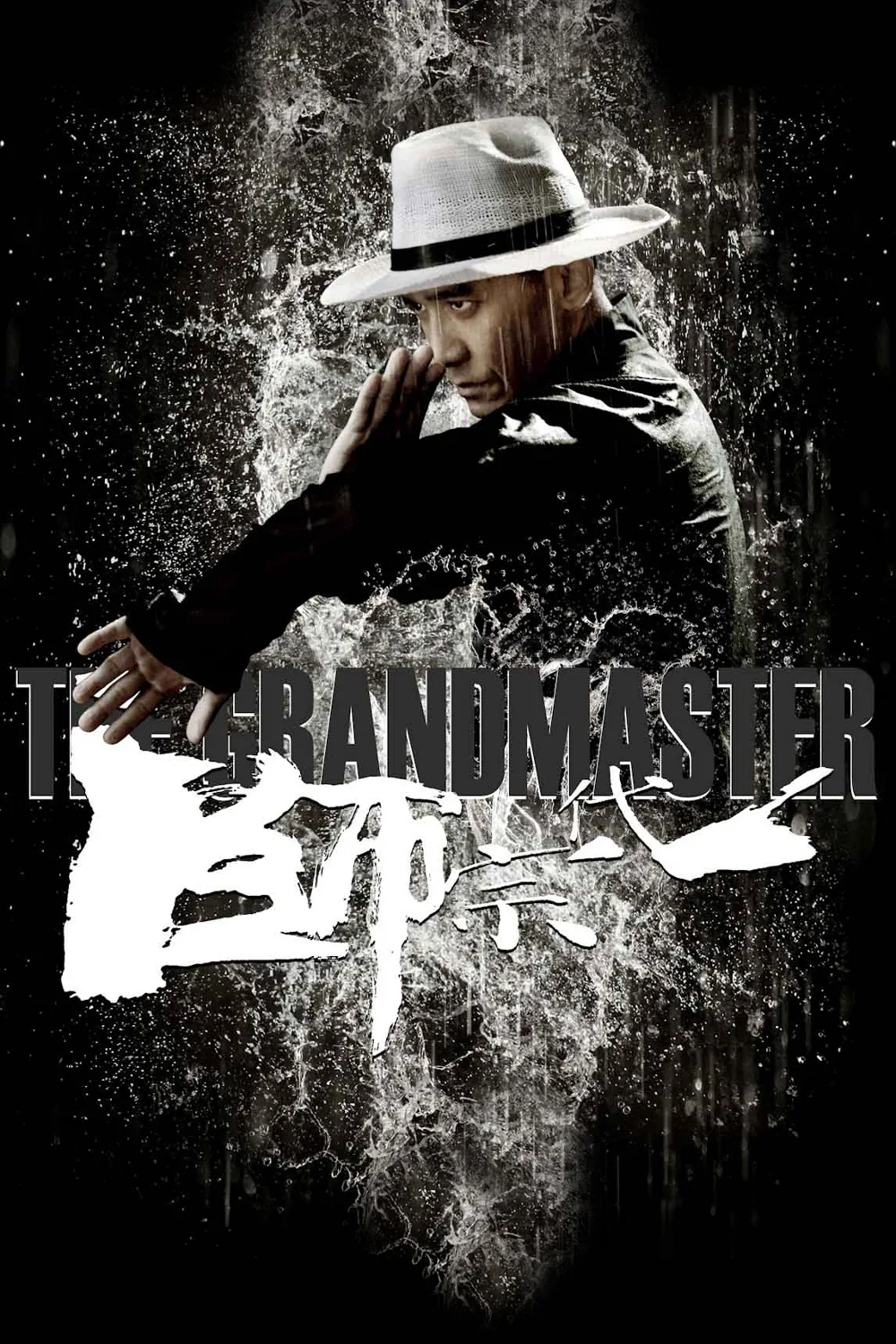

All of writer-director Wong Kar-Wai’s ten feature films star one seductive, maddening, tragically romantic lead actor: time. Every one of Wong’s main characters weathers an intense relationship with time. It’s often a brutal contest, monitored by such odd scorekeepers as a bucket of melting ice (“As Tears Go By”), the expiration date on a can of fruit (“Chungking Express“), a train depot clock (“Days of Being Wild”) and the steep stairwell leading to a noodle stand (“In the Mood for Love“).

Wong’s characters do their best to find some peace, clarity and happiness in this lifetime, which their creator rarely grants. Whenever he does, the screen lights up with surprise and delight. Yet the shadows are always close by, which makes the joys in his films as tense and gloomy underneath as the sorrows are brightened with oddball humor and loveliness. (I remember the desperately lonely character in Wong’s “Chungking Express” trying to cheer up his dripping laundry: “I told you not to cry. You must be strong”) All as the clock ticks away and the world turns, sometimes in delirious time-lapse.

