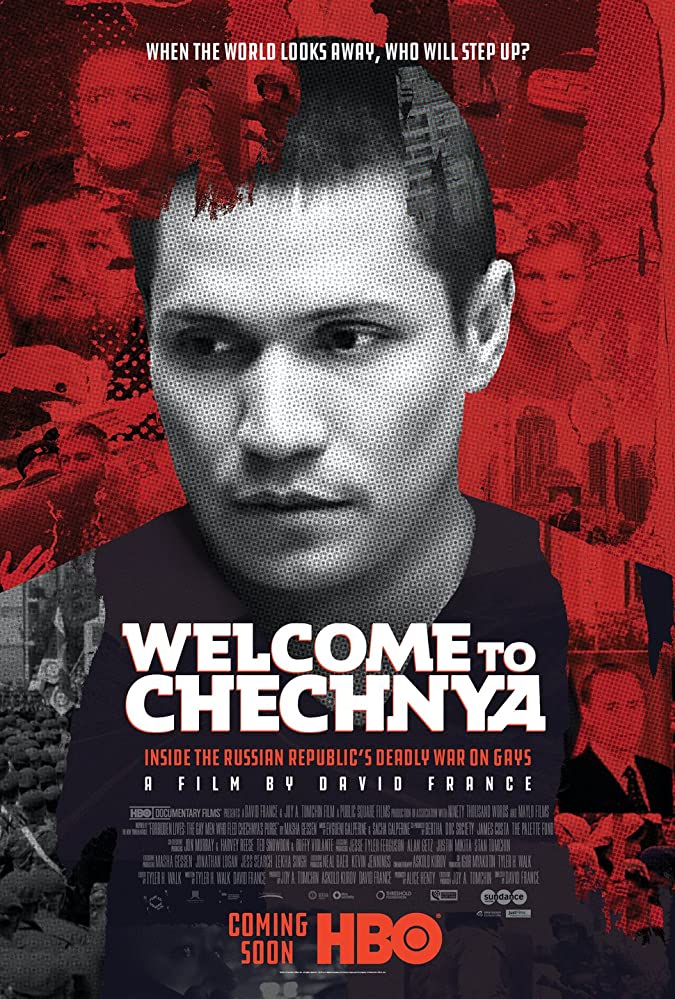

Documentarian David France faced an unenviable challenge with his latest film, “Welcome to Chechnya.” Moved by the plight of queer people trying to escape government-sanctioned persecution of the Russian state’s LGBTQ community, he embedded himself in the rescue efforts to smuggle out refugees to safer corners of the world. But in order to tell this story, most of his subjects would need to keep their identities hidden for safety.

The director, who has explored LGBTQ history in his movies “How to Survive a Plague” and “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson,” was now capturing history in the making, one so terrifying and disturbing, he can’t bear (or risk) to show in its entirely. It’s still happening, and some of the subjects in the film remain unaccounted for or in limbo. Instead of relying on traditional means of hiding someone’s identity in an interview—think of shadowy figures with altered voices or an off-screen disembodied narrator—France uses “deepfake” technology to overlay their faces with that of volunteers’, obscuring their identifiable features and allowing the filmmaker to show their side of the story: the heartbreak, agony, loneliness, fear and uncertainty of fleeing your homeland for your life.

In 2017, news began to spread that members of the LGBTQ community in the Russian state of Chechnya were being arrested by police and tortured or killed by strangers or relatives because of their sexual orientation. Under the Putin-approved leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, Chechnya began violating its queer citizens’ rights, with little recourse for justice. Despite efforts to muzzle the news, queer activists and organizations around the world and in Russia, like the Russian LGBT Network, began helping persecuted individuals, their partners and families to escape a country that had turned a blind eye to the death of its people by their neighbors.

With names and identities hidden to keep the subjects safe, France and cinematographers Askold Kurov and Derek Wiesehahn earn unprecedented access to survivors of Chechnya’s targeted persecution. His documentary shows horrifying photographic evidence of torture, and listens intently when a survivor calmly shares his horrifying experience of watching others die or brutalized by police with his shocked boyfriend. Interspersed throughout the documentary are activist-obtained videos showing what’s at stake for those who don’t leave in time: a cruel death at the hands of strangers or worse, their families. The images cut to black before gruesome endings, but the cruelty is unmistakable. Evgueni Galperine and Sacha Galperine score the film with a discordant, uneasy sound, the kind of off-putting rhythm to make a viewer uncomfortable listening as they are watching the horrors unfold.

That’s not to say the deepfake effect isn’t weird. It stands out once you notice the blurry edges of their face or how their features never seem to come into full focus. But the purpose of the deepfake mask is not that it looks so flawless that it suspends your disbelief. It’s so that Chechen officials can’t track down the people who have fled their clutches. At times, the new digital faces may become distracting or the identities and details of their stories may blur along with the subjects’ faces, but the impact of their testimonies remains strong. It allows the subjects of the film to speak as they would to someone in the room with them. We can see the good, the bad, and the difficult side of fleeing for your life from the government. We see one of the Chechen refugees attempt suicide, another one leaves without a trace never to be seen again. It’s a fate that’s even fallen on a Chechen pop star, Zelim Bakaev, who disappeared and has yet to be found. Leaving the country is sometimes just as precarious as leaving the state, as visa issues and isolation do little to raise the refugees’ spirits. The process also affects them mentally and emotionally as they’re losing a shared language, culture, family, friends, their entire lives once they leave.

The film features two members of the Russian LGBT Network, David and Olga, separately in a traditional interview format. Their exhaustive knowledge on the situation fills in the gaps to the news stories you might have heard. One brave soul, Maxim, decides to fight back against the inhumane treatment and take the Chechen officials to court, revealing his name in the process. When Maxim tells the press his story, the fake digital mask melts away revealing just how effective it was in hiding the documentary’s participants.

“Welcome to Chechnya” is both astonishingly groundbreaking in its use of technology, and difficult to watch. It potentially opens new doors to filmmakers and journalists as a way to protect at-risk sources or subjects, but the technology is still in its infancy. Yet, the story “Welcome to Chechnya” is tells would be very difficult without its hidden cameras and digital masking. The film puts together these harrowing stories and brings them to a terrifying conclusion: intolerance continues to spread in the region, as Chechnya’s neighboring states feel emboldened by the lack of oversight and repercussions to enact their own violence against their queer residents. The documentary finishes on a bleak note, but it doesn’t have to stop there. The full story of Chechnya’s persecution of the LGBTQ community has yet to be written. There’s still time to change the ending.