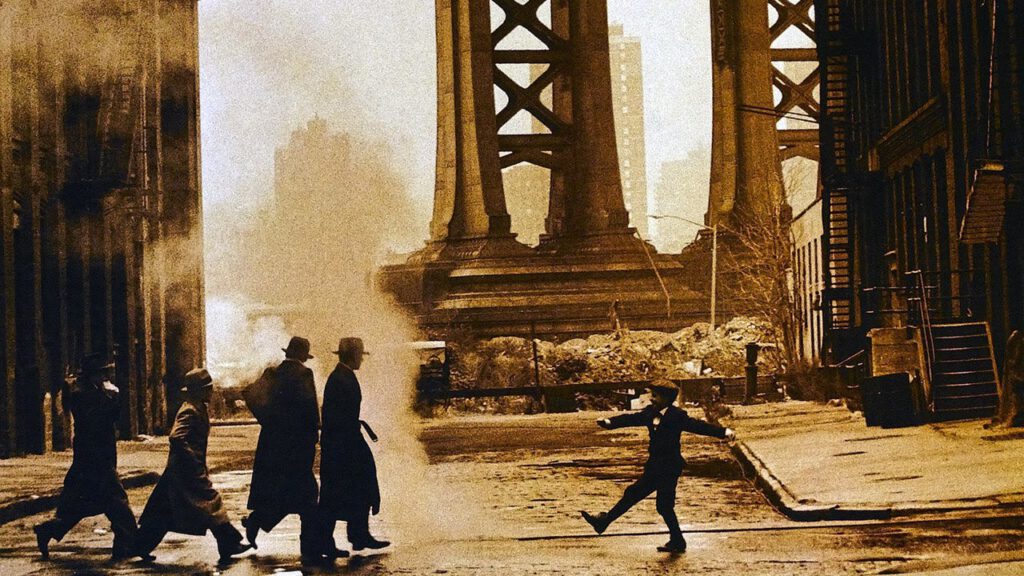

“Your part in ‘Once

Upon A Time In America’ isn’t that long, even in the restored version which

includes a crucial scene that clarifies your character’s part in the unusual

narrative tapestry, but as the saying goes, there are no small parts…”

“Only small salaries. And that was true in this case!”

Friendly, voluble Treat Williams broke into an infectious grin as he sat down

with me to talk about the restored version of 1984’s “Once Upon A Time In

America” in late September, as the movie was about to play at the New York Film

Festival and then see release in a comprehensive Blu-ray package (now in stores).

Williams’ role in the tapestry is that of labor organizer James Conway

O’Donnell, a feisty incorruptible force in the Prohibition era who morphs into

a sinister apparatchik for enigmatic forces in the movie’s 1969 “present.”

Williams was in town along with William Forsythe, who plays Cockeye, one of the

quartet of Jewish gangsters who make up the film’s focus—the other three are

played by James Hayden, who actually died before the film’s U.S. release, James

Woods, and of course Robert De Niro. To hear Williams and Forsythe tell it, the

making of the film was a dream come true, after which they continued with their

careers and saw from the sidelines the heartbreak that followed the production:

the death of Hayden in 1983 from a heroin overdose, the mutilation of the film

for U.S. distribution, which threw director Sergio Leone into an understandable

funk, and more. Looking back, both actors relished recalling the process

itself. “The greatest summer of my life,” Forsythe calls the shoot.

Williams was coming off of two dream jobs when he got the

call for “America”: working with Milos Forman on “Hair,” then Sidney Lumet for

the epic “Prince of the City.”

“I was on cloud nine. I had been given three great roles, one

after the other. And Sergio was very specific about who he wanted, because I

remember Mickey Rourke at the time being around and complaining ‘I can’t even

get a meeting!’”

The actor was hungry but hardly seasoned by this time. “John

Gielgud was once asked what’s good acting, and he said, it’s knowing what

you’re job is. That’s not something that I asked in those days. My main concern

was to be as real as possible,” Williams recalls of his approach when he got to

the “America” set. “I just let Sergio Leone guide me. I knew that I was basing

my character on Jimmy Hoffa to a certain extent. I wanted him to be incapable

of corruption at first. I did know this about the character, that as he aged,

money and corruption encroached. That was what I knew I had to do at first: the

squeaky-clean guy among these crooks.

“I have to tell you, that gasoline hose with which I’m being

doused as the young version of my character is introduced: that hose had been

very, very recently used…as a gasoline hose! As Cary Grant used to write in

sections of his scripts, ‘N.A.R.’ ‘No Acting Required.’ Oh my goodness. It was

just foul.”

Williams relished the relative luxury of the movie’s long

shoot. “I’m probably generalizing, but in my experience, back in that time, as

well, the European directors could be more generous in terms of allowing your performance to evolve. They had more money then. We weren’t shooting 18 days,

we were shooting four months. There was more time for an actor to play, and to

find it, and the director could relax a bit and think, ‘Well, he may not be on

track yet but he’ll get there.’ We did lots and lots of takes. Sergio, like

Milos Forman in ‘Hair, would wear us down. Bobby [De Niro] didn’t need to be

worn down. Sergio would speak through a translator, but beyond that it was

pretty straightforward.