“The Grandmaster” pits time against its first truly formidable foil, wisdom. The people in Wong’s films are often flailing, scrambling and ducking away from time’s ravages as they try to live and love, but in “The Grandmaster” they have a complement of disciplines called the martial arts to steady them. Various schools of kung fu teach characters how to maintain poise and balance in battles of every sort.

Tony Leung, who plays the legendary wing chun master Ip Man (whose students included Bruce Lee), stands rooted like a tree. He never makes an extraneous move, never wastes words on empty ceremony or sentiment. The other master martial artists in the film are the same way: trees that bend and sway in the storm and could even be cut down but are almost impossible to uproot. “The Grandmaster” is a drunken love letter to experience, which helps us survive, and wisdom, which helps us face aging, loss and, ultimately, the abyss. Wong, who was called the coolest director in the world when he was much younger, is now 57. This film is about a man like him, who has proven himself in the world and enters mid-life exuding a new, sage kind of cool.

It’s evident in his close-ups, which often frame his actors as if they were national monuments. That might sound staid, but in context, the effect is as electrifying as any of the celebrated high-speed, slo-mo, super-saturated images of Wong’s youth.

I haven’t seen the 130-minute Hong Kong cut of “The Grandmaster” or the fabled four-hour rough cut but I do sense that the 108 minute version entering American theaters is a mere trailer for something grander and deeper. The film I saw moves, but often as if prodded along, reality television/cop-show style. This artificial propulsion hits several speed bumps of explanatory inter-titles that I suspect were inserted just to avoid including corresponding scenes that ate up running time.

It feels like an insult to American audiences. At this point, the self-fulfilling prophecy that Americans are too dim, antsy and self-absorbed to sit still for meditative films has almost become international law. Filmmakers now agree with the market research department that most filmgoers here, only a couple of generations away from “The Godfather” and presently committed to long-form, subtly complex television like “Breaking Bad,” somehow won’t accept a film steeped in genre if it isn’t paced like “Smurfs 2.” How much of this received wisdom is simply disinformation from bottom-line corporate executives who hastily interpret box office data to justify lazy, fast-buck attempts at guaranteed blockbusters? It’s the same industrious ignorance that says Third World audiences prefer graphic violence and crude humor, as if those were the only universal emotions.

I go off on this seeming tangent because, as much as time, “The Grandmaster” is about the respect an artist merits and the ways in which times of war and economic upheaval erode that respect. The Wushu masters, god-like figures before the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), become struggling teachers and performers during the Japanese occupation. In Hong Kong, scores of martial arts schools sprout up, and Ip Man goes looking for work where no one has heard of him. These new schools prize technical mastery and fierce competition over the philosophical, spiritual aspects of kung fu. Folks are in a rush to turn a fast buck, a reality which Ip Man accepts with the same grace and pragmatism with which he braved the horrors of war. Smiling bemusedly, he refuses to hustle up a living by demonstrating wing chun in carnival-like street exhibitions. He adapts to changing times but not to the prerogatives of fools with far more greed than vision.

One of the losers to time is Gong Er (Zhang Ziyi), a female fighter with whom the married Ip Man appears to have a possibly chaste but intense soul-mate love affair. She is stubbornly committed to the old ways passed down from her father, the grandmaster whom Ip Man has replaced. The irony is that the old ways have also kept her genius in the shadows, where all women were kept. She is the tree that gets cut down, and, in playing Gong with an aristocratic hubris that would embarrass Don Corbera in “The Leopard,” Zhang Ziyi finally becomes the Marlene Dietrich to Wong’s Joseph von Sternberg—if Dietrich could fight with the ferocity of Bruce Lee. Her showdown with fatally unwise challenger Ma San (Zhang Jin) and her too-late confession of love to Ip Man stand as two of the most deliriously lyrical scenes of Wong’s career.

Ip Man triumphs in his struggle with time—not through battle but by shrewd diplomacy: He trades his former status in a lost world for the privilege of teaching new generations the tried and true arts. It’s a glorious sentiment that, in the American version, plays as a mere footnote. So why do I give it three stars? Well, a glorified trailer by Wong Kar Wai is still something to see. The fight scenes, devised by Wong and grandmaster choreographer Yuen Wo Ping are majestic dances and, at times, philosophical conversations. As with the comic book cult of “The Dark Knight“, fans of Chinese martial arts films might appreciate this deeper reading into what many dismiss as a juvenile obsession. By all accounts, Wong arrived at this cut voluntarily, happily, but it plays like a concession to the clock of America’s homogenizing blockbuster industrial complex. There are so many scenes of explosive beauty that slip away just as we are falling headlong into the groove.