(or, Who put the mise in the mise en scène?)

UPDATE: Here’s a new, more color-accurate frame grab — an unmodified screen capture from the new-ish Blu-ray set of the “Alien Anthology.”

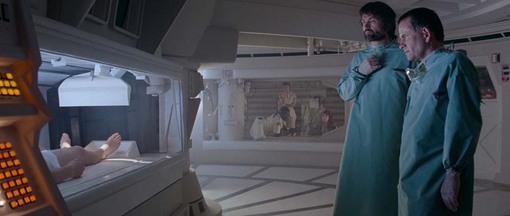

Look at the frame-grab above from Ridley Scott’s “Alien” (1979). I’m not making any high claims for it as a masterpiece of composition, or saying that it has great meaning in the context of the movie, or that it expresses anything typical/archetypal about Scott’s style or values (aesthetic, moral). But it sure is a pleasure to take in. You’ve got the interplay between the right, left and center, the foreground and the background, each in its own space, but visually interrelated. The camera is in the operating room with Dallas and Ash, who are looking at their comatose patient, Kane, whose feet are at left, in a quarantine chamber (because he has a xenomorph hugging his face). In the background, through the window, is the rest of the Nostromo crew, anxiously waiting for news. That’s right — the entire (human) cast of the movie in one shot.

We can hear what the crew is saying as well as what Dallas and Ash are saying (exactly what they’re saying is not terribly important, just their worry and uncertainty), though it’s not clear if they can all hear one another. The drama is expressed visually: Kane is immobilized, isolated, beyond reach; Dallas and Ash are the intermediaries between his living death (in quarantine) and life, as represented by the rest of the crew, but they don’t know what to do; the crew is on the outside looking in, twice removed from Kane who was, until just a short time ago, one of them.

I accidentally rediscovered this image last week while doing research for my profusely illustrated post on the Alien films, “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “Prometheus,” and I can’t get it out of my head. Scott is often guilty of directing department store windows rather than movies (without the resonance of, say, Wes Anderson or Stanley Kubrick), but the design, camerawork and direction of “Alien” (not to mention the loose, Hawksian/Altmanesque improvisational style of the performances) cohere into something extraordinary.

This shot is a beautiful example of the antithesis to what I have labeled “one-thing-at-a-time filmmaking.” The basic composition (roughly symmetrical with an opening in the center) is repeated throughout the movie, as befits a movie about violation, penetration and passages of birth and death. It also gives your eye places to wander, details to soak in. It allows you room to breathe. Throughout, “Alien” gives you ample opportunity to look around and admire the industrial/organic design of the Nostromo, and it entices you to notice nooks and crannies where threats might be lurking. (At the end, the alien actually melds and intertwines with the escape pod’s ductwork.)

I’m told that the French term mise en scène literally translates as “setting of the scene,” or “putting on stage,” or just “staging,” for short. In film classes, I recall we used it to mean something more like “the arrangement of elements within the frame,” distinguishing it from “montage,” which was the temporal arrangement of shots in a scene or sequence. It evoked everything that was happening in the frame, moment by moment: the set, the actors, the movement of the camera, the depth of field, the lighting, the sets… everything.

In his famous essay “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Andrew Sarris addressed this concept of “interior meaning” as

the ultimate glory of the cinema as an art. Interior meaning is extrapolated from the tension between a director’s personality and his material. This conception of interior meaning comes close to what Astruc defines as mise en scène, but not quite. It is not quite the vision of the world a director projects nor quite his attitude toward life. It is ambiguous, in any literary sense, because part of it is imbedded in the stuff of the cinema and cannot be rendered in noncinematic terms. Truffaut has called it the temperature of the director on the set, and that is a close approximation of its professional aspect. Dare I come out and say what I think it to be is an élan of the soul?

Again, I’m not saying I think this particular shot speaks to Sir Ridley’s directorial soul. But it says everything about the soul of movies themselves, and what distinguishes a richly cinematic sensibility from a pedestrian one, the multi-layered from the simplistic, the resonant from the superficial, the poetic from the prosaic. The old saw has it that movies are about showing, not telling; images like this can make a movie sing instead of merely signifying.

Below is the original screen grab I used for this post — off of Netflix on my MacBook Pro, with Photoshop Elements “Auto Smart Fix”: