In a sour, gray city, filled with pale drunken salarymen and parading flagellants, everything goes wrong, pain is laughed at, businesses fail, traffic seizes up and a girl is made into a human sacrifice to save a corporation. Roy Andersson’s “Songs From the Second Floor” is a collision at the intersection of farce and tragedy–the apocalypse as a joke on us.

You have never seen a film like this before. You may not enjoy it but you will not forget it. Andersson is a deadpan Swedish surrealist who has spent the last 25 years making “the best TV commercials in the world” (Ingmar Bergman) and now bites off the hand that fed him, chews it thoughtfully, spits it out and tramples on it. His movie regards modern capitalist society with the detached hilarity of a fanatic saint squatting on his pillar in the desert.

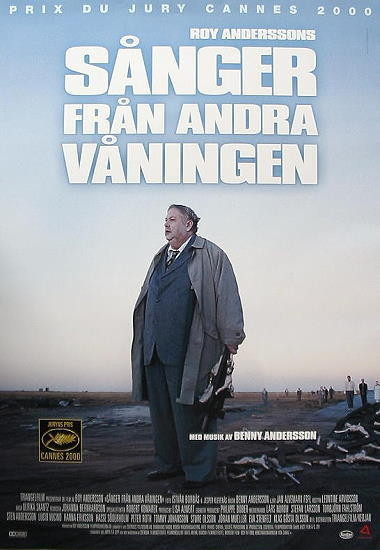

I saw it at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival. Understandably, it did not immediately find a distributor. Predictably, audiences did not flock to it. When I screened it at my 2001 Overlooked Film Festival, there were times when the audience laughed out loud, times when it squinted in dismay, times when it watched in disbelief. When two of the actors came out onstage afterward, it was somehow completely appropriate that one of them never said a word.

I love this film because it is completely new, starting from a place no other film has started from, proceeding implacably to demonstrate the logic of its despair, arriving at a place of no hope. One rummages for the names of artists to evoke: Bosch, Tati, Kafka, Beckett, Dali. It is “slapstick Ingmar Bergman,” says J. Hoberman in the Village Voice. Yes, and tragic Groucho Marx.

The film opens ironically with a man in a tanning machine–ironic, because all of the other characters will look like they’ve spent years in sunless caves. It proceeds with a series of set-pieces in which the camera, rarely moving, gazes impassively at scenes of absurdity and despair. A man is fired and clings to the leg of his boss, who marches down a corridor dragging him behind. A magician saws a volunteer in two. Yes. A man with the wrong accent is attacked by a gang. A man burns down his own store and then assures insurance inspectors it was arson, but as they talk we lose interest because outside on the street a parade of flagellants marches past, whipping themselves in time to their march.

There is the most slender of threads connecting the scenes–the arsonist is a continuing character–but Andersson is not telling a conventional story. He is planting his camera here and there in a city that has simply stopped working, has broken down and is cannibalizing itself. It is a 20th century city, but Andersson sees it as an appropriate backdrop for the plague or any other medieval visitation. And its citizens have fallen back on ancient fearful superstition to protect themselves.

Consider the scene where clerics and businessmen, all robed for their offices, gather in a desolate landscape as a young woman walks the plank to her death below. Perhaps the sacrifice of her life will placate the gods who are angry with the corporation. We watch this scene and we are forced to admit that corporations are capable of such behavior: That a tobacco company, for example, expects its customers to walk the plank every day.

Is there no hope in this devastation? A man who corners the market in crucifixes now bitterly tosses out his excess inventory. “I staked everything on a loser,” he complains. Does that make the movie anti-Christian? No. It is not anti-anything. It is about the loss of hope, about the breakdown of all systems of hope. Its characters are piggish, ignorant, clueless salarymen who, without salaries, have no way to be men. The movie argues that in an economic collapse our modern civilization would fall from us and we would be left wandering our cities like the plague victims of old, seeking relief in drunkenness, superstition, sacrifice, sex and self-mockery.

Oh, but yes, the film is often very funny about this bleak view. I have probably not convinced you of that. It’s funny because it stands back and films its scenes in long shot, the camera not moving, so that we can distance ourselves from the action–and we remember the old rule from the silent days: comedy in long shot, tragedy in closeup. Close shots cause us to identify with the characters, to weep and fear along with them. Long shots allow us to view them objectively, within their environment. “Songs From the Second Floor” is a parade of fools marching blindly to their ruin, and for the moment we are still spectators and have not been required to join the march. The laughter inspired by the movie is sometimes at the absurd, sometimes simply from relief.