A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

“A sense of obligation.”

–Stephen Crane

That man can be found at the center of Werner Herzog‘s films. He is Aguirre. He is Fitzcarraldo. He is the Nosferatu. He is Timothy Treadwell, who lived among the grizzlies. He is Little Dieter Dengler, who needed to fly. She is Fini Straubinger, who lived in a land of silence and darkness since she was 12. He is Kaspar Hauser. He is Klaus Kinski. He is the man who will not leave the slopes of the Guadeloupe volcano when it is about to explode. He is those who live in the Antarctic. She is Juliana Koepcke, whose plane crashed in the rain forest and she walked out alive. He is Graham Dorrington, who flew one of the smallest airships ever built to study the life existing only in the treetops of that rain forest.

He is the sculptor Steiner, a ski-jumper who learned to fly so far the landing slopes could not contain him. He is the man or woman who left his handprint on the wall of the Chauvet Cave 32,000 years ago. He is Michael Perry, with days to go on Death Row. He is Woyzeck, who submitted without complaint to the medical experiments ordered by the German army. He is Dr. Gene Scott, who preached his gospel for long unbroken hours on cable TV, while seated wearing strange hats and smoking cigars. He is Hias, the man who stands on a mountaintop engulfed in tumbling clouds. He is the bad lieutenant. He is Herschel Steinschneider, the Jewish strongman in Nazi Germany. He is the alien seeking a new home for his people on Earth. He is Hercules. The man standing behind him is Herzog.

One year at Telluride, Herzog invited me up to his room in the New Sheridan Hotel to show me the VHS tape of his newest film, “Bells From the Deep.” It was about the people of a small village in Russia which stands on the bank of a lake. These people believe that at the bottom of the lake there is a city inhabited by angels. You can only see it on a few days every year when the ice is thin enough to see through, but not so thin they would crash in and drown.

Foot by foot, inch by inch, the villagers creep forward on the ice. They hear obscure groaning and moanings as the ice complains. Sometime a crack shoots out from them and they freeze, unsure whether to continue. Eagerly they peer into the ice, seeking the faces of the angels.

I don’t believe the film was ever released, perhaps because it lacked closure. The village people saw the angel city, and none of them drowned.

“That must have been you with a camea crawling on the ice behind them,” I said.

“I would not ask anyone to take a chance I would not take myself,” he said.

Then he told me that there was no village and he made the whole story up. I remember him at Cannes, after the premiere of “Where the Green Ants Dream” (1984). At the press conference, a journalist from Australia asked him the source for his information about Aboriginal beliefs. “There is no source,” he said. “They made up their beliefs, and I made up mine.”

For that matter, “Little Dieter Needs to Fly” (1997), a documentary based on the life of a man locked up for years in a Loatian prison camp, opens with a sequence in which the man arrives home and compulsively opens every door, cupboard and drawer in his house many times, to be sure they’re not locked. All made up. That doc was remade into “Rescue Dawn,” which centers on a jungle trek consisting of Dieter’s escape on a journey which had its details largely invented.

When he made “The White Diamond” (2004), he was again determined to take the chances himself. That was his documentary about Dorrington, the naturalist who believed there were forms of life living in the canopy of the rain forest that were born, lived and died without ever touching the earth. Because the fragile growth at that height will not permit climbing, Dorrington constructed the White Damond, a teardop-shaped airship with an open gondola, which would be lifted by a balloon to deliver the Diamond into the trees, where it could gingerly investigate the creatures he expected to find there.

Dorrington tested an earlier airship in 1993 in Sumatra, and that ended with catastrophe. His cinematographer, Dieter Plage, fell from the gondola after it was broken on the high branches of a tree by a sudden wind. “It was an accident,” says Dorrington, and all agree, but he blames himself every day. Now he is ready to try again.

Before the first test flight, Herzog has an argument with Dorrington. The scientist wants to fly solo. Herzog calls it “stupid” that the first flight might take place without a camera on board. It might be the only flight. Herzog brought along two cinematographers, but insists he must personally take the camera up on the maiden voyage. “I cannot ask a cinematographer to get in an airship before I test it myself,” he says.

Up they go, the two men dangling in the teardrop. There are some dicey moments when the ship goes backward when it should go forward, and Herzog observes a motor burning out and pieces of a propeller whizzing past his head. The ship skims the forest canopy before it descends to dip a toe in the river.

