Werner Herzog’s documentary “The White Diamond” is not about a diamond but about an airship, one of the smallest ever built, designed to float above the canopy of equatorial rain forests. Every niche in the jungle is exploited by plants, animals and insects that have evolved to make a living there, and biologists believe that undiscovered species might live their entire lives 80 or 120 feet from the ground.

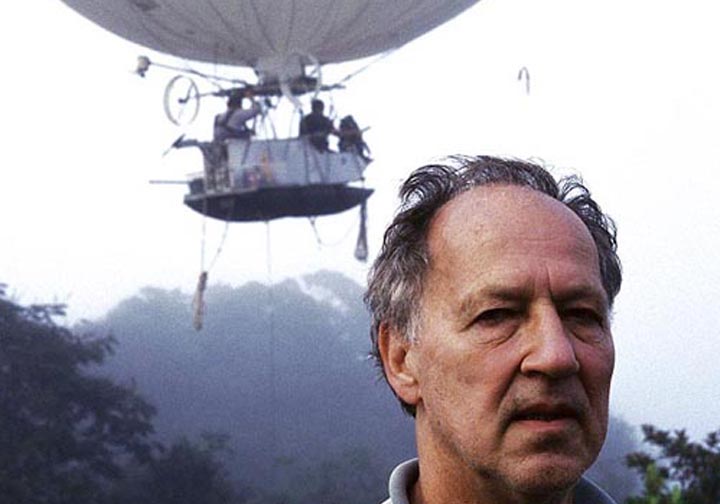

Herzog introduces us to a London researcher named Graham Dorrington, who dreams of reaching out from his airship to study specimens on the ceiling of the jungle. Like many of Herzog’s subjects, he is a dreamer who talks a little too fast and smiles when he doesn’t seem to be happy: When a sudden storm threatens to tear his airship to pieces, he says he is philosophical, and we see that he isn’t.

Dorrington’s airship is shaped like an upside-down teardrop with a tail. It carries a two-man gondola and is powered and steered by small motors. It uses helium gas, which will not burn, unlike hydrogen gas, which caught fire inside the Hindenburg and brought at end to an era when the giant Zeppelins served tourist routes connecting Europe, Brazil, India and the United States. The Zeppelins were cigar-shaped ships that were hard to turn, Dorrington says, unlike his ship, which can pivot in the air. That is the theory, anyway, as he explains his motors and his switches and we hear the voice of Herzog, always filled with apprehension, telling us, “He did not know then that this particular switch would cause a huge problem later.”

Dorrington tested an earlier airship in 1993 in Sumatra, and that ended with catastrophe, Herzog tells us. Dorrington describes the death of his cinematographer, Dieter Plage, who fell from a gondola after it was broken on the high branches of a tree by a sudden wind. “It was an accident,” Dorrington says, and all agree, but he blames himself every day. Now he is ready to try again.

His airship was built in a huge hangar outside London that once housed dirigibles. Strange, that it cannot be tested there, but must be transported to South America and the rain forests of Guyana. Dorrington is a man after Herzog’s heart — Herzog, the director who could have filmed “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” and “Fitzcarraldo” a few miles from cities, and insisted on filming them hundreds of miles inside the rain forest. Herzog has made a specialty of finding obsessives and eccentrics who push themselves to extremes; see his current doc, “Grizzly Man,” about Timothy Treadwell, who lived among the bears of Alaska until one killed him.

Now watch what happens during the first test flight. Herzog has an argument with Dorrington. The scientist wants to fly solo. Herzog calls it “stupid” that the first flight might take place without a camera on board. (It might, of course, be the only flight.) Herzog has brought along two cinematographers, but insists he must personally take the camera up on the maiden voyage. “I cannot ask a cinematographer to get in an airship before I test it myself,” he says. As Herzog buckles himself into the gondola, we reflect that if Dorrington’s standards were those that Herzog insists on, Dorrington would not allow Herzog to get in the airship until he had tested it himself. It is sublimely Herzogian that this paradox is right there in full view.

There are some dicey moments when the ship goes backward when it should go forward, and Herzog observes a motor burning out and pieces of a propeller whizzing past his head. The flight instructor who pilots the expedition’s ultralight aircraft says Dorrington has not practiced “good airmanship.” Dorrington moans that “seven different systems” failed. We wonder if the catastrophe in Sumatra will be repeated.

There is breathtaking footage of the ship’s flights, as it skims the forest canopy, and descends to dip a toe in the river. Mournful, vaguely ecclesiastical music accompanies these images. The vast Kaieteur Falls fascinates the party; its waters are golden-brown as they roar into a maelstrom, and countless swifts and other birds fly into a cave behind the curtain of water. Mark Anthony Yhap, a local man employed by the expedition, relates legends about the cave. The team doctor, Michael Wilk, has himself lowered on a rope with a video camera to look into the cave. It is typical of a Herzog project that the doctor would be “an experienced mountain climber.” It is sublimely typical of Herzog that he does not show us the doctor’s footage of the cave, after Yhap argues that its sacred secret must be preserved. What is in the cave? A lot of guano, is my guess.

There are times when this expedition causes us to speculate that the Monty Python troupe might have based its material on close observation of actual living Britons. Consider the “experiment” to determine if the downdraft of the waterfall is so strong it would threaten the airship. Dorrington and Herzog tie together four brightly colored birthday balloons and hang a glass of champagne from them as ballast. Sure enough, the balloons are sucked into the mist.

Mark Anthony Yhap is one of the film’s riches. Known as “Redbeard,” he is a Rastafarian who gives the film its title, saying the airship looks like a “big white diamond floating around in the sunrise.” Yhap is fond of his red rooster, a mighty bird that has five wives who present him with five eggs every morning. Toward the end of the film Yhap is given his own chance to ride in the airship and enjoys it immensely, but regrets that he could not take along his rooster.

Although “The White Diamond” is entire of itself, it earns its place among the other treasures and curiosities in Herzog’s work. Here is one of the most inquisitive filmmakers alive, a man who will go to incredible lengths to film people living at the extremes. In “La Soufriere,” a 1977 documentary released on DVD last month, he journeys to an island evacuated because of an impending volcanic eruption, to ask the only man who stayed behind why he did not leave. What he is really asking, what he is always asking, is why he had to go there to ask the question.