Think back to high school for a second, before you watch—or rewatch—Steven Soderbergh’s deceptively spare “sex, lies, & videotape,” now out on DVD and Blu-ray from Criterion. In high school, you learn about the different kinds of irony. There’s verbal irony, in which what is said is different than what is meant. There’s situational irony, in which one character knows something another character doesn’t. And there’s dramatic irony, in which the audience knows something characters don’t know. It’s this last quality that’s most crucial to “sex, lies, & videotape”—it’s the whole story. And the most important tool for telling this story is, quite simply, time.

The spare plot of the film is an old story, one you’ve probably heard a million times. Mysterious outsider blows into town, causes a lot of trouble, and everyone’s life is changed. In this case, the mysterious outsider is Graham, played here by a young and mischievous-looking James Spader. He’s staying with John, a college buddy, played by the never-creepier Peter Gallagher, and his repressed wife Ann, played by Andie MacDowell with a powerful mood of shedding shyness.

The trouble he stirs up is twofold: he turns on the last-call light for John’s affair with his wife’s sister Cynthia (an indelible Laura San Giacomo), and he does so by…well…doing what he does, which is filming women talking about their sexual experiences. No one can handle his presence, and the world we see at the end of the film is the opposite of the world we see at the beginning. And what makes the progress of the film so devilishly seductive is the way in which Soderbergh both respects and does not respect the unities of time, both as it is managed in more traditional narratives and as one would think it would be managed to push this particular story forward.

Over and over, we have a-ha moments when watching this film. A moment when Ann is talking to her therapist about resenting her husband’s invitation of an old friend to visit is followed not soon after by Graham’s arrival at the house—but not before we see a scene of her husband and her sister in bed. Another infidelity scene is spliced directly with a scene in which Ann and Graham go house hunting (at John’s urging). You continually watch and realize these events are taking place without the characters’ mutual witness, at relatively the same time, with no split screen—and gradually that feeling of slight surprise turns into something else.

You might also, when you were in high school, have discussed how different kinds of irony are supposed to make you feel. Verbal irony is supposed to give you a quasi-humorous twinge; situational irony is supposed to give you a mild sense of dread; and dramatic irony is supposed to make you feel smarter than the characters but also, in a sense, smarter than yourself. Smarter than a mere narrative, able to see broader paradigms, themes, ideas that rise above the permutations in the story. But what does that mean for a story like this, about a man who screws with an old friend’s relationships but has none of his own? What does this over-knowing have to do with time? And beyond that, what’s the significance of this relationship for Soderbergh’s future work?

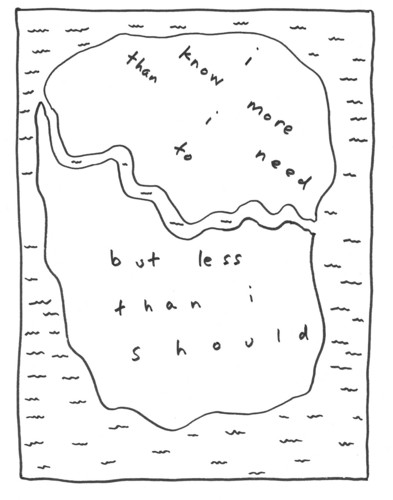

The answer to all of these questions lies, in differing degrees, in the way Soderbergh fills in the framework of this, his offhandedly daunting debut. The plot is moved forward here by conversations, chiefly, and they’re not necessarily laden ones. They contain reminiscences: John ribs Graham about college sexual misdeeds; John and Cynthia have pillow talk about their relationship; Ann talks about her repressions, her fears, and her suspicions with her therapist. Conversations of this sort, verging on the incidental or the all-too-personalized, would kill other films. Here, given that Soderbergh is presenting the story to us in a way that that clicks along the way life clicks along, we watch with increased attention and experience the conversations as if we were having them, almost as if we had had them already. We know more than the characters know, we know that they are lost, but we also feel we are lost with them.

There’s also the videotapes to consider, occupying as they do a third of the title. The videotapes are accurate chroniclers of time which become a means of escaping it. Graham isn’t using the tapes as part of a larger project, though he does allude to it; the purpose of the tapes is for him to watch them, and ultimately masturbate to them, because he’s unable to feel sexual pleasure any other way. Of that activity there isn’t much to be said, although it’s curious that Soderbergh chose it as a cornerstone for the film, given that there are three things most would consider true about it: it’s uncommon for anyone to complain about how long It takes; some people are able to spend hours doing it, in endless delay of completion; and a widely accepted cliché for its desired goal is to say that “time stopped.”

The film is a portrait in miniature of the rest of Soderbergh’s work, in which time pressure lurks, sometimes making itself obvious, sometimes not, but always present, popping up when you least expect it. Take a film like “Out of Sight,” for instance. The film jumps back and forth in time plenty, which is somewhat unremarkable, but there is one scene, the famous scene in a trunk, in which escaped convict Jack Foley (George Clooney) and agent Karen Cisco (Jennifer Lopez) get to know each other during a prison getaway, in which Soderbergh plays with real time. It’s significant that Cisco has just, literally before arriving at the prison where Foley is escaping, met with her father, who gives her a gun for her birthday and chides her about dating a married man; it’s also significant that, probably at the same time that Cisco was eating with her father, Foley and his associates were busting out of jail. It’s significant that the two things take place at roughly the same time because then the paths of the two characters come together neatly, almost like a mathematical equation: cop with bad judgment and a new gun, meet handsome criminal; fail to stop getaway, end up in car trunk.

And the rest of the film bears out the degree to which their lives and personalities are wholly separate in some senses and parallel in others. Again, we’re smarter than the characters, and somewhat smarter than the story, and so the spectatorship becomes that of the viewer watching himself or herself watch a film, slowly developing a take on it. Or take “Mosaic,” Soderbergh’s much ballyhooed online multi-path narrative, in which the viewer has the option of choosing a storyline. The pleasure is not so much in the story one chooses as in the curiosity about what story one could have chosen, that some other user, possibly across the world, is watching at the same time. You become smarter than yourself as you watch Soderbergh’s films.

I give you full permission to watch as many of the supplements as you wish. The interview with a young Spader is interesting for the signs it shows of his affable non-commitment, a quality which will harden later. The three-person documentary featuring Gallagher, San Giacomo and MacDowell brings home to what extent the actors internalized and understood the characters they were playing, be that from a political, post-Reagan perspective as in Gallagher’s case, or from a physical, sensual perspective, as in San Giacomo’s case, or from the perspective of someone who knows and understands specifically southern women, as in MacDowell’s case. The director’s commentary with Neil Labute is also important, though problematic in a film in which silence is so important.

Of the most interest, and to be watched if you watch none of the other extras, is Soderbergh’s introduction to the DVD, in which he refers, tellingly, to the way in which the film represents an arrival at a turning point on each character’s life timeline: “There was me before this happened and there was me after this happened, but none of them know this is coming,” the this being the entrance of Graham into their lives. He then talks about the “math of the movie,” in which the movie shapes itself as an equation in which each character is a variable in the equation—something which he wasn’t entirely conscious of at the time but is definitely conscious of now, and which is certainly floating through his current work. It would have to be, for Soderbergh to be the quintessential ironist that he is. You’re not watching characters move through time and space when you watch this film; you’re watching them being arranged in such a way that you notice their movement through time and space, and can comment on it. And the noticing you do is so intense, and so absorbing, that you may in fact start to notice yourself, moving through space and time in the same way.