All monster films fall into one of two categories: the kind that takes its time revealing the monster, and the kind that shows you the monster right away and never leaves it for long. Think “Jaws” (fins and scary music for the first hour) as opposed to “Deep Blue Sea” or “Sharknado” (Shark-o-Rama pretty much throughout). Most versions of the King Kong story have fallen into the first category: the 1933 original, the 1976 remake, and Peter Jackson’s three-hour 2005 version unveiled the big ape gradually. “Kong: Skull Island,” on the other hand, introduces Kong after less than half an hour, then keeps him (and lots of other big, scary creatures) front and center throughout the film’s 118-minute running time. There’s even a moment where another character tells a story about Kong battling creatures and the movie cuts to images of Kong battling the creatures, in case you weren’t getting your fill of monster-on-monster action.

I’m not mentioning the difference in approach to condemn the new Kong: quite the contrary. This one—about a team of soldiers and scientists that gets stranded on Skull Island during a mission to map the island’s geological interior with explosive charges, which you absolutely should not do when visiting a place called Skull Island—is a half-magnificent, half-misguided example of a “show me the monster” movie. At its best it reminded me of “The Mysterious Island” and “The Land that Time Forgot,” films that were little more than collections of monster-driven action scenes hitched to a perfunctory story about explorers wandering a jungle, doing stuff they were warned not to do, and getting eaten.

The cast includes a couple dozen people who are basically monster chow and therefore not worth describing here; a World War II airman who’s been trapped on the island for 28 years (woolly-bearded John C. Reilly, who steals the film instantly and never gives it back); a tough, quiet British SAS officer (Tom Hiddleston) who has amazing hair; a Special Forces colonel (Samuel L. Jackson) who develops an Ahab-like obsession with killing Kong; a war photographer (Brie Larson) who looks like a Breck girl and has no meaningful plot function; and a wild-eyed visionary (John Goodman) who believes the earth is hollow and filled with beasts whose existence predates the dinosaurs.

The latter theory was also advanced in Gareth Edwards’ 2014 “Godzilla,” a slow-reveal monster film. As you may have heard, this new Kong inhabits the same universe as Edwards’ “Godzilla” and represents stage two in Warner Bros’ scheme to Marvel-ize the giant monster picture by releasing an interconnected series of films that will build to King Kong fighting Godzilla. Annoyed as I am by the studios’ obsession with “expanded universe” storytelling, it seems tailor-made for films with apes and lizards the size of skyscrapers. I say this with the authority of a man who probably spent months of his childhood making animal and dinosaur figurines fight each other in a sandbox, so don’t even try arguing with me, there’s no point.

The monsters are brilliantly designed and skillfully animated (except for a few shots where Kong looks a tad cartoony), and the army of visual and sound effects artists convince you that that these CGI titans live and breathe and weigh hundreds of tons. The title character tears into his foes with the ferocity of an MMA fighter, even using crude weapons when fists and teeth aren’t enough. His opponents include a giant octopus, a fleet of Huey gunships, and creatures that look like wingless pterodactyls with skull-beak heads. Whenever the action flags, the film stirs more creatures into the humans’ meandering trip across the island, including regular-sized pterodactyls, giant insects, and a battleship-sized water buffalo that might’ve been drawn by Hayao Miyazaki. (Alas, the giant ants described by Reilly’s character never materialize.)

Thing is, though, “Kong: Skull Island” seems uncomfortable with being pure childish fun. And the basic theme articulated in both this movie and Evans’ “Godzilla”—Mother Earth doesn’t belong to us, and She can shake us off like a bad case of fleas if we get too uppity—isn’t enough for the filmmakers, either. Directed by Jordan Vogt-Roberts (“The Kings of Summer”) with a script credited to three writers, the film is set in 1973 during the aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam. At first this seems like a handy way of explaining why the world doesn’t already know about Skull Island (global surveillance satellites were a new thing back in ‘73) while fetishizing mid-century analog technology a la Wes Anderson (there are loving close-ups of 35mm movie and still cameras, vinyl record players, rotary phones, and mainframe computers with magnetic tape spools).