Mournful, ecclesiastical music accompanies these images. The vast Kaieteur Falls fascinates the party; its waters are golden-brown as they roar into a maelstrom, while countless swifts and other birds fly into a cave behind the curtain of water. Mark Anthony Yhap, a Rastafarian employed by the expedition, tells them legends about the cave. The team doctor, Michael Wilk, has himself lowered on a rope with a video camera to look into the cave. It is typical of a Herzog project that the doctor would be “an experienced mountain climber.” It is sublimely typical that Herzo doesn’t show us the doctor’s footage of the cave, after Yhap argues that its sacred secrets must be preserved. What is in the cave? A lot of guano, is my guess.

Herzog insists to the universe: Sir, I exist! Another year at Telluride, he and his small team had just returned after a failed shoot on top of a mountain. It was a clear day but a freak storm blew up and buried them in snow. They dug themselves out and climbed back down.

Herzog is three months younger than I am. His people and my German relatives are from Munich. It isn’t impossible that we’re distant cousins. That first time I met him was at somebody’s apartment in Greenwich Village during the New York Film Festival. I sat on the rug at his feet. What we talked about I have no idea, but I felt a strong connection and I’ve felt it ever since. He was a kid with a film at the festival, yet so more than that.

Other kids like him have grown up to make blockbusters and command millions of dollars for budgets, but Herzog has never wavered. He has made the films he chooses, as he chooses, and now at 70 and with 47 directorial credits, he has never made a film to be ashamed of. How he finances them I do not know, but it’s not from the profits of his previous films. Asked what he would do if told the world were ending tomorrow, he said, “Martin Luther said he would plant a tree. I would start a film.”

One year he came to Ebertfest and told us his journey to Urbana began on top of a plateau in South America, from which he had himself lowered by ropes down the side, and trekked with tribesmen to a river where a dugout canoe took him to a city with a steamship. One of the Far-Flung Correspondents told me: “He wouldn’t have come otherwise. It was the difficulty that made it irresistible.”

Everybody knows the story of how, in November 1974, Herzog learned that the great German cineaste Lotte Eisner was near death at 78. A survivor of the Nazi camps, she had settled in Paris and helped found the Cinematheque Francais. During World War II she was interned in a Nazi camp. After the war she worked closely with Henri Langlois, founder of the Cinemateque Française, as the chief archivist. Carrying a backpack and wearing new boots, Herzog walked from Munich to her bedside

Werner Herzog wrote in his journal, “This must not be, not at this time; German cinema could not do without her now.” So, in a gesture of iron-willed control over apparently dark inevitability, Herzog decided to walk from his home in Munich to Paris to visit Eisner, convinced that if he did so, she would recover. Herzog set off on what will be a three-week odyssey equipped with land backpack and a new pair of boots.

John Bailey of the American Society of Cinematographers wrote in the ASC Journal: “Herzog’s confrontation with the raw elements of an early winter and its assault on his body reads as an analogue for that of many of his fictional characters, who also face down and are battered by implacable if not outright hostile Nature. Neither Aguirre, Fitzcaraldo, nor Dieter Dengler lives in a time and space continuum much different from that which Herzog faced on this journey. If the sheer physical discomfort he endured–from rain, ice, snow, chilling wind, suspicious peasants and farmer– were a measure of grace gained, then Lotte Eisner, who died in 1983 at 87, would still be alive.”

Herzog is open to less noble challenges. When he was living in Berkeley in the 1970s, the Telluride co-founder Tom Luddy introduced him to a young man named Errol Morris, who was making “Gates of Heaven,” a feature documentary about a pet cemetery. “If you finish that film, I will eat my shoe,” Herzog told him. Morris finished the film and Herzog ate his shoe. Luddy was running the Pacific Film Archive at the time, and arranged for Herzog to eat his shoe onstage after it had been made more palatable by Alice Waters, of Chez Panisse. I recall hot sauce and bay leaves.

Herzog’s new film, “Happy People: A Year in the Tiaga,” is a new unfolding of his life in search of the extremes. Having made “Encounter at the End of the World” (2007) about the occupants of a research station at the South Pole, wasn’t it inevitable for him to turn to those who live in Siberia, inside the Arctic Circle? These hunters and trappers in a village of about 400 live off the land with their own hands and resources. The first generation was set down there by the Soviet Communist government and directed to hunt, fish and trap for fur. The airlift didn’t return on schedule and they lived in an unheated hut, with no winter clothing, no firewood and hardly any tools. One of the survivors of that time tells the camera that one of the early settlers “didn’t make it. I guess he didn’t have what it takes.”

The film is divided reasonably into Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn. Each season is triggered to prepare for the next. In early autumn they’re knocking on trees to dislodge nuts for their winter meals. Their nets capture pike that will be salted away. They use moss and other insulations to weather-proof their cottages. They aren’t entirely without modern equipment; we see chainsaws, steel axes and hatchets, outboard engines and motorbikes. They wear modern outdoor clothing. In this land where everything is stretched taut, one man allows himself the luxury of cigarettes.

