“Men are often haunted,” Werner Herzog tells us at the beginning of “Little Dieter Needs to Fly.” “They seem to be normal, but they are not.” His documentary tells the story of such a haunted man, whose memories include being hung upside down with an ant nest over his head, and fighting a snake for a dead rat they both wanted to eat.

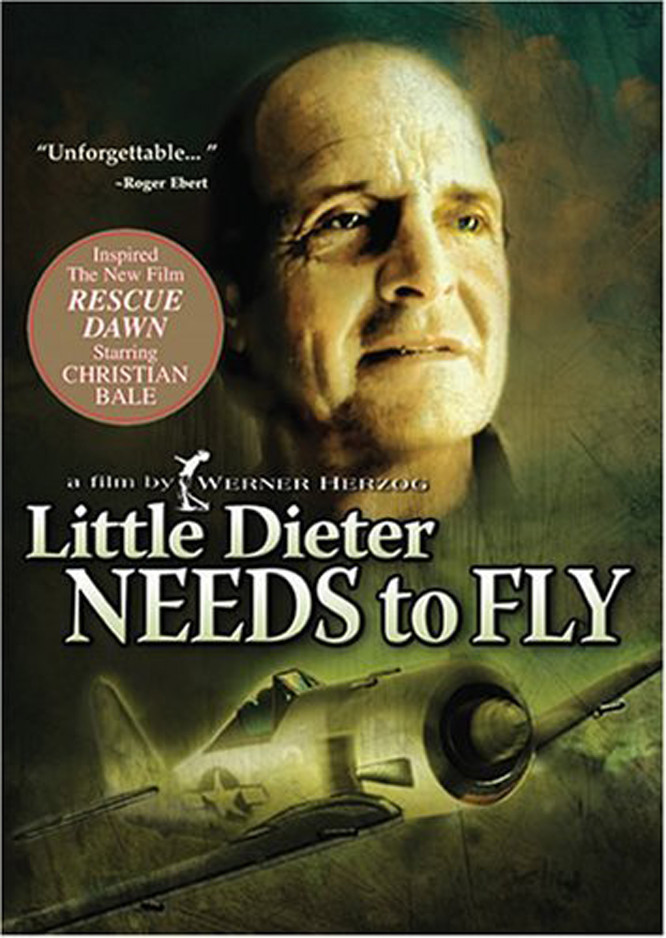

The man’s name is Dieter Dengler. He was born in the Black Forest of Germany. As a child, he watched his village destroyed by American warplanes, and one flew so close to his attic window that for a split-second he made eye contact with the pilot flashing past. At that moment, Dieter Dengler knew that he needed to fly.

Dengler is now in his 50s, a businessman living in Northern California. He invites us into his home, carefully opening and closing every door over and over again, to be sure he is not locked in. He shows us the stores of rice, flour and honey under his floor. He obsesses about being locked in, about having nothing to eat. He tells us his story.

As an 18-year-old, he came penniless to America. He enlisted in the Navy to learn to fly. He flew missions over Vietnam, but “that there were people down there who suffered, who died–only became clear to me after I was their prisoner.” He was shot down, made a prisoner, became one of only seven men to escape from prison camps and survive. He endured tortures by his captors and from nature: dysentery, insect bites, starvation, hallucinations.

Werner Herzog’s “Little Dieter Needs to Fly” lets Dieter tell his own story, which he does in rushed but vivid English, as if fearful there will not be time enough if he doesn’t speak fast. As he talks, Herzog puts him in locations: His American home, his German village of Wildberg, and then the same Laotian jungles where he was shot down. Here certain memories are re-enacted: He is handcuffed by villagers, made to march through the forest, and demonstrates how he was staked down at night. “You can’t imagine what I’m thinking,” he says.

The thing about story-telling is that it creates pictures in our heads. I can “see” what happened to Dieter Dengler as clearly as if it has all been dramatized, and his poetry adds to the images. “As I followed the river, there was this beautiful bear following me,” he remembers. “This bear meant death to me. It’s really ironic–the only friend I had at the end was death.” At another point, standing in front of a giant tank of jellyfish, he says, “This is basically what Death looks like to me,” and Herzog’s camera moves in on the dreamy floating shapes as we hear the sad theme from “Tristan and Isolde.” Now here is an interesting aspect. Dieter Dengler is a real man who really underwent all of those experiences (and won the Medal of Honor, the D.F.C and the Navy Cross because of them). His story is true. But not all of his words are his own. Herzog freely reveals in conversation that he suggested certain images to Dengler. The image of the jellyfish, for example–“that was my idea,” Herzog told me. Likewise the opening and shutting of the doors, although not the image of the bear.

Herzog has had two careers, as the director of some of the strangest and most fascinating features of the last 30 years, and some of the best documentaries. Many of his docs are about obsessed men: The ski-jumper Steiner, for example, who flew so high he overjumped his landing areas. Or Herzog himself, venturing onto a volcanic island to interview the one man who would not leave when he was told the volcano would explode.

Herzog sees his mission as a filmmaker not to turn himself into a recording machine, but to be a collaborator. He does not simply stand and watch, but arranges and adjusts and subtly enhances, so that the film takes the materials of Dengler’s adventure and fashions it into a new thing.

You meet a person who has an amazing story to tell, and you rarely have the time to hear it, or the attention to appreciate it. The attendants in nursing homes sit glued to their Stephen King paperbacks; the old people around them have stories a thousand times scarier to tell. A colorful character dies and the obituaries say countless great stories were told about him–but at the end, did anybody still care to listen? Herzog starts with a balding middle-aged man driving down a country lane in a convertible, and listens, questions and shapes, until the life experience of Dieter Dengler becomes unforgettable. What an astonishing man! we think. But if we were to sit next to him on a plane, we might tell him we had seen his movie, and make a polite comment about it, and go back to our magazine. It takes art to transform someone else’s experience into our own.