Werner Herzog believes in the voodoo of locations, in the possibility that if he shoots a movie in the right place and at the right time, the reality of the location itself will seep into the film and make it more real. He has filmed on the slopes of active volcanoes and a thousand miles up the Amazon, and in his new movie, “Where the Green Ants Dream,” he goes to a godforsaken, heat-baked stretch of Australian Outback. This is grim territory, but it is sacred land to the Aborigines, who believe that this is the place where the green ants go to dream, and that if their dreams are disturbed, unspeakable calamities will rain down on future generations. The Aborigines’ belief is not shared by a giant mining company, which wants to tear open the soil and search for uranium.

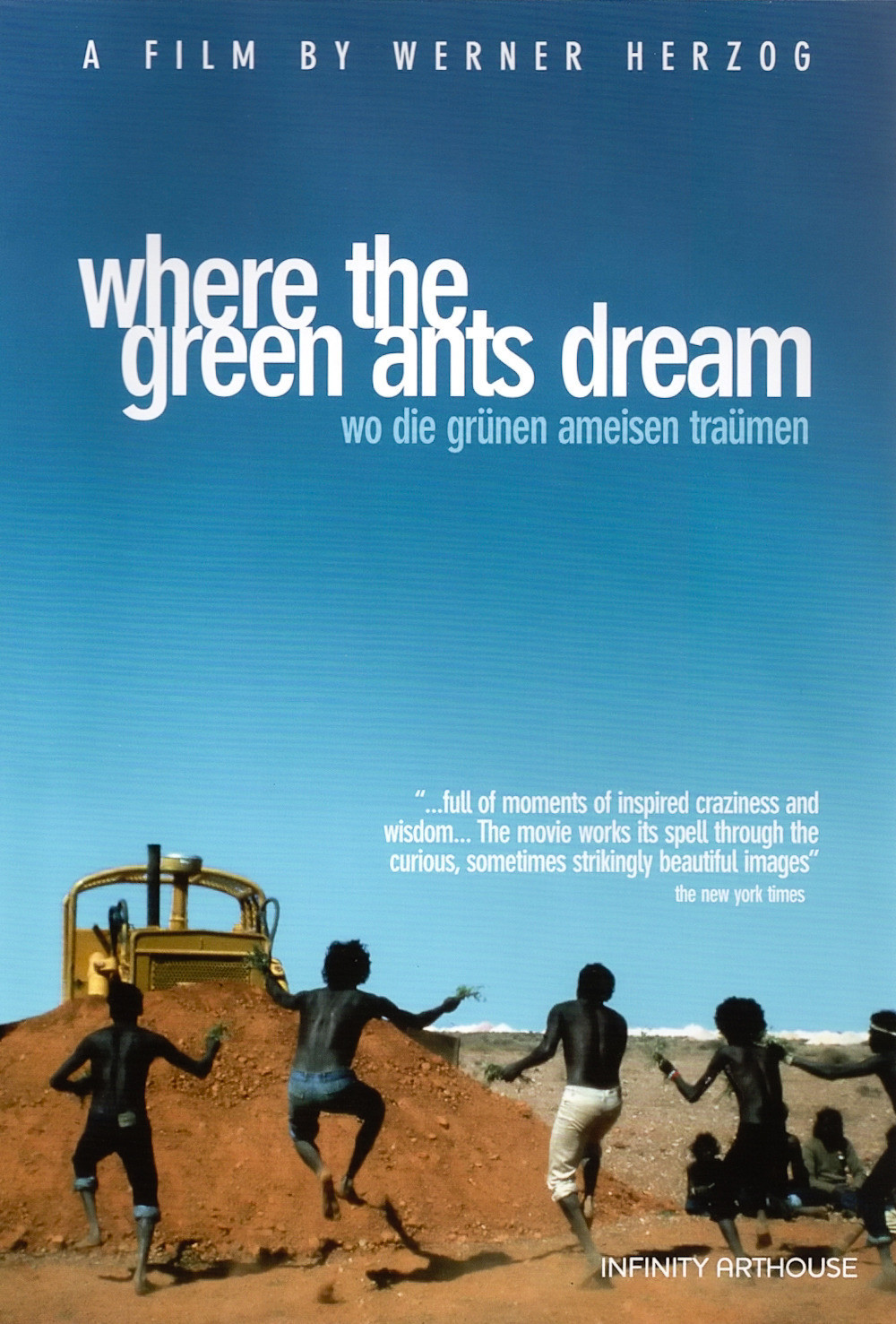

As the movie opens, the company is in the process of setting off explosions, so geologists can listen to the echoes and choose likely mining sites. The Aborigines sit passively in the way of the explosions, refusing to move, insisting that the ants must not be awakened. We meet the characters on both sides: the tall, gangly mining engineer, the implacable tribal leaders, the supercilious president of the mining company, and the assorted eccentrics who have washed up on this desert shore.

Herzog has said that he thinks in images, not ideas, and that if he can find the correct pictures for a film, he’s not concerned about its message. In “Where the Green Ants Dream,” his images include an old woman sitting patiently in the Outback, an opened can of dog food on the ground in front of her, waiting for a pet dog that has been lost in a mine shaft. Then we see a group of Aborigines sitting in the aisle of a supermarket, on the exact spot where the last tree in the district once stood; it was the tree under which the men of the tribe once stood to “dream” their children before conceiving them. We also see an extraordinary landscape, almost lunar in its barren loneliness.

We do not see any ants, but then perhaps that is part of Herzog’s plan. One of the strangest things about this film (strange if you are not familiar with Herzog, who is the strangest of all living directors) is that nothing in this movie is based on anthropological fact. The beliefs, customs, and behavior of the Aborigines, for example, are not inspired by research into their actual lives — but are a fiction, made up by Herzog for his screenplay. The confrontation between the mining company and the Aborigines is likewise not based on yesterday’s headlines, but is symbolic, representing for Herzog similar “real” stories, but in a more dramatic form. Even the details about the life cycles of the ants are made up; Herzog has no idea if there are really ants in the Outback.

But there is a reality, nevertheless, in this odd film, and it comes out of the two conflicting sets of beliefs. The Aborigines sit and wait, inspired by deep currents of faith and tradition, and the engineers are always in motion, convinced that success lied in industry and activity. The conflict is everywhere in the world today, and Herzog didn’t need to make it up, only to find the pictures for it.