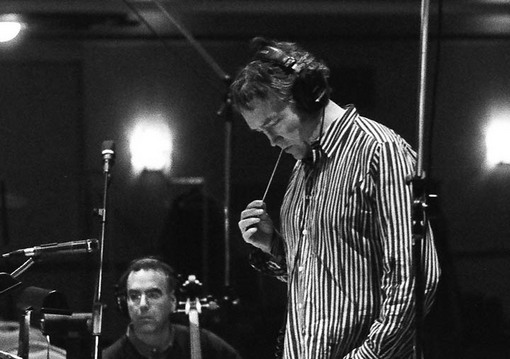

(Photo by Dean Parker)

“Carter Burwell‘s score, drawing from themes from American folk music of the era, is one of his greatest.”

— Glenn Kenny, review of “True Grit” (2010) on MSN Movies

1.

I had missed the news, quietly announced in late December, that Carter Burwell’s score for the Coens’ “True Grit” (which includes Mahleresque orchestrations based on the traditional hymn, “Leaning on the Everlasting Arm”) and Clint Mansell’s Tchaikovsky-influenced music for “Black Swan” (of course he’s going to interpolate “Swan Lake” into the score — that’s the challenge!) would not be eligible for consideration in the Oscars’ Best Original Score category. But the category is for score, not Best Original Tune. The presence of a hymn melody or passages from a famous ballet are key to what these compositions set out to accomplish, and how they are integrated into their respective movies. Those things shouldn’t be held against them.

Orchestral composers have worked with folk music and other melodic sources for centuries. Mahler used “Frehre Jacques” in his first symphony and other traditional Jewish and folk tunes are found throughout his works. (For that matter, the melody — and even part of the arrangement — for TV’s “Star Trek” theme is right there in Mahler’s Seventh!) And Tchaikovsky — jeeez, the 1812 Overture is just the French and Russian national anthems. But the composer fragmented them, wove them together and otherwise re-composed them into one of his most famous pieces.

(Besides, we’ve known for months that Hans Zimmer’s score for “Inception” — which is nominated — is built on a slowed-down, sampled and otherwise manipulated recording of Edith Piaf singing “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien.” That’s using an existing tune in a movie score, too, isn’t it? Seems to me that all of the above are legitimate compositional techniques.)

Is Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Rhapsody on a Theme of Pagannini” a lesser composition simply because the variations take as their starting point part of a melody by another composer? What does the Academy make of the symphonies and orchestral settings of Charles Ives, who constructed them from well-known American folk music? Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Britten, Dvořák, Shostakovich… so many great composers turned to traditional tunes for inspiration.

This is not to say that somebody should be able to take a chunk of, say, Ives’ Fourth Symphony, slap it onto a soundtrack, and claim it as an “original score.” But, yes, music from Tchaikovsky’s ballet is indeed used in “Black Swan” (like, for instance, when there’s ballet dancing going on). But consider what “customer reviewer” Jon Broxton writes in his assessment of the original soundtrack recording at Amazon.com:

Cues such as “Mother Me”, “A Room of Her Own” and “Cruel Mistress” invoke the clear stylistics of Tchaikovsky’s writing, especially in the woodwinds and pianos, without making many direct references to the great Russian’s melodies. One of the most impressive things about Mansell’s work in cues such as these is the way he implies the `ghost of Tchaikovsky’ everywhere in the score, almost making it follow Nina around, haunting her, messing with her head, throughout the course of the film. She can’t escape from the pressure of the performance, of the music, of her mother’s vicariousness. It never leaves her alone.

Sounds like a terrific concept for a psychological horror movie score to me.

2.

The other thing about Carter Burwell is this little anecdote I found on his web site:

I fell into this business more or less by accident. Skip Lievsay, who was sound editor for the film Blood Simple, knew my music from the New York club scene, and suggested I meet with the Coens about scoring the film. I saw a reel, recorded a few sketches, and after months of interviewing other composers they hired me. I basically expanded those original sketches and did my best to synchnronize them to the film by playing to a stopwatch. After it was released I got more calls, for instance from Tony Perkins who was directing Psycho III. I never intended to pursue this work, but I love film and I love music, so I’m really quite lucky to be doing this.

So, my favorite sound designer and favorite film composer are old friends! No wonder they were able to collaborate so closely on one of the most daring scores in movie history — the almost subliminal soundtrack to “No Country for Old Men” (2007), in which the score is the sound design and vice-versa. (By the way, the other bold score of that year — Jonny Greenwood’s seething score for “There Will Be Blood,” a deliberately obtrusive approach at the other end of the spectrum from what Burwell and Livesay were doing — was disqualified because “scores diluted by the use of tracked themes or other preexisting music, diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer shall not be eligible.” Greenwood had taken some of his cues from an earlier piece he’d written for the BBC, “Popcorn Superhet Receiver.”)

And I love “Psycho III” — the movie and the score — too.

Top of page: Photograph of Carter Burwell scoring “True Grit” by Dean Parker, from Burwell’s web site, The Body.