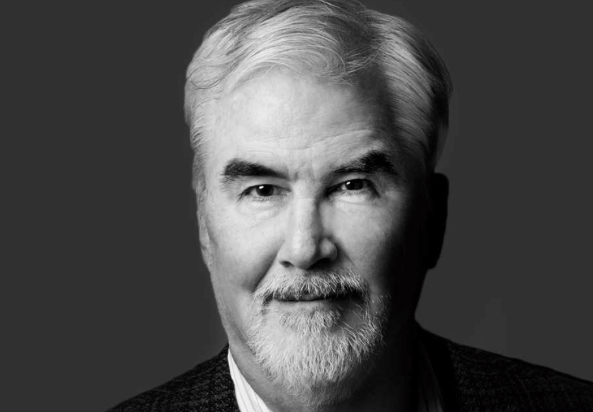

Richard Corliss, who died last week at 71, was one of those people whose importance sneaks up on you. Both his work and his personality were unobtrusive, but both were unforgettable.

A native of Philadelphia, Corliss was spurred to study film after he saw Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal” and realized that movies could do more than just kill time. In the 1960s and ’70s, Corliss wrote for National Review, MacLean’s, and New Times. (The first outlet now seems odd, considering that the publication is sharply conservative and Corliss was a liberal throughout his adult life.) He was mainly known for his film and culture criticism and reporting for Time Magazine, where he’d been a staff writer and film critic (alongside Richard Schickel) since 1980. But he he did a lot more than that. He wrote three books, including one on Stanley Kubrick’s film version of Lolita. He covered the Cannes film festival for more continuous years than anyone except Roger Ebert, and appeared on The Charlie Rose Show 14 times.

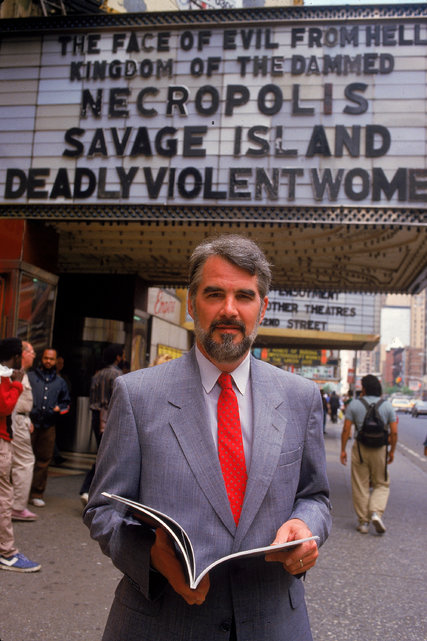

And he was the longtime editor of Film Comment (from 1970-1990; during the second half of that stint he was simultaneously working for Time, amazingly) and is probably still more responsible for shaping the publication’s personality than anyone else. Corliss infused an unabashedly intellectual magazine (Corliss hired Jonathan Rosenbaum as their Paris correspondent) with enough populist touches to draw non-film-buffs (he came up for the idea for the first “Guilty Pleasures” issue with Martin Scorsese, for example). In the pages of Time, Corliss certified the stardom and/or artistic

chops of now legendary entertainers, in ways that pushed them over the

line separating “known quantity” and “American institution.” He called Bette Midler “a 5-ft. 1-in. Statue of Libido carrying a torch with a blue flame.” He was the first journalist to reveal that Tom Cruise, whom he praised in his Time

story as a dynamic and thoughtful actor, was also a dyslexic who

carried around a dictionary so that he could look up unfamiliar words.

Late in his career, Corliss inaugurated a regular column of nostalgic appreciations,

“That Old Feeling,” which revisited subjects that were likely of little

interest to young readers whose present-tense interests drive online entertainment coverage.

What bound all this work together was a quietly stubborn individuality. Corliss was distrustful of anything that seemed like dogma, even though (ironically) his ahead-of-the-curve writing often contributed to what would later seem like a new Received Wisdom.

Corliss was a former student of Andrew Sarris, who probably did more than anybody in the US to popularize the French auteur theory, which held that in cinema, a director is the primary author of a work; at Film Comment, and parenthetically in Time Magazine, Corliss went out of his way to call attention to screenwriters; he even wrote a book about them, “Talking Pictures.” He praised many challenging or difficult films, including some classics of art cinema, but he was also a huge booster of Pixar films and Hong Kong action pictures, including the works of Jackie Chan, whom he considered the artistic and athletic equal of Buster Keaton. One of my favorite Corliss columns argues that the perception of the 1950s as a xenophobic decade in the United States is incorrect. It starts with a list of ten US pop chart hits that are actually adaptions of songs in other languages, then moves on to list plays, films, novels and TV programs from the era that were meant to expand American cultural horizons.

