All men live under a sentence of death. They all go sooner or later. But I’m different. I have to go at 6 a.m. tomorrow morning. It would have been 5, but I had a good lawyer…

So muses Woody Allen, in the character of a peasant named Boris, at the beginning of “Love and Death.” The quotation serves as an illustration of the film’s strategy, which is to juxtapose serious matters with a cheerful comic anarchy. Sometimes that’s just a case of setting up a portentous situation and attacking it with a punch line, but Allen frequently finds a way to make his point visually, and “Love and Death” is his most ambitious experiment with the comic possibilities of film.

That’s not to say Woody isn’t still largely a verbal comedian, because he is, and one of the movie’s running gags is an interminable debate about the philosophical and moral choices offered the characters at every turn. But “Love and Death” has been mapped out as a fully thought-through film. It’s a lot more mature than the anything-goes style of earlier Allen movies like “Bananas.”

Allen’s premise is a simple one. Imagine the basic Woody Allen character — shy, incompetent, totally fascinated by women and scared to death of them, secretly romantic — and put him in a time warp that leads back to Russia at the time of Napoleon. Give him a childhood encounter with Death (who looks, of course, as he did in “The Seventh Seal“) and give him a question for Death: “What’s it like after you die? Are there any girls?” Raise him to be a “militant coward,” draft him and send him off to fight the French, and then marry him to a beautiful girl who takes pity on him because (she hopes) he will be shot dead in a duel.

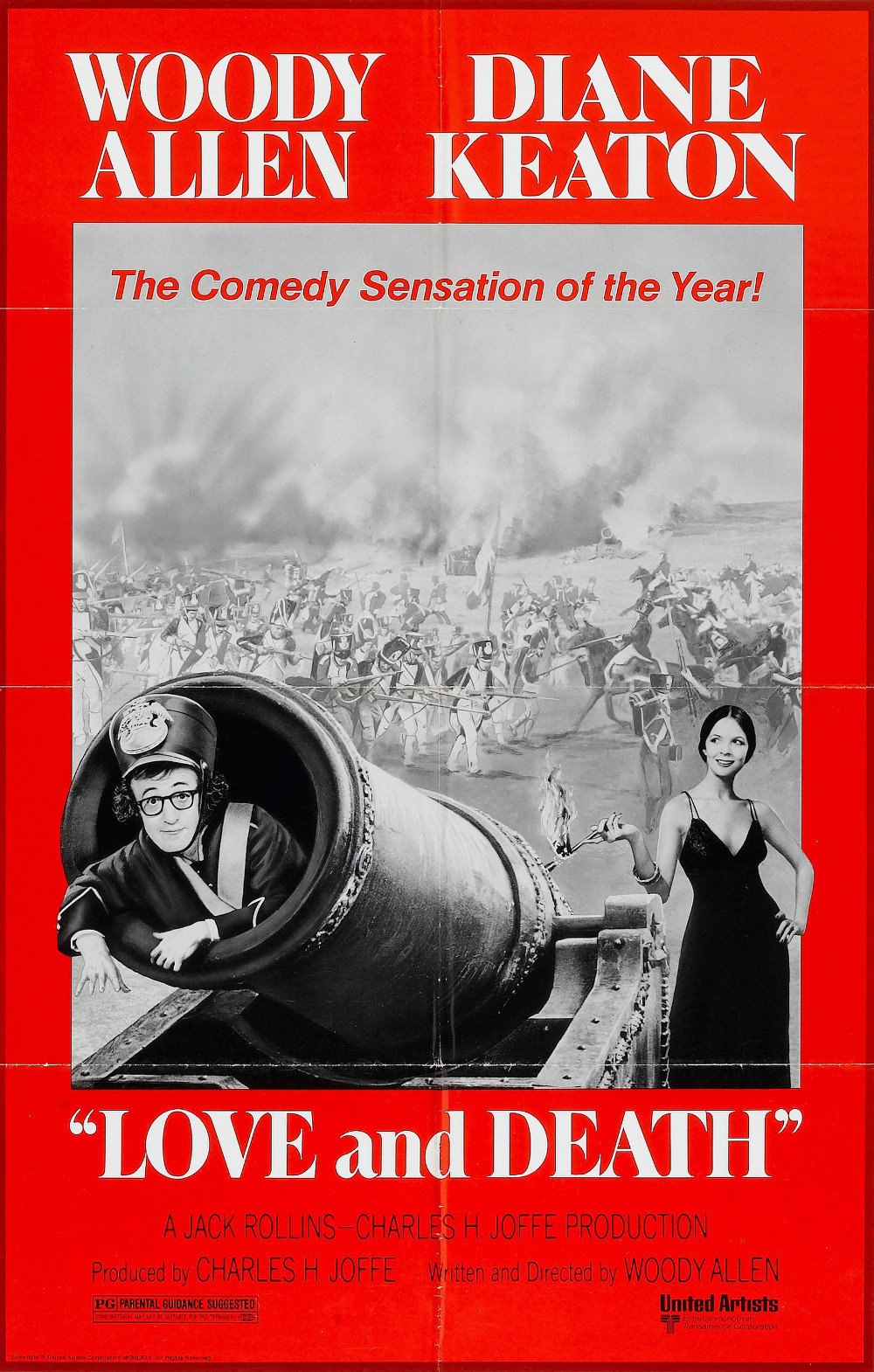

Allen moves through this material like an upside-down bookmark through “War and Peace.” There’s cannon to the left of him, cannon to the right of him and, inevitably, cannon all around him, because to hide on the battlefield, he’s crawled into a cannon. The cannon goes off, Woody becomes a human projectile who destroys four generals without, miraculously, being scratched himself, and he returns as a hero and makes love to the beautiful Countess Alexandrovna. “You are a great lover!” she declares “Thanks,” he says. “I practice a lot when I’m alone.”

The movie’s funniest sequence comes after he marries the beautiful Sonia (Diane Keaton) and together they set out to impersonate Spanish nobility and assassinate Napoleon. This leads to a scene in which Allen konks Keaton on the head several times in a hilarious steal from Chaplin, and then to an encounter in a boudoir when Allen is paralyzed by yet another moral crisis.

If Mel Brooks tries (usually succeeding) to keep us laughing at any cost, Woody Allen takes a quieter approach. We begin to like his screen persona. He’s sweet, he wants to do the right thing, he represents the possibility that simplicity still can prevail in the world. And he’s a perfect foil for the Diane Keaton character, who always wants every situation both ways, plus options. Miss Keaton is very good in “Love and Death,” perhaps because here she gets to establish and develop a character, instead of just providing a foil, as she’s often done in other Allen films.

The best parts of “Love and Death” shouldn’t, of course, be revealed here. Comedy’s hard to review for that reason. You don’t want to give away the laughs and yet you’re left with little else to talk about. Perhaps I should just point to the acting skill that Allen and Miss Keaton exhibit. There are dozens of little moments when their looks have to be exactly right, and they almost always are. There are shadings of comic meaning that could have gotten lost if all we had were the words, and there are whole scenes that play off facial expressions. It’s a good movie to watch just for that reason, because it’s been done with such care, love and lunacy.