Then, miraculously, a cocktail of several drugs, including AZT, was tried along with protease inhibitors that prolonged its effectiveness. One of the survivors of that time recalls it in David France’s documentary “How to Survive a Plague.” Symptoms seemed to reverse themselves. Cancerous skin lesions disappeared. Patients began to gain weight. Within a month, blood counts were near normal, and health seemed to be restored. Many found it hard to believe, and still today feel some guilt that they are alive while millions around the world have died.

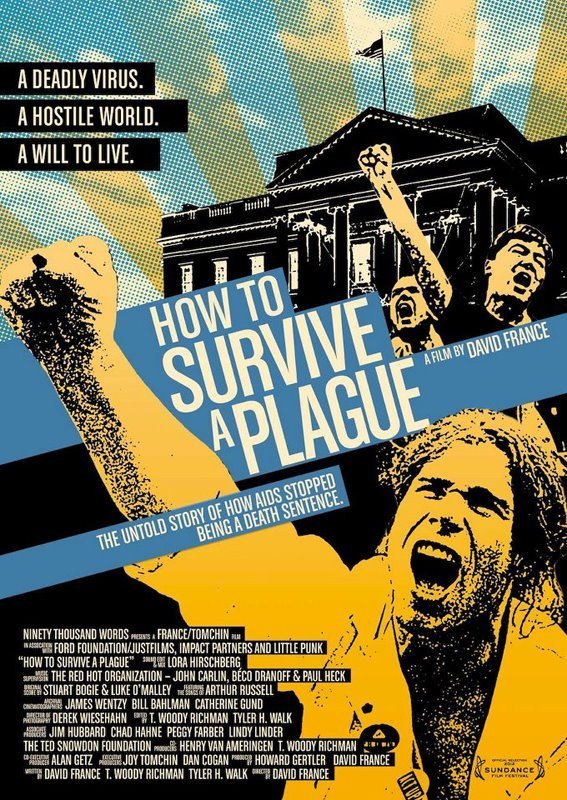

The documentary charts the rise of the AIDS crisis from its earliest days. It benefits enormously by a wealth of video footage taken by ACT UP and other groups, showing urgent meetings of victims, who demonstrated and even demanded arrest outside federal and municipal buildings and hospitals.

That was effective in raising awareness of a calamity so stigmatized that President Ronald Reagan scarcely even mentioned; George H.W. Bush noted it was caused by behavior and recommended “change your behavior” — scant comfort for those staring death in the face. Bill Clinton, on the campaign trail, was scarcely in the forefront of the cause and seems startled when he is the target of demonstrations.

But AIDS activism was not limited to demonstrations. The film spotlights scientists, researchers and a retired chemist, not all of them HIV-positive, who did invaluable work in calling attention to a treatment protocol and promising drugs worldwide. Surprisingly, they won seats on boards overseeing the crisis, as one federal official observes: “They know more than we do.”

It was a dreadful time. Politicians did not want to be associated with the disease. Hospitals resisted admitting victims, and when an AIDS victim died, some health-care workers would place the body in a black garbage bag. Funeral homes refused to accept the corpses. “How to Survive a Plague” follows the drama with the immediacy of the video shot at the time, and some of its most fascinating scenes involve scientists from drug companies such as Merck explaining the slow growth of knowledge about the nature of the disease.

We grow familiar with the names and faces of many of the leaders in the movement. Some look directly into the camera and say they expect to die of the disease. Some are correct. The most heartbreaking scene shows survivors of the dead reaching through fence railings to scatter their ashes on the White House lawn, where presumably they still rest.