I’m writing this review of the Roger Ebert biography “Life Itself” in a hospital waiting area, so that my typing won’t wake my dad. He’s sleeping in a room down the hall. He had a stroke on the Tuesday before “Life Itself” opened. I don’t want to get overconfident, because the tests aren’t all in yet, but he’s doing pretty well, all things considered, and the doctors seem to think a full recovery is possible.

Why did I just tell you that? Lots of reasons: First, Roger often worked personal details into his reviews. Second, a good chunk of “Life Itself,” a documentary inspired by Roger’s same-titled memoir, takes place in a hospital; director Steve James shows us graphic medical details that were previously hidden from public view, including shots of Roger, whose cancerous jaw was cut off in 2006, having his throat irrigated. Third, Roger was a professional father to me, as he was to a good many people, a fact that I’m more keenly aware of than usual at this moment, sitting on a couch under florescent lights, typing on a laptop at midnight.

Last but not least: when critics review films, they bring the sum of their intellectual capacity and life experience to bear, along with whatever drama (or comedy) they’re going through at that moment in time. “Life Itself” gets this. Life itself, that loaded two-word phrase, is what Roger really wrote about when he wrote about movies. Life itself is what I’m dealing with as I sit here in a hospital waiting room. And it’s what you’re dealing with as you sit here reading this review of “Life Itself.”

The movie is about cinema history and critical history, writing and reading, drinking and sobriety, religion and doubt, love and sex and marriage and parenthood and labor relations and so many other factors that combined to create Roger Ebert; and it’s about why, even if complete emotional detachment were an achievable goal for any critic of any medium (and I don’t think it is—only that some pretend it is), it’s impossible to achieve when writing about “Life Itself.” Roger was well-known to everyone who cared about cinema, and his work had a deep impact on all of them, including (perhaps especially) those who did not like or respect him and defined themselves against him. This review, written by the editor in-chief of the site Roger founded, is, to put it mildly, less detached than most. It may in fact be useless except as a measure of what the site itself “officially” thinks of “Life Itself.”

All that having been said, here we go:

