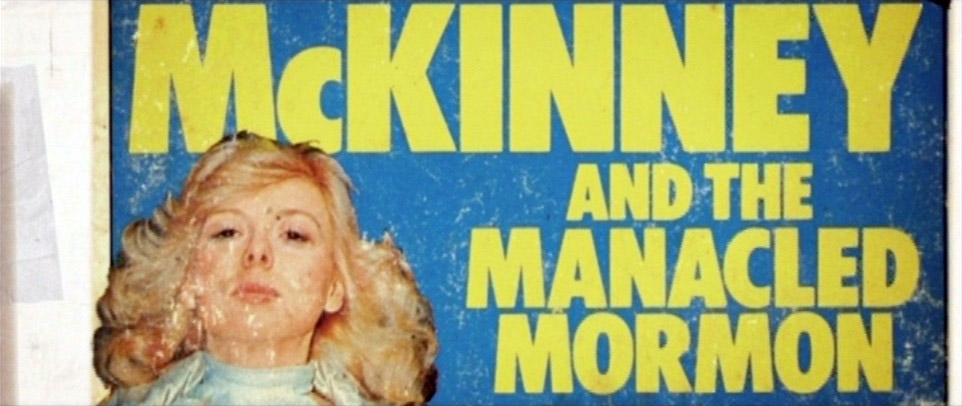

In 1977, McKinney was involved in the infamous “Case of the Manacled Mormon,” which was made to order for the British tabloids we’ve been reading about during the News of the World scandal. A former Miss Wyoming, she was alleged to have kidnapped an American Mormon missionary in the U.K., handcuffed him to a bed and made him a sex slave. All lies, she insists in “Tabloid,” and says she was intervening to rescue him from a cult. British police said she fled the country with an accomplice, then donned a red wig and flew into Canada where they posed as part of a mime troupe.

McKinney’s life seems ideal for sensational headlines. Years later, she found herself in the news again after a Korean scientist allegedly cloned her beloved dog, producing five puppies. In 2008, McKinney faced burglary charges in Tennessee while trying to find funds to purchase a false leg for her three-legged horse.

Is McKinney speaking the truth when she gives her version of the story? Or are the other versions offered by Morris more accurate? I believe Morris doesn’t think it matters. It is Joyce McKinney he cares about. How she presents herself, how she copes, who she is to herself, what she does to explain a bizarre and contradictory story. Watching the film is a tantalizing experience. Everything seems right here within our grasp, like truth in a philosophy class. Yet there are so many questions that cast truth into doubt. When you leave at the end, you may feel you have the necessary materials, but don’t know how to assemble them.

“Rashomon” will inevitably be evoked in discussions of this film. Many scenarios fit the facts. Morris presents officials with boundless reasons to think McKinney guilty of stalking, abduction and possible rape. He also allows McKinney to offer a perky alternative perspective on the same events. Her alleged victim is portrayed in murky ambiguity. (Once unshackled, he has prudently refused all interviews.) Morris surrounds his story with unexpected asides, blindsides us with surprise revelations, and weaves in an ominously and insidious score by John Kusiak.

Morris gained full access to McKinney, who in the early 1970s, was a somewhat shady nude model and is now a poised and persuasive sixtysomething, who proclaims full innocence and has an explanation for everything. As is often the case with Morris, we can never be sure what he thinks, only that he wants to baffle us with the impenetrable strangeness of reality.

Morris makes intensely personal films, which are neither about his subjects nor himself, but about the intensity of his gaze. No wonder he invented the Interrotron, which allows Morris and the person he is speaking with to peer directly into each other’s eyes. He, and we, are constantly asking what we think of this person — and what’s really going on here?

Even in his first film, “Gates of Heaven” (1978), Morris was looking but not judging. Every audience I’ve seen that film with has been divided about whether he loves its subjects or is mocking them. Impossible to say. And Joyce McKinney? She is so likable and sounds so plausible, and yet what was the deal with the red wig and the mime troupe? She sounds wounded in explaining her early nude photos are Photoshopped. But they sure do look like her — and how did they get printed in real magazines before the invention of Photoshop, and why would anyone back then have wanted to substitute her face on somebody else’s body?

What is amazing is that Morris gets McKinney to talk at all. And not only her, but others who were involved, all staring directly into the Interrotron and all sounding uncannily as if they’re speaking the truth. I’ve seen “Tabloid” twice. It is a spellbinding enigma, and one of the damnedest films Morris has ever made.

Note: This review incorporates material from my blog posts written at the 2010 Toronto Film Festival.