The film pays close attention to what they do and how they do it. They hollow and shape a log of just the right size for a dugout canoe, use wedges to push its sides apart, and fix it in shape with fire. They make tar from tree bark to caulk it. They slice wood from the sides of trees and construct their skis. They use smaller trees to set their spring-loaded animal traps; hundreds of traps for each man. In their hands a steel hatchet reduces each tree to their needs, and we reflect that technology like stone axes, wooden wedges and levers were used by our earliest ancestors. We learn how they’re able to avoid carving the sides of a dugout too thin, How they shave, soften and shape their skis. How they paint themselves with tar to repel the clouds of mosquitoes. How their lives entwine with the lives of sables.

The people of the Taiga speak to the camera and are used voice-over as they explain how and why they do things. Herzog adds his own narration, a mixture of measured explanation, wonder and the implacable nature of what is being described. Steven Boone, who wrote this acutely observant review of “Happy People” on my website, calls it The Voice: “The films could probably stand on their own merits without That Voice, but why should they?” Boone describes the men of the Tigra: “They live off the land and are self reliant, truly free. No rules, no taxes, no government, no laws, no bureaucracy, no phones, no radio, equipped only with their individual values and standard of conduct.” The Voice has no tones for sentimentality.

One element of “Happy People” struck me. My DVD had to skip over a “damaged area” and I may have missed them, but I recall no women in the film. How can that be? There are children. The great undiscovered continent of the Herzogian cinema is the female gender. They’re there –but serving supporting roles. It is not that he avoids strong, talented women. His wife Lena is a Russian-born photographer who works for major publications, has gallery shows, and has published four books of her work.

The “co-director” of “Happy People” is a Russian cinematographer named Dmitry Vasyukov. It didn’t surprise me to learn that Herzog himself wasn’t in Siberia to shoot the footage. He was shown four hours of it by a friend in Los Angeles, and determined to edit and narrate the material. His film that focuses uncompromisingly on these men and their lives, and subscribes adamantly to how he “Fitzcarraldo” describes Nature: “Overwhelming and collective murder.”

He made at least one other film edited mostly from someone else’s work: the great success “Grizzly Man” (2005). Timothy Treadwell lived among the grizzlies in Alaska every Summer for years until one Autum a bear attacked him and his girlfriend, killed them and ate them.

In his narration for that film, Herzog says: “And what haunts me, is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature. To me, there is no such thing as a secret world of the bears. And this blank stare speaks only of a half-bored interest in food. But for Timothy Treadwell, this bear was a friend, a savior.”

I believe Herzog has a conviction that our civilization teeters on the brink of collapse, and that those who live may have to so by their wills and skills. If global warming takes its toll, the people of the Tiaga will be well-located and equipped to survive. They will be even happier when it’s summertime, and the living’ is easy.

¶

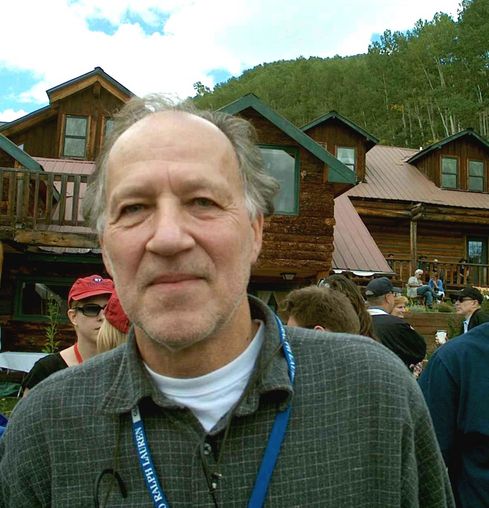

Photos by Roger Ebert: Top of page shows Herzog at the Founder’s Day Picnic at Telluride 2002; festival co-director Telluride director Tom Luddy is in right background facing this way, wearing a baseball cap. Photo at Toronto 2010 at the “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” premiere is with his wife Lena.¶

This is an unusually good trailer:

¶

“The Great Ecstasy of the Sculptor Steiner.” The complete film by Werner Hergog. Herzog’s Man, eyes fixed on the stars, alone.

¶

“Bells From the Deep.” The complete film about the Russians crawling on thin ice to behold angels.

¶

“Happy People: A Year in the Taiga”

★ ★ ★ 1/2

Music Box Films presents a documentary by Dmitry Vasyukoy and Werner Herzog. Written by Herzog, Rudolph Herzog and Vasyukov. Running time: 90 minutes. No MPAA rating.