• Toronto Report #1

I walk out the hotel door and don’t know where I am. I’ve spent almost ten months in Toronto, one film festival at a time, and I know my way around. So where am I? The concierge says the district is “near the Entertainment District.”

Not far away are some of the big Toronto legit houses. Turn a corner and I realize I’m near both Queen and King, two great streets for walking. And towering over everything is the new Bell Lightbox, the new high-rise home of the Toronto Film Festival.

The Reitman family, which includes Ivan and Jason, kicked off the Lightbox with a cool $22 million. Toronto developer John Daniels, who essentially underwrote TIFF in its earliest years, built the Lightbox and was a supporter. Among the many other donors was the late Toronto film critic Brian Linehan, in for a million. Those Torontonians. My far-flung correspondent Grace Wang has been inside the Lightbox and loves its theaters, public areas and festival offices. She has the intriguing title of Social Media Coordinator for the festival. When TIFF was founded, Social Media did not exist, and neither did Grace. I say we’re seeing progress.

I haven’t been to the Lightbox yet. Werner Herzog and Errol Morris will hold a discussion there Monday, and I’ll be angling for the front row. In the meantime, all of our festival has taken place at the Scotiabank Cineplex, which replaces the familiar Varsity Cinemas as the venue for most of the press screenings. It’s much larger and offers many more seats, which is just as well, because the press corps here is second only to Cannes. This is now a big, brawny film festival, one of the Big Three, or is it Four, and the unofficial starting line for Oscar season.

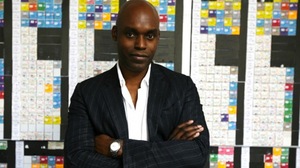

Cameron Bailey and the schedule

Yes, but the true value of TIFF comes in its support for expert, passionate programmers and passionate volunteer screeners, who seem to consider almost every available film from everywhere for the final cut of merely 400 entries. I’ve been following the Tweets of fest director Cameron Bailey as he jetted from Europe to Africa to India, China, Japan, looking at movies. Then there was the jigsaw puzzle of finding times and theaters for everything. He says it’s like simultaneously holding 400 birthday parties.

Some of the festival films were previewed in Chicago, New York and LA. Some played under the radar at Telluride. A lot played at Cannes. Wherever they came from, they go out from this time and place to bring nurture to a continent of movie lovers starving after the usually cheerless summer drought.

A few early examples, alphabetically:

Buried. (Rodrigo Cortés, Spain). One set, one actor, two props: A cell phone and a lighter. The universal nightmare: Being buried alive. Paul Conroy (Ryan Reynolds) has been taken hostage in Iraq and awakens in a coffin. His captors have apparently left the phone and the lighter in aid of their plan to hold him for ransom. He starts telephoning for help, and has infuriating experiences with a 911 operator, the Pentagon switchboard, and the private contractor he drives a truck for.

I knew the premise going in, and wondered if the film would be boring. Not at all. I fell into easy identification with the plot, having been marked for life by a childhood horror comic (adapted from a book?) about a millionaire so terrified of being entombed that he has a bell on his grave with a cord that can be pulled from in his coffin. But then, wouldn’t you just know, something goes wrong.

The budget for “Buried” is said to be $3 million. In one sense, low. In another sense, more than adequate for everything director Cortés wants to accomplish, including his special effects and the voice talents of all the people on the other end of the line. Ryan Reynolds has limited space to work in, and body language more or less preordained by the coffin, but he makes the character convincing if necessarily limited. The running time, 95 minutes, feels about right. The use of 2:35 wide screen paradoxically increases the effect of claustrophobia.

Never Let Me Go. (Mark Romanek, UK). I found Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2005 novel completely absorbing and probably difficult to film. The novel doesn’t depend on a big surprise reveal at the end, but unfolds its secrets through a point of view that assumes everything is already known. In its alternative present, human beings are cloned to supply body parts. They’re raised for this purpose, and after three, sometimes four, donations, they Complete. They’re not intended to live full lives. They live within a social structure which encourages the full acceptance of their purpose of Donors.

Ishiguro’s method is to accept that world as a given. His novel is about the meaning of human identity. Are cloned humans persons, or are they simply organisms for the supply of body parts? That’s what the novel is about, in the intensely personal terms of the organ donors themselves. There are three central characters, Kathy (Carey Mulligan), Tommy (Andrew Garfield) and Ruth (Keira Knightley). All are cloned. All accept their donor roles. But all have feelings.

The way Mark Romanek (“One Hour Photo“) approaches this material is rather unexpected in terms of the possibilities in this story for sensationalism. He and his writer, Alex Garland, treat it with respect. They seek Ishiguro’s melancholy tone. That’s inescapable — unless they had turned it into a thriller about a revolt. As in the book, the film’s moral questions center on whether the clones have a soul. Form your own opinion. Mine is that to the degree any human has one, all must have one.

Tabloid (Errol Morris, U.S.) is one of the damnedest films ever made by this artist as documentarian. He presents his “favorite protagonist,” Joyce McKinney, who in 1977 was involved in the infamous “Case of the Manacled Mormon.” She was alleged to have kidnapped an American Mormon missionary in the UK, handcuffing him to a bed, and making him a sex slave. In the British tabloid version of the story she became sexually obsessed with him about a relationship.

The case exploded into a tabloid war at the time, occupying many front pages. It had been all but forgotten when McKinney surfaced again in recent years after finding a South Korean scientist to clone her dog. Morris gains full access to McKinney, then a somewhat shady nude model, now a poised and persuasive 60-something, who proclaims full innocence and has an explanation for everything. As if often the case with Morris, we can never be sure what he thinks, only that he wants to baffle us with the impenetrable strangeness of reality.

The Scotiabank Escalator of Terror: Scarier than a horror film

“Rashomon” will inevitably be evoked in discussions of this film. Morris presents lawmen with boundless reasons to think McKinney guilty of stalking, abduction and possible rape. He also allows McKinney to offer a perky alternative perspective on the same events. Her alleged victim is portrayed in murky ambiguity; once unshackled, he prudently has refused all interviews. As often, Morris surrounds his story with unexpected asides, blindsides us with surprise revelations, and weaves in an ominously urging score by John Kusiak.

Errol Morris makes intensely personal films, which are neither about his subjects nor himself, but about the intensity of his gaze. No wonder he invented the Interrotron, which allows Morris and the person he is speaking with to peer directly into each other’s eyes. He, and we, are constantly asking what we think of this person–and what’s really going on here? If “Tabloid” is a love story, it is one only Errol Morris could film.

☑ Recent entries in my blog, Roger Ebert’s Journal.