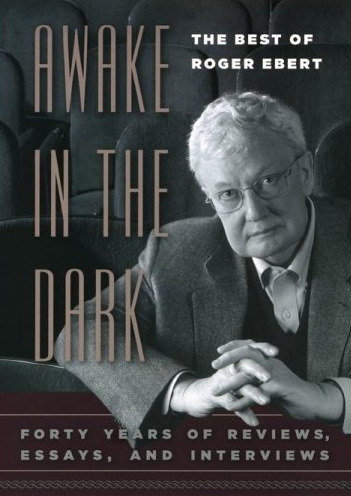

“Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert,” just published by the University of Chicago Press, achieves a first. Though the Sun-Times film critic remains the dean of American cineastes, his essential writings have never been collected in a single volume until now. “Awake in the Dark” surveys his 40-year catalog, including reviews, essays and interviews. The following is an excerpt from the book’s introduction, and for the next five weeks we’ll publish excerpts here from the collection’s highlights in each decade, from the ’60s to the ’00s.

I began my work as a film critic in 1967. I had not thought to be a film critic, and indeed had few firm career plans apart from vague notions that I might someday be a political columnist or a professor of English.

Robert Zonka, who was named the paper’s feature editor the same day I was hired at the Chicago Sun-Times, became one of the best friends of a lifetime. One day in March 1967, he called me into a conference room, told me that Eleanor Keen, the paper’s movie critic, was retiring, and that I was the new critic. I walked away in elation and disbelief, yet hardly suspected that this day would set the course for the rest of my life.

How long could you be a movie critic, anyway? I had copies of Pauline Kael’s “I Lost It at the Movies,” Arthur Knight’s “The Liveliest Art,” and Andrew Sarris’ “Interviews With Film Directors,” and I read them cover to cover and plunged into the business of reviewing movies.

In my very first review I was already jaded, observing of “Galia,” an obscure French film, that it “opens and closes with arty shots of the ocean, mother of us all, but in between it’s pretty clear that what is washing ashore is the French New Wave.” My pose in those days was one of superiority to the movies, although just when I had the exact angle of condescension calculated, a movie would open that disarmed my defenses and left me ecstatic and joyful.

Two movies in those first years were crucial to me: “Bonnie and Clyde,” and “2001: A Space Odyssey.” I called both of them masterpieces when the critical tides were running against them, and about “2001” I was not only right but early, writing my review after a Los Angeles preview during which Rock Hudson walked out of the Pantages Theatre, complaining audibly, “Will somebody tell me what the hell this movie is about?” My review appeared the same day as the official world premiere in Washington, D.C.

CRASH COURSES

Back then, the Clark Theater in the Loop showed daily double features, 23 hours a day, seven days a week, and was run by Bruce Trinz and his assistant Jim Agnew. They told me I had to see certain films — not those by Orson Welles, Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock, whom I knew about, but those by Phil Karlson, Val Lewton, Rouben Mamoulian, Jean Vigo and all the others. Through them, I met Herschell Gordon Lewis, the director of “Blood Feast,” “The Gore Gore Girls,” “Two Thousand Maniacs!” and 34 other titles. In later years, when Lewis became a cult figure, I was asked for my memories of him, but I never saw one of his movies or discussed it with him. Instead, in the living room of the boardinghouse in Uptown where Agnew lived with his family, I sat with Agnew, Nash, Lewis, a film booker and publicist named John West, and Lewis’ cinematographer, an Iranian named Alex Ameripoor, and we looked at 16mm movies on a bedsheet hung upon a wall.

They felt an urgency to educate me. We saw “My Darling Clementine,” “Bride of Frankenstein” and “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” with Nash dancing with James Cagney in front of the screen and telling me Cagney’s secret was always to stand on tiptoe, so there would seem to be an eagerness about his characters, as opposed to the others. When John Ford died, Agnew and Ameripoor and some others from this group drove to Los Angeles and stood at his grave and sang “Shall We Gather at the River,” and drove back to Illinois again. Although Herschell Gordon Lewis was notorious as the director of violent and blood-drenched exploitation films, I remember only a thoughtful lover of the movies.

FRIENDS AND FESTIVALS

These years had amounted to the education of a film critic. I went to film festivals. At New York in 1967, I met Pauline Kael and Werner Herzog and many others, but to meet those two was of lifelong importance. Kael became a close friend whose telephone calls often began with “Roger, honey, no, no, no,” before she would explain why I was not only wrong but likely to do harm. Herzog by his example gave me a model for the film artist: fearless, driven by his subjects, indifferent to commercial considerations, trusting his audience to follow him anywhere. In the 38 years since I saw my first Herzog film, after an outpouring of some 50 features and documentaries, he has never created a single film that is compromised, shameful, made for pragmatic reasons or uninteresting. Even his failures are spectacular.

I went to Cannes. There were only five or six American journalists covering it at that time. The most famous was Rex Reed, then at the height of his fame, and I remember that he was friendly and helpful and not snobbish toward an obscure Chicagoan. Andrew Sarris and Molly Haskell were there, Richard and Mary Corliss from Time, Charles Chaplin from the Los Angeles Times, Kathleen Carroll from the New York Daily News, George Anthony from Toronto and the legendary Alexander Walker from London.

WATCHING THE MASTERS

I visited many movie sets. In those days there were no ethical qualms about the studio paying the way, and I flew off to Sweden to watch Bergman and Bo Widerberg at work, to Rome for Fellini and Franco Zeffirelli, to England for John Boorman and Sir Carol Reed, to Hollywood for Billy Wilder, Henry Hathaway, Otto Preminger, Norman Jewison, John Huston, countless others, most memorably Robert Altman, who struck me as a man whose work and life amounted to the same thing. Those were the days before publicists kept their clients on a short leash and reduced “interviews” to five-minute sound bites.

I walked with Zeffirelli and Nino Rota in the garden beneath Juliet’s balcony while the composer hummed the movie’s theme to the director. On assignment from Esquire, I spent a day with Lee Marvin in his Malibu Beach house, days with Groucho Marx, Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum. The Marvin interview is my personal favorite. If you read it, consider that he liked it, too.