I met Patty Hearst twice last spring at the Cannes Film Festival, once in a movie, and once in a restaurant. The effect was unsettling.

In the movie, “Patty Hearst,” she was a quiet, desperate person, so lost in her ordeal that she had no clear idea of any of her motives. A person willing to hold up banks and brandish machineguns simply because of peer pressure from terrorists who had forced her to join their group. In person, she was a pleasant woman in her 30s, joking about how she was trying to trade “Patty Hearst” buttons for festival T-shirts.

I talked to her for awhile, then drifted over to the corner of the room where I looked at her and tried to reconcile the two images, and finally realized that it was going to be impossible. Nothing in her previous life, and now nothing in her subsequent life, had any connection with the events that made Patty Hearst, at the age of 19, into the most famous fugitive in America.

Hearst was kidnapped by something called the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974, and the case and its aftermath, including her famous legal ordeal, lasted until 1979. Even today, it is hard for people to place it – I saw an article mentioning Patty as a figure of the ‘60s. And I doubt if the case has gone into any American history textbooks, since what did it grow out of, where did it lead, what did it prove? It was all just a very odd footnote to history.

And yet the footnotes are sometimes where you find the human interest story. By what process could the heiress of America’s most famous newspaper family, raised in a conventional upper-class Roman Catholic household and embracing most of the values of her parents, be transformed into the person we saw on TV in those days, brandishing a machinegun and shouting revolutionary slogans? Many children of privilege joined the “revolution,” but Hearst was kidnapped. What happened then? That’s the question director Paul Schrader wants to consider in this movie, and to answer it, he reconstructs the physical and mental ordeal that Hearst went through after her kidnapping. She is yanked out of a quiet evening at home with her boyfriend (Steven Weed – how the names still have their resonance!) and thrown into the trunk of a car. Then she finds herself inside a darkened closet, where she is held for weeks, until the horizon of her world is limited to the moments when the door opens and its population consists of half-heard voices.

The effect is to remove her entirely from everything she thought she could count on in life. When she is finally taken out of the closet and allowed to see her captors, she isn’t angry, she’s grateful to them for being allowed to look upon their faces. They have created a complete dependency, and from there it is only a matter of time until she identifies with the group and begins to share its aims.

There is a powerful pressure, felt in all of us, to conform to what those around us consider to be proper behavior. Becoming a revolutionary might have been, for her, a form of good manners.

This is one of the oddest films Schrader has ever made. He is ordinarily a filmmaker of passion and kinetic energy, and this is a brooding and pale film, an introspective one that seems determined not to exploit the sensationalism of the case. Schrader is the favorite screenwriter of Martin Scorsese, for whom he wrote “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull” and, of course, “The Last Temptation of Christ.” His own films are about guilt and passion, and they include “Cat People,” “American Gigolo,” and “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters.” When I heard that Schrader was going to film the Patty Hearst story, I thought I knew what to expect, but I was wrong.

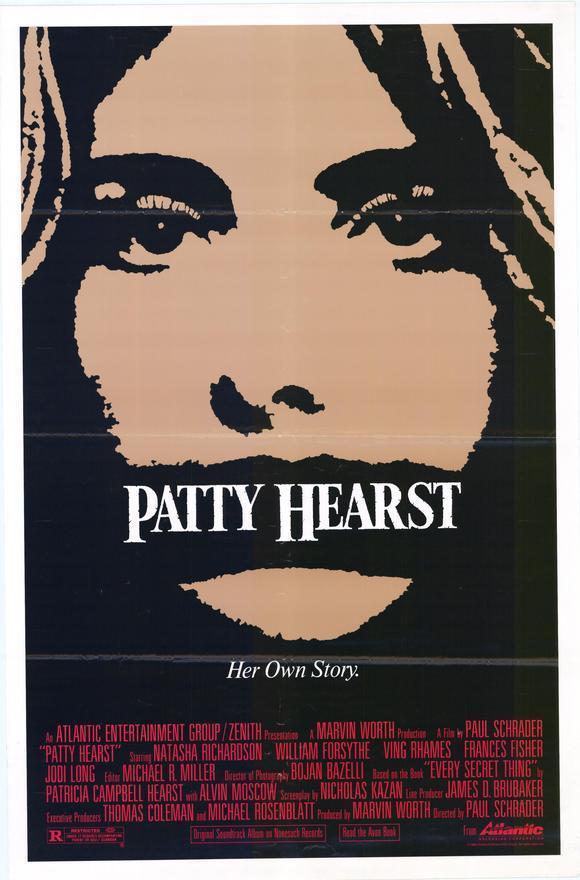

The entire film centers on the remarkable performance by Natasha Richardson as Hearst. She convinces us she is Hearst, not by pressing the point, but by taking it for granted. She is quiet, a little sullen, not forthcoming. She tells people what they want to hear. During all of the tremendous excitement and passion of her ordeal, she hardly seems to be present; this is not a good time for her or a bad time, but a duty.

Schrader also avoids the temptation to make the SLA members into colorful firebrands. They come across as weak, sad people, so hidebound in ideology that they seem shell-shocked. They are all passive personalities, under the will of the leader Cinque (Ving Rhames), who uses revolutionary rhetoric but has created in the SLA a community where no one is free. It’s startling when Schrader re-enacts events we remember from TV (such as Hearst’s bank robbery) or uses actual TV news footage (of the firestorm that engulfed the SLA hideout). This whole story seemed so much more exciting from the outside.