“I love staying at local homes,” the man says, accepting an offer of hospitality after he misses the last bus back to the city. He has been collecting insects in a remote desert region of Japan. The villagers lead him to a house at the bottom of a sandpit, and he climbs down a rope ladder to spend the night with the woman who lives there. She prepares his dinner, and fans him as he eats. During the night, he awakens to observe that she is outside, shoveling sand. In the morning, he sees her sleeping, her body naked and sparkling with sand. He goes outside to leave. “That’s funny,” he says to himself. “The ladder is gone.”

There is a harsh musical chord at this moment, announcing the harsh surprise of “Woman in the Dunes” (1964), one of the rare films able to combine realism with a parable about life. The man (Eiji Okada) is expected to remain in the pit and join the woman in shoveling sand, which is hauled to the surface in bags by the villagers. “If we stop shoveling,” the woman (Kyoko Kishida) explains, “the house will get buried. If we get buried, the house next door is in danger.”

I am not able to understand the mechanics of that explanation, nor do I understand the local economy. The villagers sell the sand for construction, the woman explains. It is too salty to meet the building codes, but they sell it cheap. But surely there are choices other than living in a pit and selling sand? Of course there is no logic beneath the story, and the director, Hiroshi Teshigahara, has even explained that sand cannot rise in steep walls like those on the sides of the pit: “I found it physically impossible to create an angle of more than 30 degrees.”

Yet there is never a moment when the film doesn’t look absolutely realistic, and it isn’t about sand anyway, but about life. “Are you shoveling to survive, or surviving to shovel?” the man asks the woman, and who cannot ask the same question? “Woman in the Dunes” is a modern version of the myth of Sisyphus, the man condemned by the gods to spend eternity rolling a boulder to the top of a hill, only to see it roll back down.

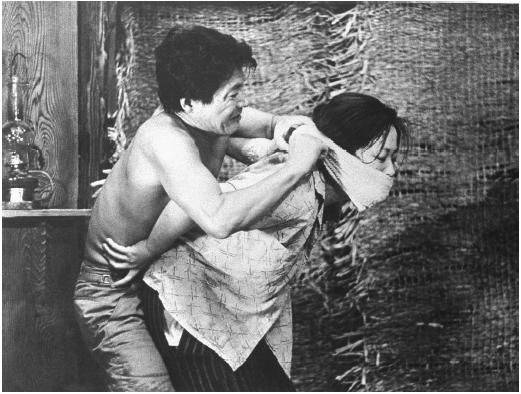

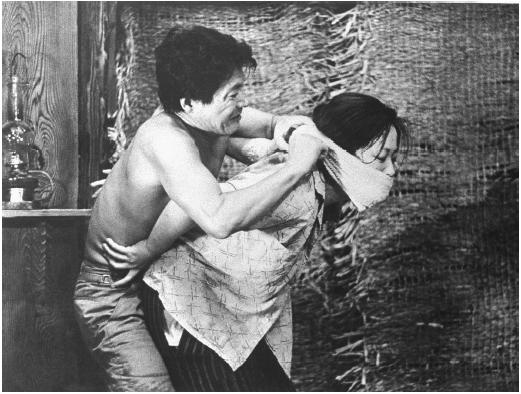

In a way the man has himself to blame. He makes his desert trips to escape He seeks solitude and finds it. The film opens with a montage of fingerprints and passport stamps, and then there is a closeup of a grain of sand as big as a boulder, and then several the size of diamonds, and then countless grains, with the wind rippling their surface as if they were water. There has never been sand photography like this (no, not even in “Lawrence of Arabia“), and by anchoring the story so firmly in this tangible physical reality, the cinematographer, Hiroshi Segawa, helps the director pull off the difficult feat of telling a parable as if it is really happening. The score by Toru Takemitsu doesn’t underline the action but mocks it, with high, plaintive notes, harsh, like a metallic wind. The first time I saw the film, it played like a psycho-sexual adventure. The underlying situation is almost pornographic: A wandering man is trapped by a woman, who offers her body at the price of lifelong servitude. There is a strong erotic undercurrent, beginning with the woman displaying her sleeping form, and continuing through hostility, struggle and bondage to their eventual common ground.

More than almost any other film I can think of, “Woman in the Dunes” uses visuals to create a tangible texture–of sand, of skin, of water seeping into sand and changing its nature. It is not so much that the woman is seductive as that you sense, as you look at her, exactly how it would feel to touch her skin. The film’s sexuality is part of its overall reality: In this pit, life is reduced to work, sleep, food and sex, and when the woman wishes for a radio, “so we could keep up with the news,” she only underlines how meaningless that would be.

The screenplay is by Kobo Abe, based on his own novel, and it reveals the enormity of the situation slowly and deliberately–not rushing to announce the man’s dilemma, but revealing it in little hints and insights, while establishing the daily rhythm of life in the dunes. The pit-dwellers are serviced by villagers from above, who use pulleys to lower water and supplies, and haul up the sand. It is never clear whether the woman willingly descended into her pit or was placed there by the village; certainly she has accepted her fate, and would not escape if she could. She participates in the capture of the man because she must: Alone, she cannot shovel enough sand to stay ahead of the drifts, and her survival–her food and water–depend on her work. Besides, her husband and daughter were buried in a sandstorm, she tells the man, and “the bones are buried here.” So they are both captives–one accepting fate, the other trying to escape it.

The man tries everything he can to climb from the pit, and there is one shot, a wall of sand raining down, that is so smooth and sudden the heart leaps. As a naturalist, he grows interested in his situation, in the birds and insects that are visitors. He devises a trap to catch a crow, and catches no crows, but does discover by accident how to extract water from the sand, and this discovery may be the one tangible, useful, unchallenged accomplishment of his life. Everything else, as a narrative voice (his?) tells us, is contracts, licenses, deeds, ID cards– “paperwork to reassure one another.”

Hiroshi Teshigahara was 37 when he directed “Woman in the Dunes,” which won the jury prize at Cannes and two Oscar nominations. His father had founded a famous school of flower arranging in Tokyo–a school where I once took a few classes, getting just a glimpse of the possibility that to arrange flowers harmoniously could be a triumph of art and philosophy, and a form of meditation. He was always expected to take over management of the school (“a situation ironically similar to that of the protagonist of “Woman in the Dunes,’ the film notes observe). He seems intrigued by variety, and has made documentaries on the boxer Jose Torres and on a wood block artist, has worked in ceramics, directed opera, staged tea ceremonies, and directed seven other feature films. He also, according to plan, took over the flower arranging school.

“Woman in the Dunes” seemed to disappear for years. I tried to rent it for film classes, and couldn’t. At Teshigahara’s school in Tokyo, I was told vaguely by a translator that the master had chosen to look in new directions, instead of back at his old work. But now a fresh print has been released by Milestone, an American company dedicated to rescuing films, and seeing the film in 35 mm., I found it as radical, hard-edged and challenging as when I first saw it.

Unlike some parables that are powerful the first time but merely pious when revisited, “Woman in the Dunes” retains its power because it is a perfect union of subject, style and idea. A man and a woman share a common task. They cannot escape it. On them depends the community–and, by extension, the world.

But is struggle the only purpose of struggle? By discovering the principle of the water pump, the man is able to bring something new into existence. He has changed the terms of the deal. You cannot escape the pit. But you can make it a better pit. Small consolation is better than none.