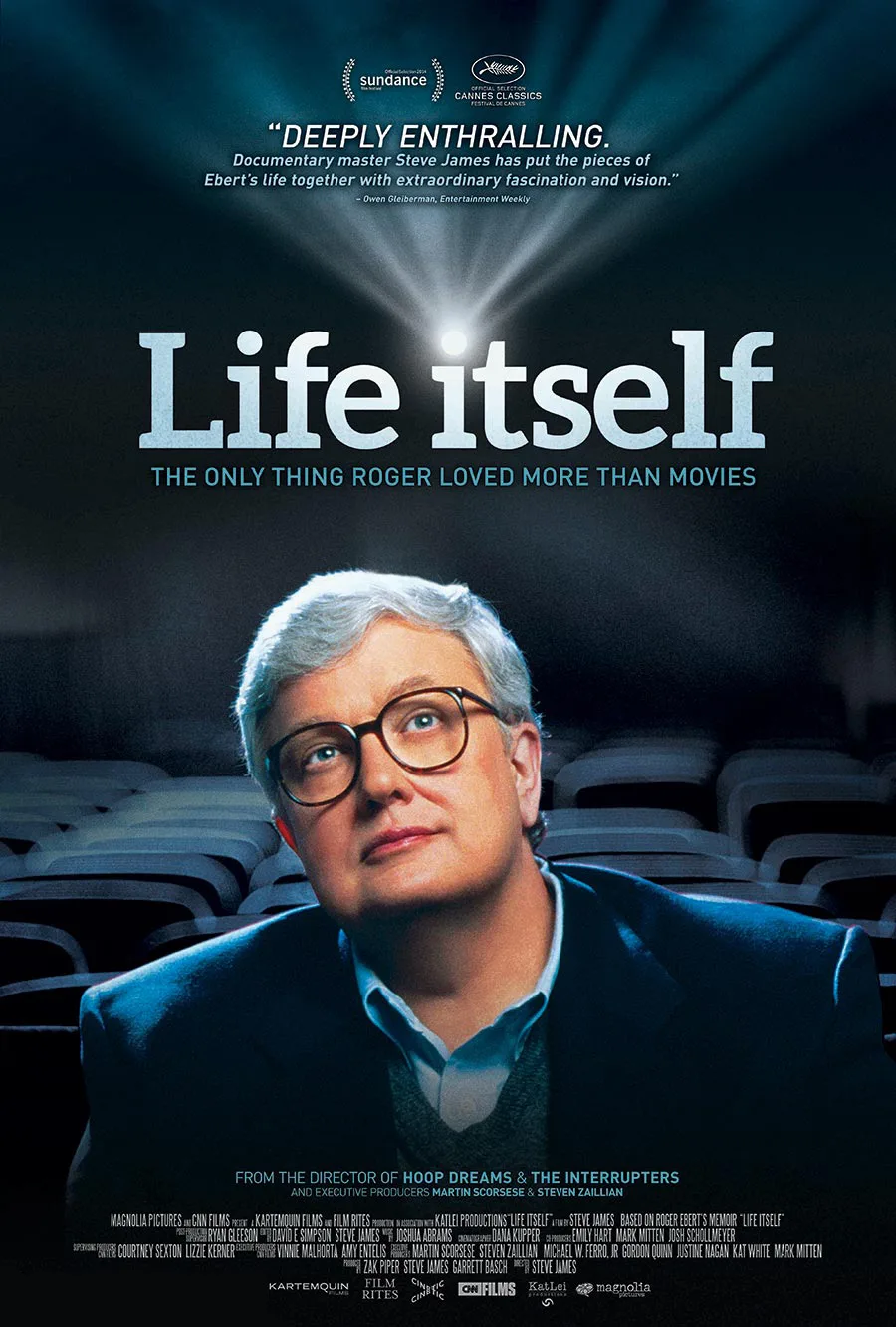

“Life Itself” seems like a very traditional nonfiction feature about a man’s life. It’s a mix of fly-on-the-wall documentary footage, talking head interviews, video and film clips, photos, newspaper clippings, and the like. It’s fundamentally an affectionate and sympathetic work, directed by a man whose breakthrough feature, “Hoop Dreams,” was basically made by Roger Ebert and his sparring partner Gene Siskel on their TV show back in 1994. It hits many of the high points of Roger Ebert’s biography, a good many of which were already enshrined in legend. We learn about Roger’s training as a student journalist at the University of Illinois, his alcoholism and sobriety, his friendship with famous filmmakers he wrote about (including Werner Herzog and Martin Scorsese), the development of his critical voice, and his innovative work in TV and on the Internet.

The opening section of “Life Itself” has a stunned, funereal tone. As James has explained in interviews, it was originally supposed to be an adaptation of Roger’s memoir, then morphed into something else when he died five months into production. But soon the movie relaxes and turns into a kind of filmic wake, with witnesses painting a full picture of the man, sharing stories of his virtues, flaws, blind spots and eccentricities. He loved to hold court. He liked to be the boss, the director of the film of his life. He could be gluttonous. He was a breast man who found nirvana through his association with exploitation filmmaker Russ Meyer. Early in his life, he could be brusque and arrogant and thoughtless. Later, he was gentle and sweet, and had a tendency to raise depressed people’s spirits by giving them unsolicited compliments and words of support.

The film chronicles two great love stories. One is between Roger and Chaz, whom Roger met in Alcoholics Anonymous and married in 1992 and is credited with changing him from a domineering, insecure and sometimes insensitive man capable of stealing a cab away from a pregnant woman (“He is a nice guy,” a friend tells James, “but he’s not that nice”) into the mellow, reflective, generous person celebrated in obituaries and appreciations. The other love story is a bromance between Roger and the hyper-competitive Chicago Tribune critic Gene Siskel, a print rival who became an on-camera debate partner and an off-camera business partner, then finally the brother that Roger, an only child, never had.

The present-tense framing device of Roger’s final stint in the hospital, having his throat irrigated to the tune of Steely Dan’s “Reeling in the Years,” eventually connects, cleverly and gracefully, with both the Roger-Chaz and Roger-Gene love stories. We learn that Gene died of a brain tumor before Roger had a chance to say goodbye to him, and that Roger, like most people in Gene’s orbit, wasn’t kept fully informed of his friend’s health struggles, and that he later told Chaz that if something like that ever happened to him, he would be as honest and transparent as possible, not just with his friends and family but with his readers. And he was.