“Bob De Niro was my absolute hero. Every young actor in New

York, there were two guys: De Niro and Al Pacino, who we hoped we could be half

as good as them one day. On set you never felt you were in a Bob De Niro film.

We were all actors in a Sergio Leone film. De Niro is one of the finest nicest

guys to work with when you’re just starting out. A really fine human being. He

gave me lessons in how to behave on a set. Bob’s attitude was, ‘Whatever you

wanna do, I’ll go with you. It’s gonna make the film better, do it.’ “

As for Leone, Williams recalled, “He loved every aspect of

making a film. I think that in this business there are directors and there are

filmmakers. Filmmakers have a vision. They know every aspect of the job. Sergio

was one of those. And that’s why it’s so gratifying to be part of the

restoration of his vision.” The new version, created in 2012, brings Leone’s

movie to a 212-minute running time, clarifies much of the byzantine plot, and

brings back Louise Fletcher, whose name appeared in the opening credits of the

U.S. version released in 1984, but who wasn’t seen in that version: a good

indication of how careless the butchering of that version was. “I wish we could

get a message to him saying ‘look what we did,’” Williams summed up.

For Forsythe, the role of brutal gang member Philip

“Cockeye” Stein took him from zero to sixty in his career. “It was really quite

a fascinating moment in my life. I had just started out. I had a small agent

who believed in me. And I got a phone call telling me, ‘You really gotta get

over to the Chateau Marmont right now,’ I went and I saw a casting director,

who looked me over and told me to prepare a monologue. I still didn’t know,

exactly, what they were looking for, or what the project was. I walked in ready

to go, with a monologue I’d prepared. And I see Martin Sheen walk out of one

room, which was a real ‘Wow’ moment. Then I heard someone else say ‘I can’t

believe I’m auditioning for a Sergio Leone movie starring Robert De Niro.’ And then, before that even sunk in, they

called me in. I did the monologue for video, and I used a choice in my

monologue: my grandfather, when he got mad, he did this little thing with his

eye—and it was sort of a cue to run, when I was a kid—I used that in the

monologue. I knew, at the end, that I’d done well, but given the nature of the

project and that people like Martin Sheen were auditioning, I didn’t think I’d

hear anything. But there was a call for me at my home when I returned, asking

me to come back. I came back. Sergio was sitting in a robe, looking like a

Roman god, and he just studied me. Just

looked me over, like every detail of myself was important. After a while he said, ‘In your monologue you

did something with your eye. In my movie there is a character named Cockeye.’

And then he paused for what seemed like an hour. And he said, ‘When I saw this

character, I always saw your face.’ And then he said ‘The part is 90 percent yours.’

The rest was to meet and be approved by Robert. So that was a gift from my grandfather.”

Like Williams, Forsythe was thrilled with the prospect of

working with De Niro. “For me it was

unbelievable. Robert was a great hero to me. When I saw ‘Mean Streets’ I had no

idea who Robert and Martin Scorsese were, and when I saw it, I was so moved I

went to the office of the theater and got a job as an usher. And I worked the entire run of the movie. So

it was overwhelming. All the actors. Working with Sergio, who was so kind but

also so rough. There was one actor, a guy you just couldn’t scare if you tried,

he had to show fear at a moment. Sergio had the prop guy hand him a tommy gun

and he screamed ‘Action’ and opened up the tommy gun. The actor was so startled.

The shot worked.”

I asked Forsythe how the four actors playing the gang led by

Max (Woods) got into a groove in syncing up their respective performing styles.

“There’s a still in which the four gang members are posing for a picture

holding champagne glasses. I was looking at that, just now, and each character

kind of is defined by the way he’s holding his glass. It’s so specific. And it

wasn’t something we talked about. Just the tilt of every glass is different. We

spent the time together, there was camaraderie, yes, but we were all working,

and helping each other. Robert was very

generous, as was James, and James Hayden was a very special actor, a special

actor, a special guy.” Hayden died of a drug overdose in November of 1983,

during a stage run of David Rabe’s “Tracks,” in which he was acting with Al

Pacino. “When the movie came out,

because James Hayden and I were just the rookies of the cast, our names weren’t

on the poster, although our faces were. So when the movie came out, every

poster I could find, I wrote James’ and my name on the posters. Mostly for

James.”

As for his own approach, Forsythe said, “Every character is

a color in the painting. I can only answer for myself: I wanted to know

everything I could know of the time. At a time when you couldn’t just punch it

up on Google! I read every newspaper I could get from that time period. I knew

the batting averages of the Yankees. To feel like I was in the middle of it.

And Sergio was demanding. After take 49 or 59, he might say, ‘Primo bono.’ A

great director takes the time. Today, sometimes I go to work with a director, I

take a look at their films and I think, ‘Oh my God, I’m gonna have to do all my

acting in three seconds!’ As demanding as Sergio was, everybody knew what it

was for. If Sergio said, ‘We are marching into hell to get this shot’ everyone

would have lined up. That level of commitment from everyone is really something

special. Which is why the mutilation of the U.S. release version was so

painful. All over the world, everyone embraced the movie because they’d

released a legitimate version. Everyone saw the art and mastery, and everywhere

I went in Europe I was treated like royalty. When the movie opened here in a

bastardized version, it broke his heart. They took the poetry out of it.” The

new version brings back the poetry, and so much more, and both actors clearly

could not be more thrilled.