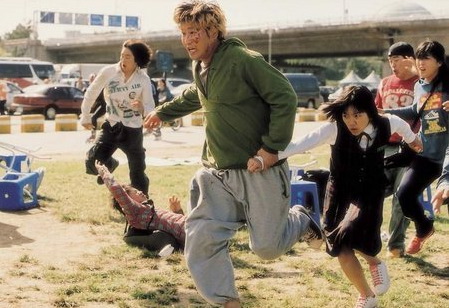

TORONTO — “The Host” (2007) (or “Gue-mool,” which sounds better) is a South Korean monster movie in which a mutant amphibious creature swims beneath the Han River, scampers among the girders beneath its bridges, prowls its sewers, and occasionally leaps onto its banks to grab some human souvenirs. The creature is just doing whatever it’s bred — or mutated — to do, but the monsters who created it, and who mischaracterize the nature of the threat, thereby making the thing practically impossible to catch or contain, are Americans — portrayed as the world’s most aggressive exporter of bureaucratic incompetence and misinformation.

In the first scene, set in 2000, a U.S. military official in scrubs (Scott Wilson — setting the funny/horrific tone for the entire movie) directs a reticent Korean subordinate to empty potently toxic chemicals into the Han. After all, it’s a big river. By the end of the film, a Senate investigating committee finds that the U.S. bungled the whole thing, and then compounded the damage by covering it up. Imagine.

Of course, the lives affected by this particular imperialistic hysteria aren’t Americans, but Koreans — in particular, the comically fractured Park family whose patriarch runs a riverside refreshment stand. On the political as well as the horror/science-fiction level, this time it’s personal. The marvelous creature (part squid, part gecko, part salamander, part sandworm, part vagina dentata, created by San Francisco’s The Orphanage), snatches the youngest Park (a uniformed schoolgirl of 13), and the rest of the clan reunites to avenge her.

Director Bong Joon-ho shifts tones with quicksilver dexterity, cannily keeping the audience (and the film) just on the edge of losing its balance and splashing into the Han. Humor turns to horror and back again in a flash, while generic requirements are both fulfilled and cleverly overturned. Even the pathos works, because it’s a little bit cock-eyed. How does the movie do all this? Must be something in the water…

Born out of a suicide (a friend of the filmmaker’s) and an attempted suicide (the filmmaker’s own), “2:37” is a movie 20-year-old Australian Murali K. Thalluri never intended to write or direct. It just came out that way.

“2:37” is a suicide whodunnit. In the course of one day at school, multiple character perspectives, and a maze of Steadicam shots that virtually trace those in Gus Van Sant‘s “Elephant,” we catch glimpses from the lives of several kids, any one of whom could turn out to the one in a puddle of blood on a restroom floor at 2:37 in the afternoon. (I wonder if the title isn’t also a reference to Kubrick’s Room 237 in “The Shining,” another film drawn with a Steadicam.)

Though they appear to attend a big school, each of these kids feels utterly — at times disconsolately — alone. Even when they’re surrounded by friends, the bonhomie is forced, superficial. Hey, it’s high school. (As a friend said after the screening: “I guess it just shows that Australian high school is as f—ed up as American high school.”) Emotions — big emotions — pass through like storms on any spring day. And that’s part of what Thalluri is getting at: There’s a whole catalog of After School Special subjects here (sex, drugs, other physiological and psychological problems) but any one of them, even the most trivial, could be the trigger for a suicide attempt.

The film flows naturally around its central contrivance, employing unforced performances by unprofessional actors and a visual style that uses available light to pull you into the worlds these students inhabit. The black-and-white reality-show style interviews with the kids are unnecessary, and the movie will no doubt be be met with charges of “derivative!” when compared unfavorably to Van Sant’s masterpiece. But, even if I hadn’t read the press notes (after the screening), I’d still admire the authenticity and unerring behavioral observations of “2:37.”

(Side note: “2:37” was a 2006 Cannes Film Festival selection; “Elephant” won the Palme d’Or and the Prix de la mise en scène in 2003.)

Here’s the way my festival began: I was returning to my hotel room after dinner, around 8:30 Wednesday, the night before screenings began for the 2006 Toronto International Film Festival. It was almost dark and the streets and sidewalks were crowded, everything lit up with the ambient glow of store signs and an advertising jumbotron looming over the major intersection of Bloor and Yonge Streets. A pair of police officers were standing in the street, directing traffic to clear the way for some motorcycle cops who rode through with their blue and red lights flashing. Farther down Bloor, more sirens and lights were approaching. The vehicles wailed as they turned, heading south on Yonge, followed by hearse after hearse after hearse after hearse.

“It’s the soldiers,” somebody said. Heads nodded. The cops in the street saluted as the limos made the curve. People on all four corners stood silently — not stiffly or formally, but attentively, while the significance of the black parade soaked in. The procession passed and the two cops climbed on their motorcycles and rode on. The light changed, and we were on our own again, so we walked.

Welcome to Canada.