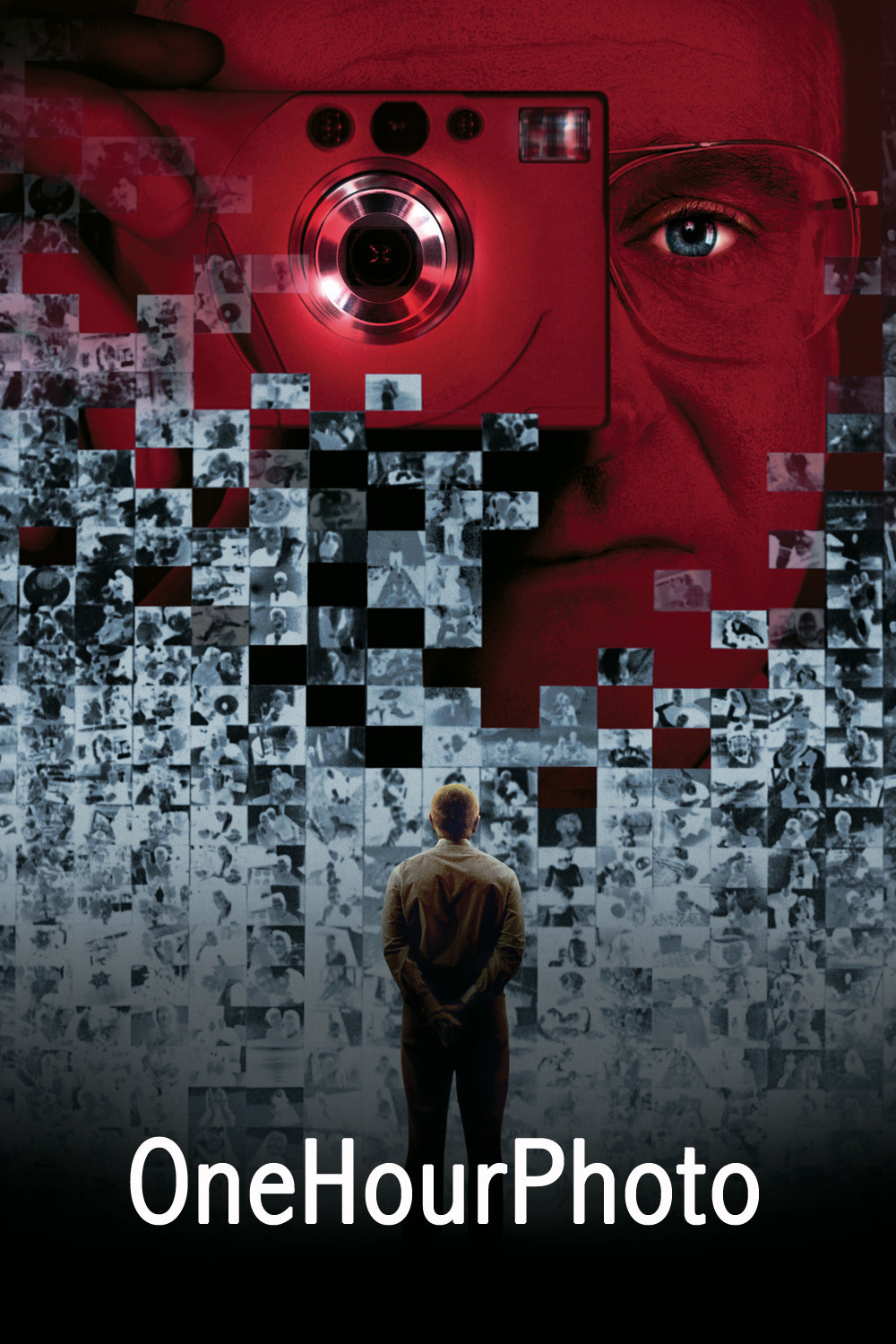

“One Hour Photo” tells the story of Seymour “Sy” Parrish, who works behind the photo counter of one of those vast suburban retail barns. He has a bland, anonymous face, and a cheerful voice that almost conceals his desperation and loneliness. He takes your film, develops it, and has your photos ready in an hour. Sometimes he even gives you 5-by-7s when all you ordered were 4-by-6s. His favorite customers are the Yorkins–Nina, Will and cute young Jake. They’ve been steady customers for years. When they bring in their film, he makes an extra set of prints–for himself.

