Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale mesmerized its readers with vivid descriptions of what a black woman wants in her man, and how hard it is to find it. Women loved it; men were not so thrilled. A friend of mine suggested that the male version of Waiting to Exhale would be much shorter: “What I’m looking for in a woman is someone who’s great in bed, and then turns into a six-pack and a pizza.” That is, of course, exactly the problem: The women in Waiting to Exhale are tired of being treated as disposable commodities by men who will tell them anything before sex and have nothing to say afterward.

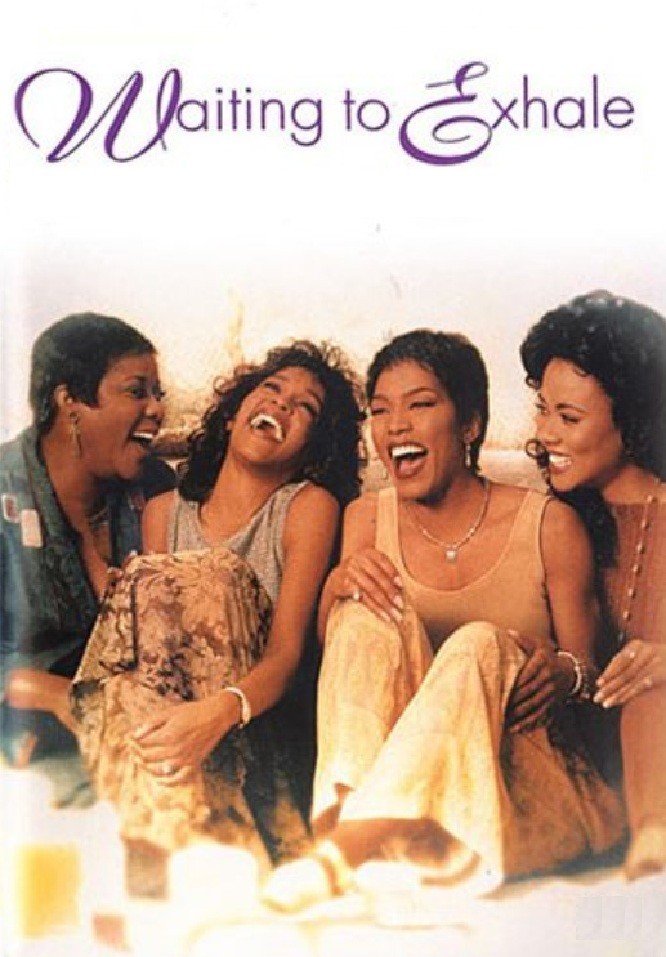

As the movie version opens, broadcast executive Savannah (Whitney Houston) is driving from Denver, where there are apparently no men worth having, to Phoenix, where she hopes there are. Soon she’s playing hostess in her new home to a married man who has been saying for years he’s about to leave his wife. Also in Phoenix are her three good girlfriends: Bernadine (Angela Bassett), whose husband is about to leave her for his white secretary; Gloria (Loretta Devine), who has centered her life around her son, putting on pounds in the meantime, and Robin (Lela Rochon), successful in business but not in love.

During the course of “Waiting to Exhale,” all of these women will either find what they’re looking for, or learn to look for something better. And they’ll do it with dialogue, wardrobes and settings that owe a lot to soap opera: These are not real women so much as fictional creations carefully designed to embody dreams and desires. Many of the women in the audience would be happy to be like any of these women, man or no man.

The cast listing includes a lot of men, who pop up and disappear like ducks in a shooting gallery. Savannah may always have Kenneth (Dennis Haysbert) in her life; he flies in several times a year, telling suave lies to his wife on a cellular phone while promising Savannah that a divorce is imminent.

Bernadine has worked for years in her husband’s business, only to have him leave her for his secretary, “the only woman I’ve ever loved.” Bernadine goes ballistic, throwing his clothes into his car and setting it on fire. (“Would it be better if she were black?” her husband asks. “No – it would be better if you were black!”) Later in the film, in a touching sequence, she finds a soul mate in a man whose wife is dying; the actor, who is not billed in the credits, will be a pleasant surprise.

Gloria is still a fine-looking woman, despite her extra pounds, but has centered her life on her son, Tarik (Donald Adeosun Faison), ever since her divorce. Now she’s in a state of quiet panic as he prepares to leave for a year in Europe. Then a single man (Gregory Hines) moves in across the street, and likes “a little meat on a woman,” and furthermore is a homebody and handyman. (Hines is never seen without a screwdriver or a broken chair; why is it that everything in a handyman’s house needs fixing?) Robin is successful in business, but maybe that intimidates men; the movie has a sad-funny sex scene in which the chubby Michael (Wendell Pierce) makes love badly (“Say my name! Say my name!”), but then turns into an expert at pillow talk. Then there’s Troy (Mykelti Williamson), whom the other girlfriends can see through, although Robin tries to kid herself he’s not a cocaine addict with no money and a habit of stealing anything not nailed down. And there is also Russell (Leon), the handsome guy she’s addicted to even though she knows better.

All of these women and all of their stories have been assembled into a screenplay by McMillan and Ron Bass. He also wrote “The Joy Luck Club,” another film that interlocked the stories of four women, but if that one was high drama, this film is middlebrow, in which the women face not war, famine and firing squads, but cheaters, liars, dopers and guys who look fine but turn out to be gay.

This is a debut directing job by Forest Whitaker, and somehow the tone of the film resembles his own acting: measured, serene, confident. I am not sure that is always the right tone, however. There are times when the material needs more sharpness, harder edges and bitter satire instead of bemused observation.

“Waiting to Exhale” is not really an assault on black men (and men in general), but an escapist fantasy that women in the audience can enjoy by musing, “I wish I had her problems” – and her car, house, wardrobe, figure and men, even wrong men.

On that level, of soap opera and sociological melodrama, however, the movie does work. I was never bored. Occasionally one of the actresses broke out of the mold, as when Bassett coolly dealt with the firemen after torching her husband’s car, and I got a glimpse of the energies that could be unleashed in this material. But for the most part, the movie’s content to be an entertainment with a women’s magazine angle; its patron saint could be Mae West, who wanted more men in her life, and more life in her men.