The years following the removal of Roger’s jaw produced some of his best, most personal writing, because the disfigurement made him redefine the idea of a writer’s voice (after Roger lost his physical voice, his virtual or figurative one flowered), but also because his blog entries often dealt with the harsh physical realities of his life post-2006, and the emotional, philosophical and political musings that his health struggles provoked. Losing control of one’s body due to age or illness tends to spark a nostalgic impulse in writers. They sense time “slipping through our fingers,” as Roger once wrote, “like a long silk scarf,” and try to grab and hold it with words. The better writers harness the nostalgic impulse and turn it into an extension of criticism by other means, taking stock in themselves as they might take stock in an artist’s work.

Roger was one of the better writers. Many excerpts from his later work have a probing, curious quality. They are read aloud in “Life Itself”—sometimes by the computerized, Stephen Hawking-like voice emanating from Roger’s laptop, other times by voice-over performer Stephen Stanton, who captures Roger’s flat Illinois vowels and his plainspoken “Here I am on a soapbox” cadences—and form the intellectual and emotional heart of the movie.

“Life Itself” is less successful when it tries to examine what Roger stood for as a critic. It’s unabashed, as it should be, in its celebration of Roger (and Gene Siskel) as democratizing forces in film appreciation. It shows how they championed small movies and unknown directors (including Errol Morris and Gregory Nava) and inspired mainstream moviegoers to leave their comfort zones. But it falters when it recounts the Film Comment point-counterpoint between Roger and Time Magazine film critic Richard Corliss, who accused Siskel and Ebert of dumbing down criticism, and then again when it brings in former Chicago Reader critic Jonathan Rosenbaum to raise similar concerns. It seems to rebut them by pointing out all the careers they boosted, but it’s a rebuttal to complaints that Corliss and Rosenbaum weren’t exactly making. One gets the sense that Corliss and Rosenbaum are ivory-tower types making specious or wrongheaded and factually untrue gripes, when in fact they were making complex and admittedly messy arguments about what criticism should be, in print and on TV. This is a problem of filmmaking rhetoric, not bad faith—the movie respects Corliss and Rosenbaum, and shows that they respected Roger, too—but it’s still a problem.

“Life Itself” also errs, I think, in indulging a bit of Windy City defensiveness when it portrays Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael and other New York-based ’60s and ’70s critics as egghead types. Both in their hearts and in their prose, they were as direct and democratically-minded as Ebert. Every time I’ve seen “Life Itself,” Ebert pal Rick Kogan’s hilarious exclamation “Fuck Pauline Kael!” brings the house down, but anybody’s who’s read Kael knows there’s a wee bit of misrepresentation going on. A shot of Kael’s books on Roger’s shelf doesn’t communicate the depth of their kinship as smart populist film critics. I’d hate to think that people who first hear of Kael through “Life Itself” assume she was a Margaret Dumont type when she was more like one of the Marx brothers: an anarchic force in a line of work that was pretty reserved until people like her and Roger came along. (The two of them were among the only mainstream critics to recognize “Bonnie and Clyde” as a masterpiece during its initial theatrical run.) In the context of the film’s triumphs, these are quibbles. But they’re still worth debating, out of respect for Roger’s tendency to find flaws in other people’s arguments and tug at them to see if they’d unravel.

Again, nothing I have to say here is detached, much less objective. I love this movie. Everyone associated with this site seems to have enjoyed it, not just because it’s an essentially warm and loving work but because it has enough respect for Roger to refuse to turn him into a plaster saint. It’s about as emotional as a biography of a well-liked man can be without turning gooey.

Whenever I think of it, the first image that springs to mind is a bit from a TV interview conducted not long before Roger’s death, when Chaz loses her composure and instead of zooming in close to her tears, as a hack cameraperson might, it instead dips down to capture her hand and Roger’s intertwined. Life can be harsh, sometimes unimaginably painful, but we reach out. Roger described cinema as “a machine that generates empathy.” That’s “Life Itself.” It is an accessible, conventional nonfiction film, and yet at the same time it is wily and inventive, dodging and weaving to make easy labeling impossible, inspiring and engaging you, bending and breaking rules, inventing and reinventing itself as it goes along, much like Roger did. I watched it again in the waiting room before writing this review. I give it three-and-a-half stars. My dad gets four.