There’s no end to the essays by baby-boomers recalling the golden age of art cinema from the ‘50s to the ‘70s, many of them proclaiming the death of the movies in the present day. I was born in 1972, so I missed out on personally experiencing this arthouse heyday; my earliest exposure to world cinema came in the late ‘80s, when its US distribution was at an unprecedented nadir. (Anyone who wants to complain that too many films are being released now in big cities should take a look back at how hard it was to see the vibrant Chinese and Iranian cinema of that period.) The ‘90s were my personal peak moment for world cinema, particularly the films of East Asia and the renaissance in France spearheaded by Claire Denis, Olivier Assayas and Arnaud Desplechin. Such films managed to say something new about urban life that resonated with this New Yorker without reducing themselves to the “we are all connected” pabulum popularized later by Paul Haggis and Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu. To a large extent, Asian directors like Wong Kar-wai and Takeshi Kitano aren’t working at their peak anymore, but filmmakers such as Wang Bing, Johnnie To, Hong Sang-soo, Jia Zhang-ke and Apichatpong Weerasethakul continue to make masterful work. Fellini, Truffaut, Bergman and Kurosawa were household names even with people who weren’t cinephiles; seeing “The Seventh Seal” and discussing it over cappuccino was a rite of passage for every culturally literate person in the ‘60s. (On the other hand, Andrew Sarris spent that time lamenting the brief runs of now-classic films like Carl Dreyer’s “Gertrud.”) The same can’t be said for something like Apichatpong’s surrealist reveries, even if they express something similarly mystical and operate on the same level of skill.

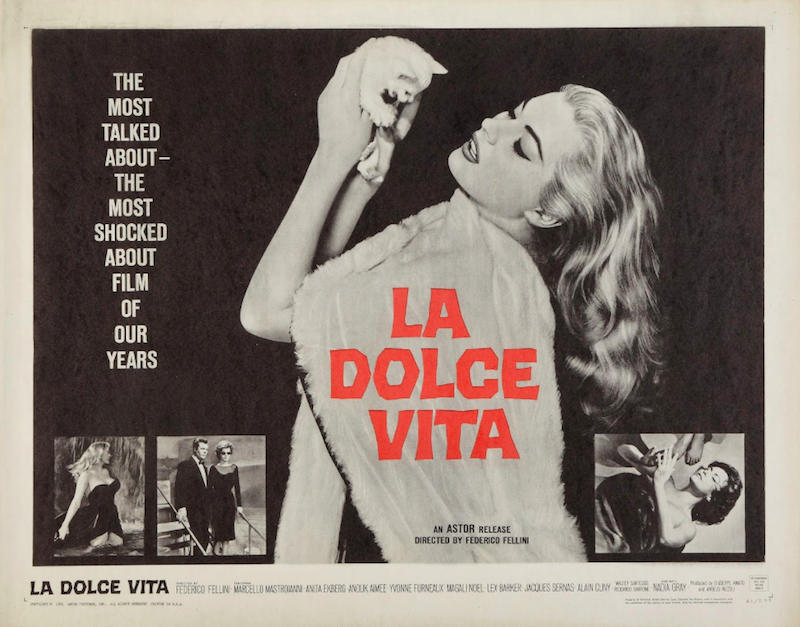

Box office analyst Tom Brueggemann, who writes two columns for the “Thompson on Hollywood” blog, agrees that the taste for foreign-language films was largely generational: “It was steady through the ‘50s and just exploded with ‘La Dolce Vita.’ ‘La Dolce Vita,’ although it often played in a dubbed version, had a domestic gross that would adjust in contemporary terms to more than 100 million dollars. There had been a domestic audience for Bergman films and other Italian films, but ‘La Dolce Vita’ really opened doors for Italian cinema and the French New Wave. I’m a massive fan of American studio film through the ‘70s, but the limitations on thematic material, because of censorship, and style made what got shown over here from Europe and other places a lot more interesting as an alternative.”

The Hong Kong cinema of the ‘80s and early ‘90s was the last “New Wave” that had an impact on mainstream American taste, in the diluted form of Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”—in unadjusted dollars, the most popular foreign-language film ever released in the US—and dubbed versions of Jackie Chan films, as well as its influence on Hollywood fare like the Wachowskis’ “The Matrix.” But the taste for Asian cinema that Generation X seemed to have didn’t get passed down to the next generation. In 2004, Zhang Yimou’s “Hero” grossed more than 50 million dollars and topped the U.S. box office for a week, despite the fact that it’s in Mandarin. Now it feels like a victory for Wilson Yip’s 2016 film “Ip Man 3” to gross more than two million dollars in American theaters.

