It is almost always raining in the city. Somerset, the veteran detective, wears a hat and raincoat. Mills, the kid who has just been transferred into the district, walks bare-headed in the rain as if he’ll be young forever. On their first day together, they investigate the death of a fat man they find face-down in a dish of pasta. On a return visit to the scene, the beams of their flashlights point here and there in the filthy apartment, picking out a shelf lined with dozens of cans of Campbell’s Tomato Sauce. Not even a fat man buys that much tomato sauce.

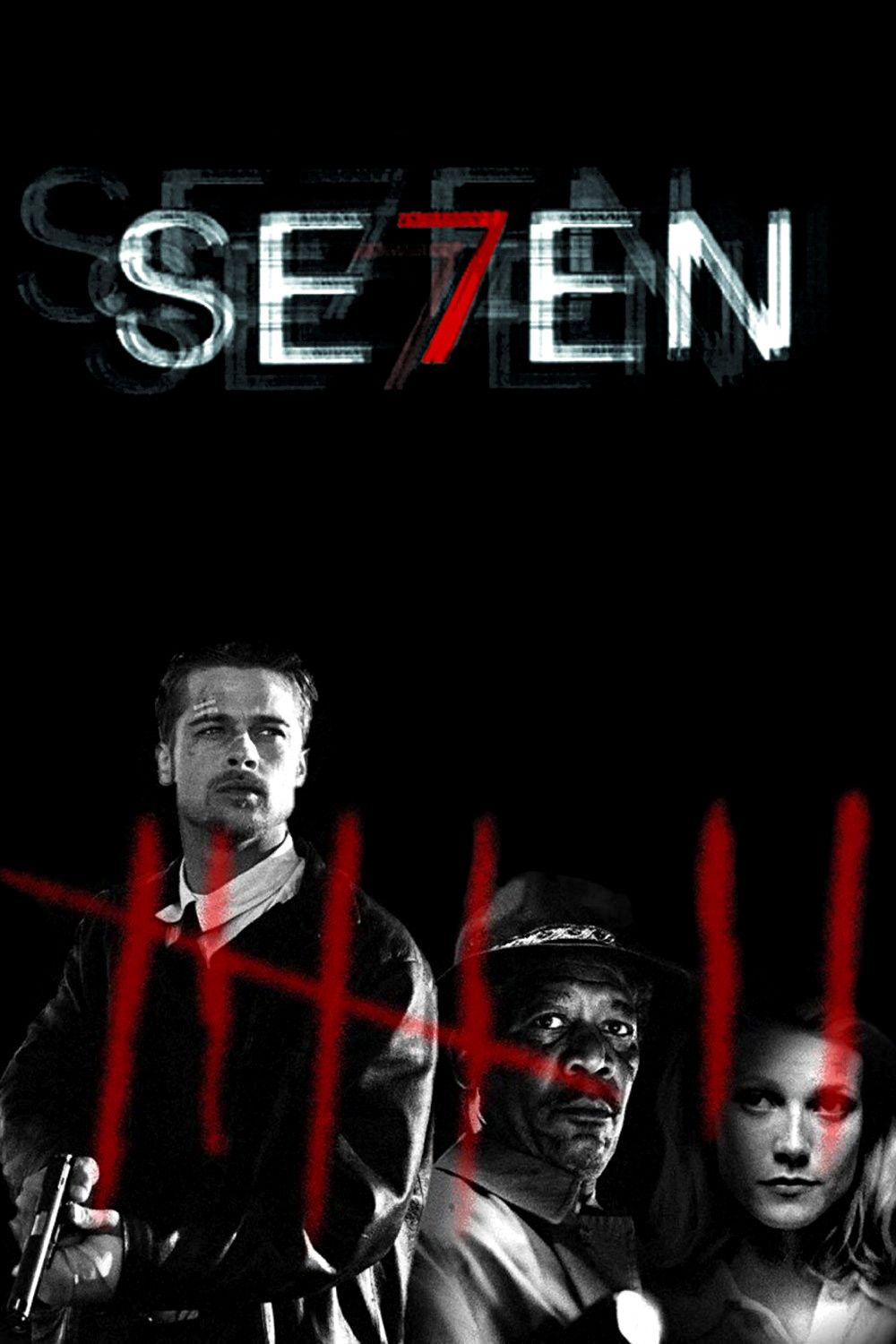

This grim death sets the tone for David Fincher’s “Seven,” one of the darkest and most merciless films ever made in the Hollywood mainstream. It will rain day after day. They will investigate death after death. There are words scrawled at the crime scenes; the fat man’s word is on the wall behind his refrigerator: Gluttony. After two of these killings Mills realizes they are dealing with a serial killer, who intends every murder to punish one of the Seven Deadly Sins.