Back in the early ’90s, after he’d left the editorship of Film Comment but was still a contributor, Corliss had one of the great public disagreements with the founder of this web site, one that was recounted in “Life Itself“: over a series of issues, Corliss and Roger Ebert argued about whether the kind of criticism showcased on Roger’s TV show with Gene Siskel could truly be considered criticism. They disagreed sharply—at one point Roger counted up the total number of words verbally expended on a particular film discussed on his TV program and the average word count of a Time magazine review, and concluded they were about equal—but this public clash didn’t affect their friendship.

As every critic does sometimes, Corliss missed the boat on what are now thought of as classic movies (he didn’t like “Do the Right Thing” because he thought it inflamed emotions without really taking a stand on any of the issues it raised) but he championed many more, often in ways that seem prescient today. He got to the heart of what makes “Bull Durham” great by weaving his own baseball fandom into his appreciation of the film as cinema: “Ron Shelton, who spent some years in the minors, has made a movie with

the loping narrative rhythm of a baseball season. This is, after all, a

game of anticipation: waiting to gauge an opposing pitcher’s heat,

waiting for a seeing-eye grounder or a play at the plate. Shelton

locates the tension and the humor between pitches, between ball games,

between the sheets.” Corliss agitated to put Steven Spielberg’s “E.T.”, a low-budget film starring a puppet, on the cover of Time, because he thought it a monumental work on par with “The Wizard of Oz,” and he succeeded—although the story ended up being bumped to the inside of the magazine by the Falklands War. He arguably did more to usher Oliver Stone into the mainstream than any other critic when he penned a lengthy Time cover story about the director’s fourth film, a low-budget war picture stocked with then-no-name actors, “Platoon”: “In vivid imagery and incendiary action, Stone’s film asks of our

soldiers, ‘Am I my brother’s killer?’ The answer is an anguished yes.” Almost 20 years ago Corliss characterized Adam Sandler in words that ring true today: “Adam Sandler is of the new S.N.L. breed. His Cajun Man, Opera

Man and the rest were not varied characters; they were expressions of

one capacious ego. The issue for him was not selling out but finding a

buyer. And Hollywood, ever desperate for performers with male-teen

appeal, bought.”

In researching Corliss before writing this piece, it dawned on me what an immense personal and creative influence he was. I was never close friends with him, but we both belonged to the New York Film Critics’ Circle and

the National Society of Film Critics and corresponded occasionally

about projects involving those groups. I saw him often at

screenings and other events. He was always easygoing, witty and

curious. He was one of those rare people who could make everyone he

talked to feel important, just by making it clear that he was really

listening to them,. Even though personal qualities shouldn’t be at the forefront

of a career appreciation, which is what this mainly is, I mention them because they were reflected in Corliss’ writng, in every outlet he worked for. You got the sense that he

could get along with anyone while still being his own man and not

cutting the legs out from under anybody else, and that he could disagree

without being disagreeable. These are rare qualities, and they came through in his work. All of it.

I first discovered Corliss’ writing back in high school in Dallas, where I sometimes cut class and snuck off to the Dallas Public Library to pull old magazines and newspapers from their archives and read their film reviews. Over a series of weekends I worked my way through every issue of Time and Newsweek from about 1950 onward, to get a sense of how the publication’s critics viewed films that I loved or hated. (This was pre-Internet, remember; a lot of this stuff is now available through a mouse click.) Corliss’ stuff from the early eighties spoke to me more strongly than the work of any other critic for the weeklies, because it didn’t seem like the sort of thing that would run in a glossy weekly magazine. It reminded me of the kind of criticism I read in the local alternative newspaper (Dallas Observer, where I’d later become a staff writer) and in the film magazines that I dutifully read cover-to-cover while standing at the magazine rack at the bookstore, even though I hadn’t heard of most of the movies and they were likely never coming to Dallas. The writing was sharp and bouncy and surprising and filled with wordplay, some of which I wouldn’t discover until much later. He went right up to the edge of what was probably acceptable at Time, which had a house style and sometimes seemed to grind writers down until they matched it.

He acted as though every paragraph were a box of presents for the reader to open. He loved puzzles and word games and worked this fascination into his criticism. He gave away the “twist” in “The Crying Game” in sentences that did not reveal themselves as spoilers until after you’d seen the movie (“a man is never so naked as when he reveals his secret self”) as well as in a quietly audacious in-joke (read the first letter of each paragraph of the review). Time staff writer Richard Zoglin offers an even more impressive example in his obituary for Corliss: “Once, because of an arcane TIME rule, he was not allowed to append the

name of two correspondents at the end of a story he had written but they

had helped report. So he rewrote the entire story so that the first

letter of each paragraph spelled out the two uncredited reporters’

names.”