You’d think there might be a cable channel devoted to foreign films, but the Sundance Channel and IFC have consistently dumbed themselves down instead of offering such an alternative. At the risk of making world cinema sound like kale salad, one of the most valuable services provided by foreign films is showing how Iranian liberals might view sexual politics—Jafar Panahi’s “Offside,” which depicts girls in male drag trying to attend a soccer game from which they’re barred, demonstrates that Iranian feminism is no oxymoron—or how the Chinese might respond to their country’s environmental degradation, even in a film as seemingly frivolous as Stephen Chow’s “The Mermaid.” That’s a perspective we don’t usually get from the news, which filters everything through an American perspective.

Brueggemann sees things differently. As he relates, “Now ‘The Amazing Race’ goes around the world to different cultures. You have live news from different places. To some extent, the interest in what isn’t American is satisfied more readily by other means. Now the stuff that’s different is different from films in its own country. Hou Hsiao-hsien is as different from most of Taiwanese cinema as he is from the rest of the world.” Singling out a particularly awful film that was a worldwide hit, he says, “‘The Intouchables’ is an example of a French version of an American movie, which may be one reason it was a success here.”

Brueggemann pointed out one more factor drawing audiences away from foreign-language films: the temptation of Hollywood and English as a lingua franca for commercially ambitious directors. As soon as Iñárritu had a taste of success, he headed north. Even a director like Michael Haneke, who made “Funny Games” as a polemical provocation against Hollywood depictions of violence, wound up remaking it in English, although all of his other films are in French or German. Only the most formally adventurous directors seem capable of resisting the siren song of the English language; Argentine filmmaker Lisandro Alonso’s casting American actor Viggo Mortensen in “Jauja” but having him speak only Danish and Spanish seems amazingly perverse in the current climate. Brueggemann describes the situation: “The ‘Taken’ films are French, but Americans think they’re made here. Take a director like Baltasar Kormákur, who made some good films in Iceland and then ‘2 Guns’ with Denzel Washington. Years ago, he would have stayed in Iceland.”

For a perspective on how one markets foreign-language films in such a forbidding climate, I turned to Richard Lorber, CEO of the distributor Kino Lorber. In the past year they’ve released Paul Verhoeven’s “Tricked” and Jia’s “Mountains May Depart,” as well as Chloé Zhao’s “Songs My Brother Taught Me,” a US film set on a Native American reservation. I asked him about the difficulties of releasing films by Jia, whom I consider to be mainland China’s best working director. He responded, “There are advantages when you’re working with an artist like Jia, who’s very contemporary and dealing with the issues of the day, with a philosophical and political slant on his commentary. So you still have a film with its longeurs and that’s challenging, and, for some tastes, disjointed. The expectations of seeing a Chinese film for more genre-oriented folk are not going to be satisfied. On the other hand, he has huge critical support, and the efforts we put into a theatrical release are going to be satisfied in other markets, whether it’s digital, home video or educational.”

Lorber went on to emphasize the importance of Best Foreign Language Film Oscar nominations for a director like Jia and a distributor like Kino Lorber. As he describes it, “We were disappointed that the first Jia film we released, ‘A Touch of Sin,’ and ‘Mountains May Depart’ weren’t chosen as China’s nomination for the foreign film Oscars. It was a blow to Jia. He told me he was bruised by the experience. It took some of the wind out of our sails in terms of what we thought we could accomplish. ‘Mountains May Depart’ played all the major festivals. At the end of its release, it will have played 35-40 markets. We’d like to think it will be established as one of the classics of tomorrow.”

When Miramax was at its peak, I often hated it, due to their habit of buying up films like Abbas Kiarostami’s “Through the Olive Trees” and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Pulse” and keeping them from release from years. (The former still hasn’t been released on home video.) Yet when they cared about a foreign-language film, they knew how to market it. Now that the Weinsteins no longer have access to Disney’s deep pockets, their interest in world cinema has vanished, although they had hits with “The Intouchables” and, to a lesser extent, Wong’s “The Grandmaster.” Other distributors have followed their lead, leaving the market more open to genuinely independent companies like Kino Lorber. Sony Pictures Classics is the one studio offshoot that still seems interested in foreign-language films, but even their attention is flagging, and they struggled to get László Nemes’ “Son of Saul” to earn a million dollars prior to its Oscar win. The kind of ambition that the Weinsteins had is gone from the market. Are foreign-language films now incapable of grossing 20-50 million dollars because no one puts serious money into marketing them, or does no one bother doing so because they’d be sure to lose their money? Will a director like Jia ever reach an audience in the U.S. beyond a small niche? I hope we don’t have to wait for another generational shift to get the answer.