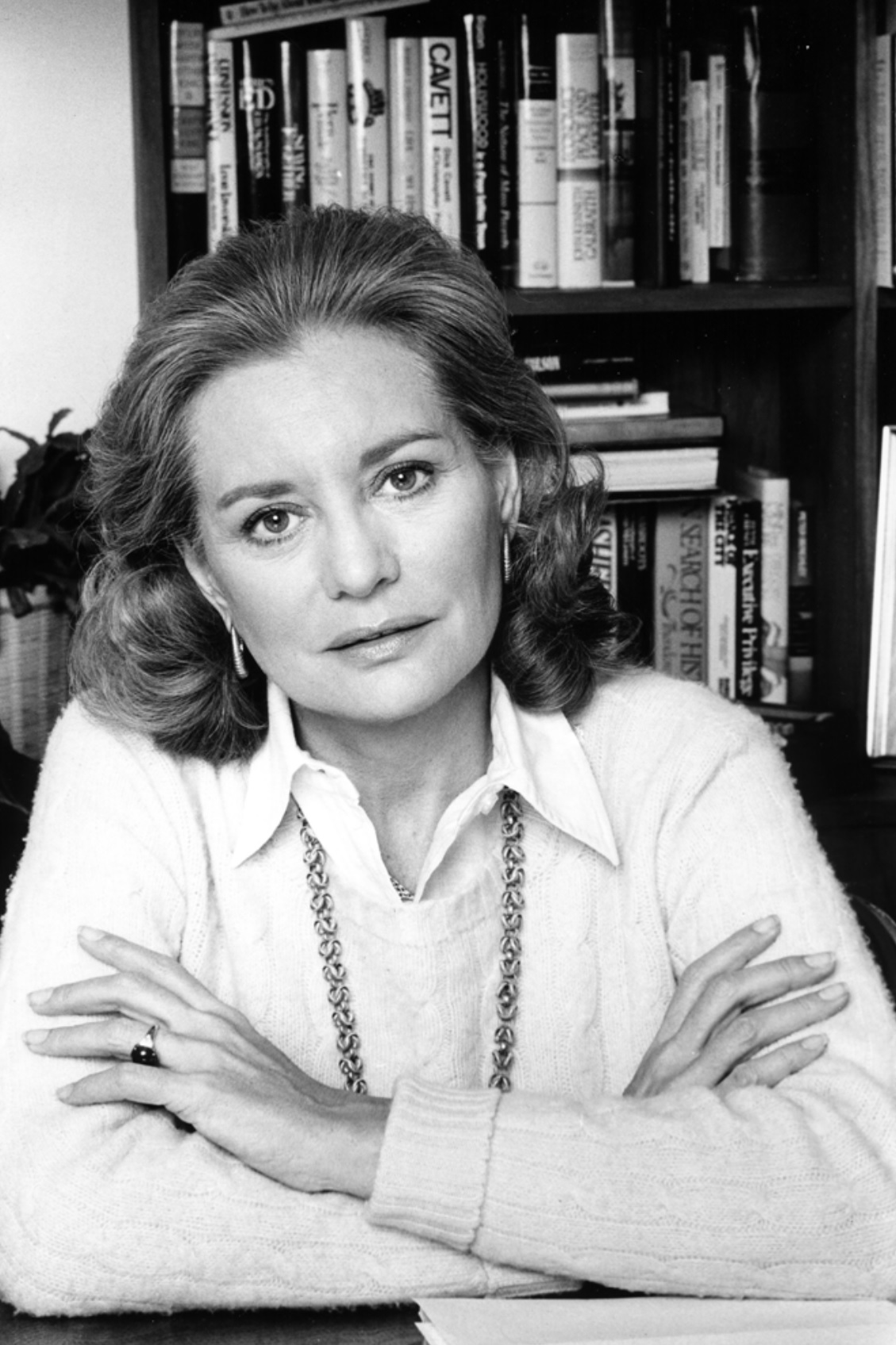

Those of us of a certain age grew up with Barbara Walters. I don’t just mean we watched her from the time we were little girls to the time we raised children of our own. I mean that as we got older, we saw her go from the “Today Girl” on “The Today Show,” relegated to the weather and light-hearted “women’s topics” like cooking and fashion, to pioneering positions as a network nightly news anchor, the creator of the daytime powerhouse talk show “The View,” and the premiere interviewer of politicians, world leaders, and celebrities over decades. Seeing her did not just show us what we could be; she showed us how to be it. Whether our own aspirations were to follow in her footsteps as a broadcast journalist or to follow our own dreams, she showed us that determination and a commitment to excellence could make someone unstoppable. She also showed us how to respond to public failures without fear or shame. There was enormous publicity about her becoming the first woman to co-anchor a nightly news show, then the most prestigious spot in broadcast journalism, and a lot of comments about the size of her pay. And there was even more publicity about the animosity from her co-anchor, Harry Reasoner, and the truncated tenure of her role. But what had been a side project, her prime-time specials, were enormously popular, and they led to a new direction. Her end of year “Most Fascinating People” shows were an annual tradition.

Barbara Walters grew up in the glamorous-adjacent world of Lou Walters, the man she described in her memoir as “my brilliant and mercurial impresario of a father.” Lou Walters was an agent going back to the days of vaudeville, the son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants who came to the United States at age 15. His clients included the radio star Fred Allen and “The Wizard of Oz” tin man, Jack Haley. So, his daughter was always comfortable around celebrities.