Also—and admittedly, this is shop talk—he was really good, perhaps better than any other critic, at writing what are called “reported think-pieces.” In this kind of piece, the writer has to work quotes, pertinent facts and sometimes figures into what is essentially criticism or analysis, and make the piece do double-duty as a work of personal expression and a reported article that gives basic information to the reader. (One of my editors used to call it a “two-fer,” because it was working in two modes at once.) This sort of piece can be hard to write if you care about preserving your personal style, because the two impulses, that of the critic and the reporter, can seem antithetical. But Corliss reconciled them time and time again, pun intended.

There was a marvelous period in the 90s and early aughts when he seemed to be everywhere at once. He was not just writing regular film criticism, he was also traveling throughout the United States reporting on various artistic, athletic, cultural and architectural subjects, including boxing, theme parks, and the transformation of Las Vegas.

The latter was such great example of how to infuse a reported piece with a spiky personal sensibility that I often recommend it to young writers. “The trick of being a great American city, at the end of this century of

electronic media, is to match muscle with myth, power with showbiz,” Corliss wrote in his cover story on Las Vegas. “You needn’t

gaze down from the revolving tower atop the Stratosphere hotel (where a

roller coaster winds around the spaceship-shaped aerie) to see that this

stretch of Nevada is pretty damn ugly: infinities, in every direction,

of dry, brownish-gray earth that is too bland to be called dirt, too

soiled to be called soil. The carcasses of extraterrestrials are

supposed to be housed at Area 51, the famously obscure military

installation nearby. But, really, why would aliens want to land here

anyway? Not for the scenic majesty. Just maybe, because Las Vegas is

near: for the love of the game. Vegas’ bounty and challenge is to be all

things to a certain kind of person: a childlike adult with too much

money, itching for risk and sensory overload. It’s not enough that the

New York-New York hotel evokes Manhattan’s skyline in its exterior

silhouette; it must have (of course) a Coney Island roller coaster one

floor above the casino. Visitors stand in line for an hour anticipating

their two-minute thrill, even as they stay all night at the craps table,

slouched over their ever-smaller pile of chips, still waiting for the

salvation of seven. Ambition and sensation are the twin signposts at the

last American frontier, and Vegas is their crossroads.”

I can’t even begin to tell you how inspiring this sort of Corliss piece was to me, as a

then-young critic who’d started out writing mostly film and video

criticism, but had grown up reading Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson and

Joan Didion as well, and wanted to be taken halfway seriously as a

reporter as well as somebody spouting opinions. One thing, maybe the only thing, that Corliss had in common with longtime New York Press film editor Godfrey Cheshire, a mentor to me, is that they both were undeniably reporters as well as critics, and the reporter part fed the critic part. You got the sense that they had arrived at their opinions after careful study of the facts at hand, be they the audiovisual facts of whatever happened to be on the screen that they were staring at, or the more tangible and verifiable facts gleaned through visiting places, reading documents, interviewing sources, or just sitting there sifting notes and looking for patterns (recurring phrases, images or situations) that might coalesce into an observation worth sharing.

A lot of people who write cultural criticism don’t do this. They appear to get the process ass-backwards. They write as if they started out knowing what they want to say, then shaped—sometimes omitted or warped—reality to “prove” whatever they already knew they were going to say. You never got the impression from reading Corliss that he worked that way, or thought that way. His eyes and ears were open. He was constantly feeding his brain with new data, new experiences, and poring over opinions he’d held previously and asking, “Was I right about this?” There was a sense that he was always learning, that he still thought of himself as a student no matter what age he was, and that it didn’t matter if he wasn’t an expert on a topic when he went off to report on it; that part of the experience of doing a cover story like the one on Las Vegas was learning new things and arriving at unforeseen conclusions.

Throughout my own career, which is heading into its third decade, there were many instances where I argued an editor into letting me write a long, reported piece on a subject other than film or TV by citing Richard Corliss’ cover stories for Time. “Do you think Richard Corliss was an expert on Las Vegas when he went out there?” That kind of thing. Likewise, there were moments where I’d be told by an editor that they didn’t have space for both a review and a reported feature or interview related to the thing I was reviewing, so I’d need to find a way to combine the two pieces into a “reported think-piece” or “critical feature” or something. I’d always grumble a bit and then think of Richard Corliss, who was a master at doing that kind of Frankenstein-hybrid piece while still making readers like me pore over every word and come away thinking, “Yes, that piece makes a clear, strong argument, and I also learned a lot from reading it, and only that writer could’ve pulled it off.”

Corliss gave me permission to do all kinds of things I wanted to do, and in some cases things that didn’t want to do, while feeling reasonably certain that I was always still me—that I hadn’t given anything up, that I knew how to make an assignment, any assignment, an expression of whatever personality I liked to think I possessed.

What a gift that was for a writer. I never thanked Richard Corliss for it. Now I wish I had.