Sy follows an unvarying routine. There is a diner where he eats, alone, methodically. He is an “ideal employee.” He has no friends, a co-worker observes. But the Yorkins serve him as a surrogate family, and he is their self-appointed Uncle Sy. Only occasionally does the world get a glimpse of the volcanic side of his personality, as when he gets into an argument with Larry, the photo machine repairman.

The Yorkins know him by name, and are a little amused by his devotion. There is an edge of need to his moments with them. If they were to decide to abandon film and get one of those new digital cameras, a prudent instinct might lead them to keep this news from Sy. Robin Williams plays Sy, another of his open-faced, smiling madmen, like the killer in “Insomnia.” He does this so well you don’t have the slightest difficulty accepting him in the role. The first time we see Sy behind his counter, neat, smiling, with a few extra pounds from the diner routine, we buy him. He belongs there. He’s native to retail.

The Yorkin family is at first depicted as ideal: models for an ad for their suburban lifestyle. Nina Yorkin (Connie Nielsen), pretty and fresh-scrubbed, has a cheery public persona. Will (Michael Vartan) is your regular clean-cut guy. Young Jake (Dylan Smith) is cute as a picture. Mark Romanek, who wrote and directed the film, is sneaky in the way he so subtly introduces discordant elements into his perfect picture. A tone of voice, a half-glimpsed book cover, a mistaken order, a casual aside … they don’t mean much by themselves, but they add up to an ominous cloud, gathering over the photo counter.

Much of the film’s atmosphere forms through the cinematography, by Jeff Cronenweth. His interiors at “Savmart” are white and bright, almost aggressive. You can hear the fluorescent lights humming. Through choices involving set design and lens choices, the One Hour Photo counter somehow seems an unnatural distance from the other areas of the store, as if the store shuns it, or it has withdrawn into itself. Customers approach it across an exposed expanse of emptiness, with Sy smiling at the end of the trail.

A man who works in a one-hour photo operation might seem to be relatively powerless. Certainly Sy’s boss thinks so. But in an era when naked baby pictures can be interpreted as child abuse, the man with access to your photos can cause you a lot of trouble. What would happen, for example, if Will Yorkin is having an affair, and his mistress brings in photos to be developed, and Uncle Sy “mistakenly” hands them to Nina Yorkin? The movie at first seems soundly grounded in everyday reality, in the routine of a predictable job. When Romanek departs from reality, he does it subtly, sneakily, so that we believe what we see until he pulls the plug. There is one moment I will not describe (in order not to ruin it) when Sy commits a kind of social trespass that has the audience stirring with quiet surprise: Surprise, because until they see the scene they don’t realize that his innocent, everyday act can be a shocking transgression in the wrong context.

Watching the film, I thought of Michael Powell’s great 1960 British thriller “Peeping Tom,” which was about a photographer who killed his victims with a stiletto concealed in his camera. Sy uses a psychological stiletto, but he’s the same kind of character, the sort of man you don’t much notice, who blends in, accepted, overlooked, left alone so that his rich secret life can flower. There is a moment in “Peeping Tom” when a shot suddenly reveals the full depth of the character’s depravity. In “One Hour Photo,” a shot with a similar purpose requires only a lot of innocent family snapshots, displayed in a way that is profoundly creepy.

The movie has also been compared to “American Beauty,” another film where resentment, loneliness and lust fester beneath the surface of suburban affluence. The difference, I think, is that the needs of the Kevin Spacey character in “American Beauty,” while frowned upon and even illegal, fall generally within the range of emotions we understand. Sy Parrish is outside that range. He was born with parts missing, and has assembled the remainder into a person who has borrowed from the inside to make the outside look OK.