Lou Walters made and lost several fortunes as the economics of the country in general and show business in particular shifted. Jackie, Barbara’s only sister, was cognitively impaired. This instability and knowing that she would always be responsible for her sister bolstered her resolve to succeed in an era when it was unusual and widely frowned upon for women to want to have the kind of careers usually reserved for men. She described herself as “a sad and serious little girl.”

She initially planned to call her memoir, Sister, because of the impact Jackie had on her life, and because in the memoir she was for the first time open about her conflicted feelings of love, shame, and responsibility. But she ultimately called it Audition, seemingly an odd choice for someone with an astonishing record of achievement. It is an indication of what impelled her. She never felt that she had arrived, that she was done. “Much of the need I had to prove myself, to achieve, to provide, to protect, can be traced to my feelings about Jackie….As I look back,” she wrote, “it feels to me that my life has been one long audition—an attempt to make a difference and be accepted.” Tellingly, she named her only daughter Jacqueline, after her sister.

Barbara referred to her “Today Girls” predecessors as “tea-pourers,” whose “major requirement on the Today show was to look wide awake and pretty at 7:00 am … In that ‘don’t worry your pretty little head’ era the popular culture on television mirrored the sweet and subservient image of the good wife; it did not include women who were doing anything with their brains.” She was the one who changed that, in part, she acknowledged, because she came along at the right time.

But she helped to make it the right time. When her co-host, Frank McGee, refused to allow her to ask questions of interview subjects, finally agreeing that after he asked four, she could ask one, she came up with a way around it. His rule applied only to interviews in the studio. If she found her own interview subjects and filmed them outside the studio, she could do it any way she wanted. Those interviews took audiences into the subjects’ homes and workplaces. After McGee’s death, she finally became the official co-host, leading to women co-hosts on every morning show. She considered that one of her most significant legacies.

She is credited with pioneering the “get” interview, and she talked to the biggest names on the planet, including every President in office during her career as well as notorious killers (the Menendez brothers, former private school headmistress Jean Harris, Mark David Chapman, who murdered John Lennon), pop singers from members of the Beatles to Diana Ross, Dolly Parton, Barbara Streisand, Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga, Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Elton John, and Jennifer Hudson, movie superstars like Gloria Swanson, Clint Eastwood, Julia Roberts, Liam Neeson, Richard Gere, Bette Davis, and Sean Connery (she correctly predicted on camera that he would hear some criticism for his comment that it was acceptable to slap a woman). Yes, she did ask Katharine Hepburn what kind of tree she would be, but only after Hepburn herself said she felt like a tree (the answer was oak, by the way).

She interviewed world leaders Fidel Castro, then-Prince Charles, and the Shah of Iran. She asked Vladimir Putin if he had ever ordered anyone killed. He gave her a long, hard look before he said, “Nyet.” She interviewed Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat – together, their first time speaking to one another. She asked Richard Nixon if he was sorry he didn’t burn the tapes (he said yes). She asked Monica Lewinsky if she ever told Bill Clinton she loved him and what he said when she did (he said, “That means a lot to me”). She told the Kardashians they had no talent (they didn’t argue). She wore bunny ears and a fluffy tail to see what it was like to be a Playboy bunny (noting on air, “I’m not a bunny; I’m a reporter for the National Broadcasting Company”).

She was endearingly good-humored about the people who made fun of her, like Gilda Radner’s “Baba Wawa” and Cheri Oteri’s impression of her breathless “20/20.” She even had Oteri interview her – as her – in her farewell to “The View”. When she presented the Tony Award for best revival, she joked that she was selected because everyone thought she had seen the original productions, like “La Boheme” in 1896. I met her once when I was in college at her alma mater, Sarah Lawrence. My dad was being interviewed on The Today Show and I was waiting for him in the green room. She made a point of coming in to say hello. She was warm and gracious and asked me about what was happening at the school, which now has a beautiful student center named for her.

Her 1970 book, How to Talk to Anyone About Practically Anything is still an exceptionally practical – and revealing – guide to what made her so good at getting people to confide in her, those who were very experienced at cultivating a highly polished public persona and those who were still in a state of shock after being unexpectedly thrust into the public eye. She gives advice about the most difficult and stressful situations, talking to people who are grieving or in crisis or upset. She described what she did when a man she was interviewing live used the n-word on the air (she waited until it was over and then apologized to the audience). She gives readers suggestions for making a bore less boring (ask provocative questions). She mentioned that babies often enjoy seeing adults shake their keys (she points out that the title does say “anyone”).

Barbara Walters did endless research on her subjects and was delighted when they would respond, “How did you know that?” She was the best when it came to provocative questions. She liked to ask, “What is the biggest misconception about you?” (Diana Ross said, “That I am a bitch.”) “Do you have a philosophy by which you live? (Arnold Schwarzenegger said, “Stay hungry.”) “Finish this sentence for me. [Name of celebrity] is …” (Mariah Carey said, “A nice girl.”)

The key, though, is in her interview with the Archive of American Television, where she explains that is not about the questions she worked for hours to prepare. What matters is responding to the answer. “It’s not the first question; it’s the follow-up. You have to listen.”

Photo credit: Lynn Gilbert