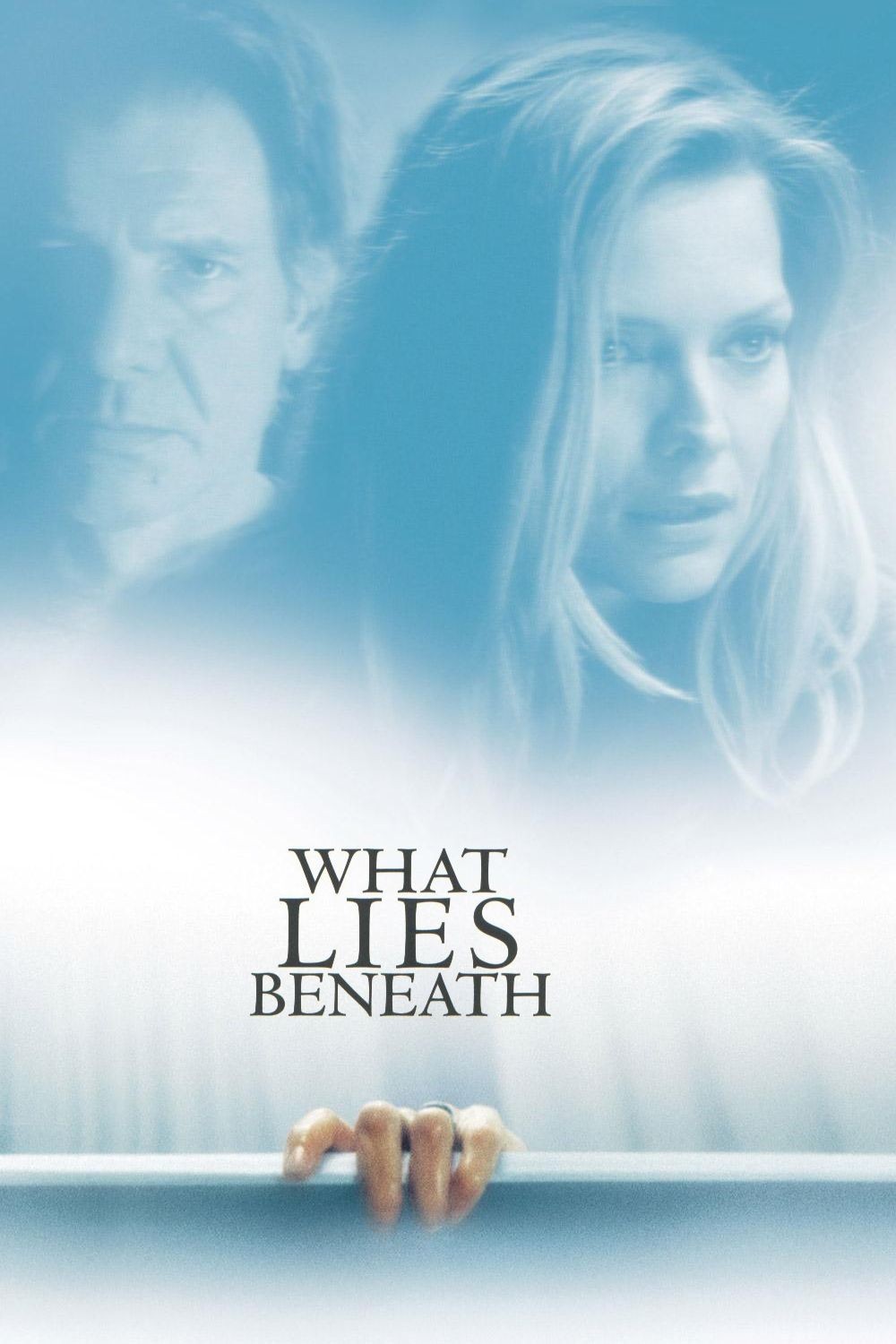

“What Lies Beneath” opens with an hour or so of standard thriller scare tactics, done effectively, and then plops into a morass of absurdity. Lacking a smarter screenplay, it milks the genuine skills of its actors and director for more than it deserves, and then runs off the rails in an ending more laughable than scary. Along the way, yes, there are some good moments.

Michelle Pfeiffer stars as Claire Spencer, the happily married wife of Dr. Norman Spencer (Harrison Ford), a scientist. They’re renovating his old family house on the shores of a lake–a house, which, when she is home alone, seems haunted–with doors that open by themselves, picture frames that keep falling over, a tub that fills itself, a dog that barks at invisible menaces and a neighbor who has possibly murdered his wife.

Gruff, no-nonsense Dr. Spencer of course dismisses his wife’s fears and sends her to a psychiatrist. All of her early scenes are reasonable enough, even if the doors open themselves two or three times more than necessary. It’s when we start to learn the motivation for the manifestations that we grow first restless, finally incredulous.

There’s a bag of tricks that skillful horror directors use, and they’re employed here by Robert Zemeckis (“Back To The Future,” “Forrest Gump“), who has always wanted, he says, to make a suspense film–“perhaps the kind of film Hitchcock would have done in his day,” according to his producer, Jack Rapke. Hitchcock would not, however, have done this film in his day or any other day, because Hitchcock would have insisted on rewrites to remove the supernatural and explain the action in terms of human psychology, however abnormal.

Zemeckis does quote Hitchcock; there’s a scene where Pfeiffer spies on a neighbor with binoculars and is shocked to see the neighbor spying back, and we are reminded of “Rear Window.” He also uses such dependable devices as harmless people who suddenly enter the frame and startle the heroine. And mirrors that suddenly reveal figures reflected in them. And shots where we are looking at a character in front of windows, and the camera slowly pans, causing us to expect a face to appear in the window.

All of these devices are used with journeyman thoroughness in “What Lies Beneath,” but they are only devices, and we know it. Late in the film, when the heroine walks close to the hand of a character who is assumed to be dead, the audience laughs because it knows–or thinks it knows–that in a horror film no one is ever really dead on the first try. Such devices at least involve the physical world and the laws of nature as we understand them. What’s happening in the supernatural scenes I leave you to decide; I think some of them are supposed to be real, others hallucinations, others seen in different ways by different characters.

Pfeiffer is very good in the movie; she is convincing and sympathetic and avoids the most common problem for actors in horror films–she doesn’t overreact. Her character remains self-contained and resourceful, and the sessions with the psychiatrist (Joe Morton) are masterpieces of people behaving reasonably in the face of Forces Beyond Their Comprehension. Ford is the most reliable of actors, capable of many things, here required to be Harrison Ford. The Law of Economy of Character Development requires that his husband be other than he seems, since he isn’t needed as his wife’s confidant and sidekick (Diana Scarwid’s character fills that slot). As for the possibly wife-killing neighbor, I can forgive that red herring almost anything because it pays off in a flawless sight gag at a party.

I’ve tried to play fair and not give away plot elements. That’s more than the ads have done. The trailer of this movie thoroughly demolishes the surprises; if you’ve seen the trailer, you know what the movie is about, and all of the suspense of the first hour is superfluous for you, including major character revelations. Don’t directors get annoyed when they create suspense and the marketing sabotages their efforts? The modern studio approach to trailers is copied from those marketing people who stand in the aisles of supermarkets, offering you a bite of sausage on a toothpick. When you taste it, you know everything there is to be known about the sausage, except what it would be like to eat all of it. Same with the trailer for “What Lies Beneath.” I like the approach where you can smell the sausage but not taste it. You desire it just as much, but the actual experience is still ahead of you. Trailers that give us a smell and not a taste; that’s what we need.