Back in the ‘70s, Rainer Werner Fassbinder described a number of his films as comprising the basis of a projected “moral history of modern Germany” (unfortunately he didn’t live to complete it). A number of works by Taiwan’s Hou Hsiao-hsien seem to be dedicated to a similar project. In mainland China, the one major filmmaker with kindred ambitions is Jia Zhang-ke. While stalwarts of Chinese cinema’s “Fifth Generation” such as Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige (as well as Hou in Taiwan) have deviated into making internationally crowd-pleasing, martial arts spectaculars, Jia has kept his eyes closely fixed on Chinese society as it has evolved through a tumultuous period of history.

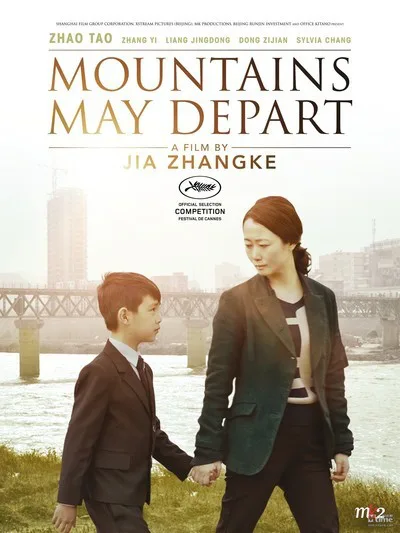

The most lauded of China’s Sixth Generation filmmakers, Jia has always evinced a confidence and a seriousness of purpose that are on fine display in “Mountains May Depart,” another intimate journey through history that’s as stirring and beautifully nuanced as anything he’s made. Though perhaps the greatest of recent Chinese films, it does, however, have a significant drawback that must be acknowledged at the outset.

The film’s story moves its characters through three different time periods, from 1999 to 2014 and then 2025. The first two transpire in China and center on a character played by Jia’s muse (and wife) Zhao Tao, whose performance is truly brilliant and the film’s emotional linchpin. The third part, which takes place mainly in Australia, finds Zhao’s character not entirely absent but sidelined to the point that the movie inevitably suffers.

As its time frame might suggest, the thematic center of the new film is the destabilizing impact of market-driven prosperity on China from the ‘90s till now. Set, as many earlier Jia films are, in the director’s hometown of Fenyang, in northern China, the story’s first part (which is also the longest) starts with the nation celebrating the approach of the year 2000. It’s a happy, celebratory time, due not just to the chronological landmark but also the newfound wealth and relative freedoms that have transformed China.

When we first see vivacious Shen Tao (Zhao), she’s in millennial party mode, leading a young dance troupe in an infectious routine set to the Pet Shop Boys’ version of “Go West” (Jia’s witty use of international pop music remains a trademark). But the abundance that much of China is enjoying has a problematic romantic corollary for Tao, who’s being pursued by two men. The roughly handsome, taciturn Liangzi (Liang Jin Dong), a mine worker, never really confesses his feelings but they are obvious enough. His rival, Zhang Jiansheng (Zhang Yi), on the other hand, is a glad-handing nouveau-capitalist who’s constantly offering gifts and other demonstrations of his affection.

This rich-man/poor-man sentimental dichotomy may sound all too schematic in its symbolism, but it works due to the humanistic detail Jia gives it and the sharp work of the main actors. Although Tao does fall for Zhang—who buys the mine where Liangzi works and fires him—we never feel that it’s solely due to the material comforts he offers her, even in a China that still remembers the astringencies of the Cultural Revolution. The young woman’s heart is mercurial and Zhang also promises the gift that arrives soon after their glitzy wedding: a son, whom the beaming father confidently names Dollar.

When the second episode arrives, much has changed. Tao is rich but long separated from Zhang, who lives with another woman and Dollar in Shanghai but has his ever-entrepreneurial eyes now set on Australia. In this section, Tao retains some of her buoyancy but her youthful optimism is tested and tempered by challenges on several fronts: her beloved father’s decline due to age; Liangzi’s return to Fenyang suffering from a lung ailment due to his work in the mines; and the estrangement she finds in Dollar when he comes for a visit.

In the story’s final part, we’re in Australia, where Zhang is wealthy but indolent, bitter and alienated from Dollar (now Dong Zijan), who doesn’t know what he wants, besides not wanting his dad’s life, and who falls into a desultory affair with an older female teacher (the redoubtable Sylvia Chang). On paper, this turn in the story no doubt makes good sense. The subject of Chinese people who’ve been propelled overseas by prosperity is a great one, and right in line with the chronicles Jia has provided till now. Unfortunately, this section of the film proves to be its weakest part, in part because Jia doesn’t seem entirely comfortable working in English, but more because the film lacks the powerful emotional focus provided by Tao and the actress playing her.

Always a playful stylist, Jia and cinematographer Yu Lik-wai give each section a different aspect ratio and incorporate other visual indicators of the different eras represented. There are also spurts of the surrealistic touches the director sometimes embeds in a realistic style that appreciates the particularities of landscapes and cities as well as the occasional disruptions and absurdities provided by post-Communist modernity. Whatever Jia shows us and wherever he takes us, we’re always aware of being in the hands of one of the contemporary world’s great filmmakers.