever completely unnecessary.