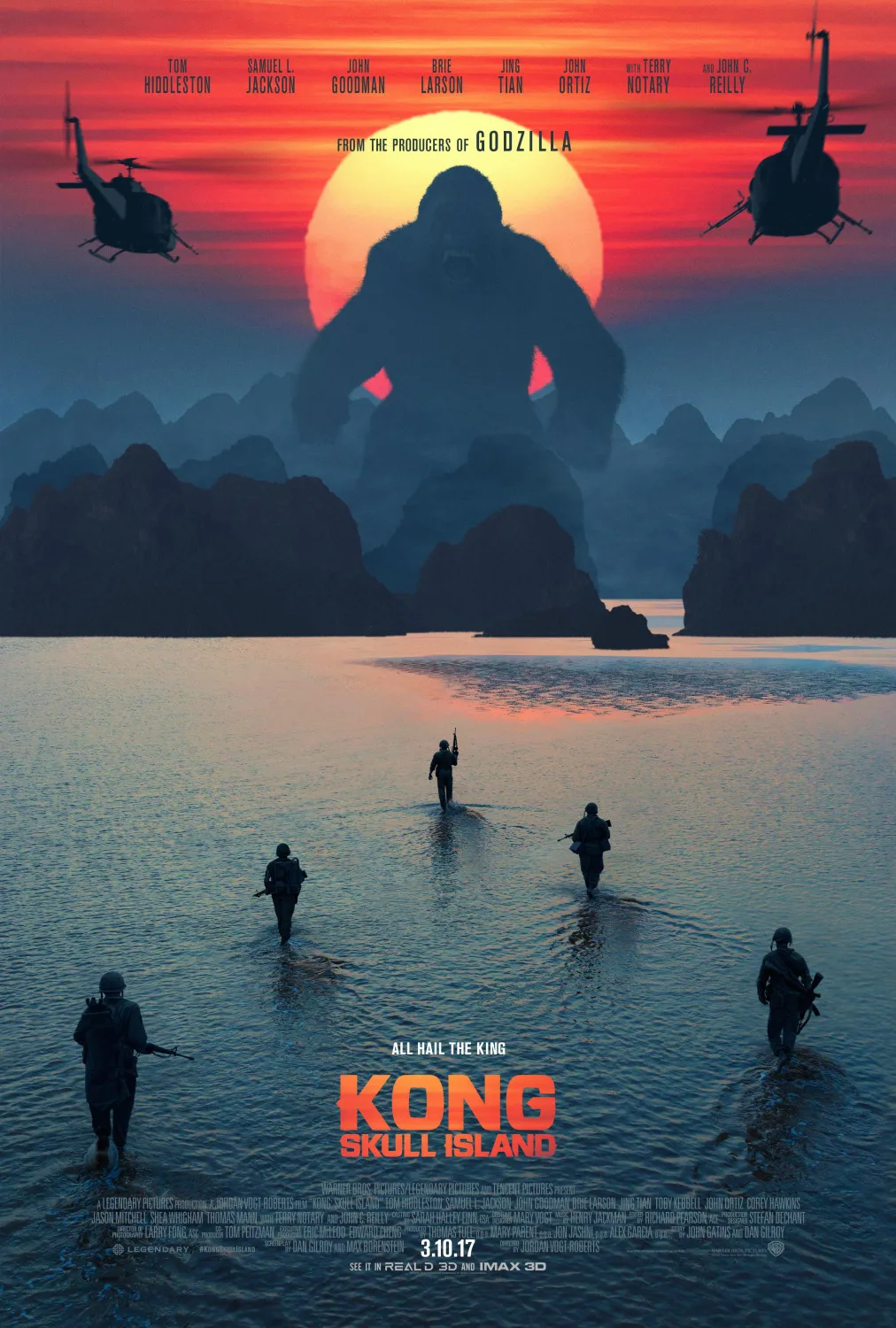

Soon enough, though, you realize that “Kong: Skull Island” wants to make other kinds of statements, though about what it’s not sure. It’s encrusted with layers of pop culture homage and political allegory that keep threatening to add up to something but never do. Vogt-Roberts is on record calling this film a parable of the United States military getting swallowed by the jungles of Vietnam, just in case you didn’t notice all the homages to classic Vietnam movies, particularly Oliver Stone’s “Platoon” and Francis Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” (the IMAX poster for “Kong: Skull Island” is even modeled on Bob Peak’s 1979 poster for Coppola’s film). When Vogt-Roberts isn’t blatantly raiding the most famous ‘Nam movie soundtracks (Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Run Through the Jungle” and The Chambers Brothers’ “The Time Has Come Today” all get a workout) he stirs in undigested chunks of Coppola’s “Apocalypse” inspiration, Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” naming one character Marlow (after the book’s principal narrator) and another, ahem, Conrad. (As a friend put it, “I love the smell of ape palm in the morning.”)

This kind of stuff would consistently land with a ping instead of a thud if the film were weirder and funnier—though to be fair, it is weird and funny at times, especially when serving up vivid throwaway images, such as a Richard Nixon bobble-head doll bouncing on a chopper’s dashboard or an M-60 machine-gunner bracing his tripod against a Triceratops skull. Vogt-Roberts is a rare American director who can tell a joke with a shot. The more random the joke, the funnier it tends to be.

Unfortunately, every time the film’s prankish eye puts a smile on your face, a misjudged line or idea wipes it off. Characters keep making cryptic “meaningful” statements like “We didn’t lose the war, we abandoned it” and “Sometimes the enemy doesn’t exist until you go looking for them,” but these never really sync up with images of Kong surviving a napalm attack or a band of grunts sneaking through a prehistoric killing field.

Meanwhile, the movie’s casually ethnocentric approach of representing Americans as Americans and the cultural “Other” as giant apes, cattle, bugs, and snaggle-toothed demon beasts that come screaming up out of the earth like Vietcong commandos goes unexamined. There are also mute tribespeople who worship Kong as a protector-god. Who knows: there might even be a wider allegory about the Cold War, embedded in the characters’ debates over whether Kong is a good guy or another monster. Is Vogt-Roberts trying to make King Kong a political-mythological emblem of the United States, akin to Godzilla for Japan? Maybe Kong, the last of his kind, is supposed to be the lone superpower, a kindhearted tough guy that only wants to be left alone but keeps getting pulled into other people’s fights, like John Wayne, the Hiddleston character’s childhood hero. Maybe the razor-toothed carnivorous beasts are the communist axis of China and the USSR, and the bugs and plant eaters and tribespeople are unaligned countries. Then again, maybe not.

“Kong: Skull Island” is best viewed on a huge screen with surround sound, through a child’s forgiving eyes. Childhood flashbacks notwithstanding, I like my monster films to have a touch of poetry, and except for a sequence near the end featuring the Aurora Borealis, this one is poetry-deprived. It’s personality-deprived, too. Only Reilly’s wisecracking castaway and a literal-minded lifer played by “Boardwalk Empire” regular Shea Whigham linger in the mind. Kong himself is less a character than a hairy symbol of whatever the film requires, and the requirements change from scene to scene. But you do get to see the big guy slurp octopus tentacles like soup noodles and spike a chopper like a volleyball, and I’d be lying if I said that wasn’t awesome. This is a two-and-a-half star film; the extra half-star is for the creatures, tiny versions of which are surely coming to a sandbox near you.