You’ve been hoodwinked. You’ve been had. You’ve been took. You’ve been led astray, run amuck. You’ve been bamboozled.

So said Malcolm X, as quoted by Spike Lee in the production notes to “Bamboozled,” his perplexing new film. To Malcolm, the bamboozlers were white people in general, but in Lee’s films they’re the television executives, black and white, who bamboozle themselves in the mindless quest for ratings. The film is a satirical attack on the way TV uses and misuses African-American images, but many viewers will leave the theater thinking Lee has misused them himself.

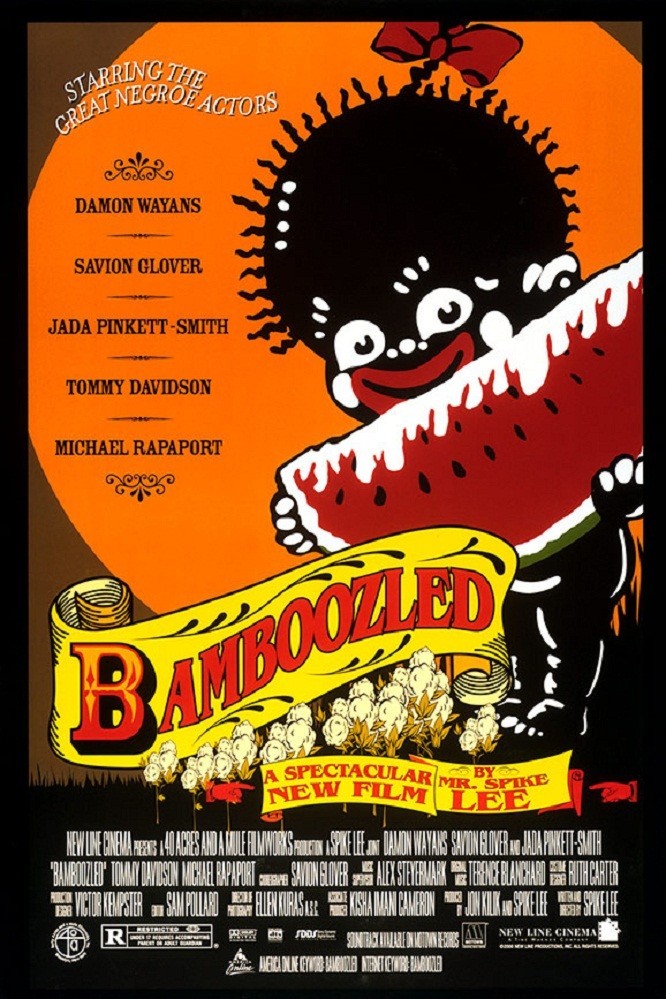

That’s the danger with satire: To ridicule something, you have to show it, and if what you’re attacking is a potent enough image, the image retains its negative power no matter what you want to say about it. “Bamboozled” shows black actors in boldly exaggerated blackface for a cable production named “Mantan–The New Millennium Minstrel Show.” Can we see beyond the blackface to its purpose? I had a struggle.

The movie stars Damon Wayans as Pierre Delacroix, a Harvard graduate who is a program executive at a cable TV network. He works under a boss who is, in his own eyes, admirably unprejudiced: Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport) says Delacroix’s black shows are “too white,” and adds: “I have a black wife and two biracial kids. Brother man–I’m blacker than you.” Well, Delacroix isn’t very black; his accent makes him sound like Franklin Pangborn as a floorwalker. But he’s black enough to resent how Dunwitty and the network treat him (when he’s late to a meeting, his boss says he’s “pulling a Rodman”). In front of his office, he often passes two homeless street performers, Manray (Savion Glover) and Womack (Tommy Davidson). Fed up with the news that he’s not black enough, Delacroix decides to star them in a blackface variety show set in a watermelon patch on an Alabama plantation.

The new show shocks and offends many viewers, but turns into an enormous hit, sending the plot into twists and terrorist turns that are beside the issue. The central questions any viewer of “Bamboozled” has to answer are: (1) How do I feel about the racist images I’m seeing, and (2) Is Spike Lee making his point? I think he makes his point intellectually; it’s quite possible to see the film and understand his feelings. In conversation, Lee wonders why black-themed shows on TV are nearly always comedies; why are episodic dramas about blacks so rare? Are whites so threatened by blacks on TV that they’ll only watch them being funny? An excellent question. And when Lee says the modern equivalent of a blackface minstrel show is the gangsta-rap music video, we see what he means: These videos are enormously popular with white kids, just as minstrel shows were beloved by white audiences, and for a similar reason: They package entertainment within demeaning and negative black images.

Lee’s comments are on target, but is his film? I don’t think so. Lee’s spin on a gangsta-rap video or an African-American domestic comedy might be radically revealing. And what about executives rewriting scenes and dialogue according to their narrow ideas? (Margaret Cho’s concert documentary, “I’m the One That I Want,” tells of executives at CBS asking for rewrites to make the Korean-American comedian “less ethnic.”) To satirize black shows on TV, Lee should have stayed closer to what really offends him; I think his fundamental miscalculation was to use blackface itself. He overshoots the mark. Blackface is so blatant, so wounding, so highly charged, that it obscures any point being made by the person wearing it. The makeup is the message.

Consider the most infamous public use of blackface in recent years. Ted Danson appeared in blackface at a Friar’s Club roast for his then-girlfriend Whoopi Goldberg. The audience sat in stunned silence. I was there, and I could feel the tension and discomfort in the room. In his defense, Danson said the skit had been dreamed up and written by Whoopi. One of his lines was about how he’d invited Whoopi home to dinner and his parents had asked her to clean up the kitchen after the meal. Not funny when Danson said it. If Whoopi had said it about herself, it would have been funny, with an edge. But if Whoopi had said it while wearing blackface? Not funny. After Danson’s flop, comedian Bobcat Goldthwait summed up the mood: “Jesus Christ, Ted, what were you thinking of? Do you think black people think blackface is funny in 1993?” No, and white people don’t, either. Blacks in blackface eating watermelon and playing characters named Eat ‘n Sleep, Rufus and Aunt Jemima fail as satire and simply become–well, what they seem to be. Crude racist caricatures.

I think Spike Lee misjudged his material and audience in the same way Whoopi Goldberg did, and for the same reason: He doesn’t find a successful way to express his feelings, angers and satirical points. When Mel Brooks satirizes Nazis in the famous “Springtime for Hitler” number in “The Producers,” (1960) he makes Hitler look like a ridiculous buffoon. But what if the musical number had centered on Jews being marched into gas chambers? Not funny. Blackface is over the top in the same way–people’s feelings run too strongly and deeply for any satirical use to be effective. The power of the racist image tramples over the material and asserts only itself.