This is as formulaic as an Agatha Christie whodunit. But “Seven” takes place not in the genteel world of country house murders, but in the lives of two cops, one who thinks he has seen it all and the other who has no idea what he is about to see. Nor is the film about detection; the killer turns himself in when the film still has half an hour to go. It’s more of a character study, in which the older man becomes a scholar of depravity and the younger experiences it in an pitiable and personal way. A hopeful quote by Hemingway was added as a voice-over after preview audiences found the original ending too horrifying. But the original ending is still there, and the quote plays more like a bleak joke. The film should end with Freeman’s “see you around.” After the devastating conclusion, the Hemingway line is small consolation.

The enigma of Somerset’s character is at the heart of the film, and this is one of Morgan Freeman’s best performances. He embodies authority naturally; I can’t recall him ever playing a weak man. Here he knows all the lessons a cop might internalize during years spent in what we learn is one of the worst districts of the city. He lives alone, in what looks like a rented apartment, bookshelves on the walls. He puts himself to sleep with a metronome. He never married, although he came close once. He is a lonely man who confronts life with resigned detachment.

When he realizes he’s dealing with the Seven Deadly Sins, he does what few people would do, and goes to the library. There he looks into Dante’s Inferno, Milton’s Paradise Lost and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It’s not that he reads them so much as that he references them for viewers; it is often effective in a horror film to introduce disturbing elements from literature as atmosphere, and Fincher provides glimpses of Gustav Dore’s illustrations for Dante, including the famous depiction of a woman with spider legs. Somerset sounds erudite as he names the deadly sins to Mills, who seems to be hearing of them for the first time.

What’s being used here is the same sort of approach William Friedkin employed in “The Exorcist” and Jonathan Demme in “The Silence of the Lambs.” What could become a routine cop movie is elevated by the evocation of dread mythology and symbolism. “Seven” is not really a very deep or profound film, but it provides the convincing illusion of one. Almost all mainstream thrillers seek first to provide entertainment; this one intends to fascinate and appall. By giving the impression of scholarship, Detective Somerset lends a depth and significance to what the killer apparently considers moral statements. To be sure, Somerset lucks out in finding that the killer has a library card, although with this killer, thinking back, you figure he didn’t get his ideas in the library, and checked out those books to lure the police.

The five murders investigated by the partners provide variety. The killer has obviously gone to elaborate pains in planning and carrying them out — in one case, at least a year in advance. His agenda in the film’s climactic scene, however, must have been improvised recently. “Seven” draws us relentlessly into its horrors, some of which are all the more effective for being glimpsed in brief shots. We can only be sure of the killing methods after the cops discuss them–although a shot of the contents of a plastic bag after an autopsy hardly requires more explanation. Fincher shows us enough to disgust us, and cuts away.

The killer obviously intends his elaborate murders as moral statement. He suggests as much after we meet him. When he’s told his crimes will soon be forgotten in the daily rush of cruelty, he insists they will be remembered forever. They are his masterpiece. What goes unexplained is how, exactly, he is making a statement. His victims, presumably guilty of their sins, have been convicted and executed by his actions. What’s the lesson? Let that be a warning to us?

Somerset and Mills represent established fiction formulas. Mills is the fish out of water, they’re an Odd Couple, and together they’re the old hand and the greenhorn. The actors and the dialogue by Andrew Kevin Walker enrich the formulas with specific details and Freeman’s precise, laconic speech. Brad Pitt seems more one-dimensional, or perhaps guarded; he’s a hothead, quick to dismiss Freeman’s caution and experience. It is his wife Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow) who brings a note of humanity into the picture; we never find out very much about her, but we know she loves her husband and worries about him, and she has good instincts when she invites the never-married Somerset over for dinner. Best to make an ally of the man who her husband needs and can learn from. Watching the film, we assume the Tracy character is simply a place-holder, labeled Protagonist’s Wife and denied much dimension. But she is saving her impact until later. Thinking back through the film, our appreciation for its construction grows.

The killer, as I said, turns himself in with 30 minutes to go, and dominates the film from that point forward. When “Seven” was released in 1995 the ads, posters and opening credits didn’t mention the name of the actor, and although you may well know it, I don’t think I will either. This actor has a big assignment. He embodies Evil. Like Hannibal Lecter, his character must be played by a strong actor who projects not merely villainy but twisted psychological complexities. Observe his face. Smug. Self-satisfied. Listen to his voice. Intelligent. Analytical. Mark his composure and apparent fearlessness. The film essentially depends on him, and would go astray if the actor faltered. He doesn’t.

“Seven” (1995) was David Fincher’s second feature, after “Alien 3” (1992), filmed when he was only 29. Still to come were such as “Zodiac” (2007) and “The Social Network” (2010). In his work he likes a saturated palate and gravitates toward sombre colors and underlighted interiors. None of his films is darker than this one. Like Spielberg, he infuses the air in his interiors with a fine unseen powder that makes the beams of flashlights visible, emphasizing the surrounding darkness. I don’t know why the interior lights in “Seven” so often seem weak or absent, but I’m not complaining. I remember a shot in Murnau’s “Faust” (1926) in which Satan wore a black cloak that enveloped a tiny village below. That is the sensation Fincher creates here.