To the outside world, Violet would seem to have it all. She’s pretty, stylish, and she radiates a quiet confidence. She’s respected and adored in her thriving career as a film production executive in Los Angeles. And she lives with a longtime guy friend—a sweet and handsome screenwriter—in an impossibly cool mid-century modern house in the hills.

But inside her head, she tells herself a different story—or rather, “The Committee” does. The voice purrs menacingly, sadistically, criticizing and questioning every decision and conversation. She’s a pig. She’s in the way. She’s going to fail. She doesn’t belong. And she doesn’t deserve happiness or intimacy.

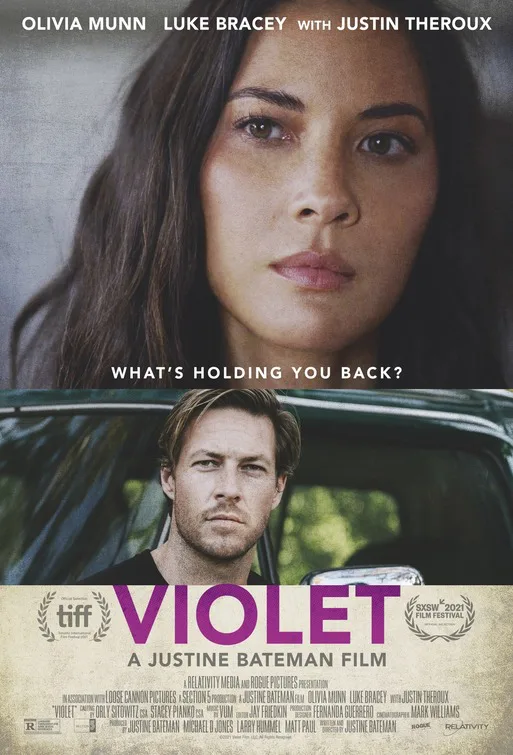

That gaping disparity provides the central conflict within writer/director Justine Bateman’s feature filmmaking debut, “Violet.” Moving from in front of the lens to behind it, the former ‘80s sitcom star clearly has something personal and piercing to say. Her film will surely resonate with so many others who hear their own nagging voices in their heads. And as the title character, Olivia Munn gets the chance to show dramatic abilities we haven’t seen from her previously. But there are so many layers of excessive, incessant style on display in the depiction of Violet’s deep insecurities, they feel like overbearing clutter, preventing Munn’s performance from shining through as powerfully as it should.

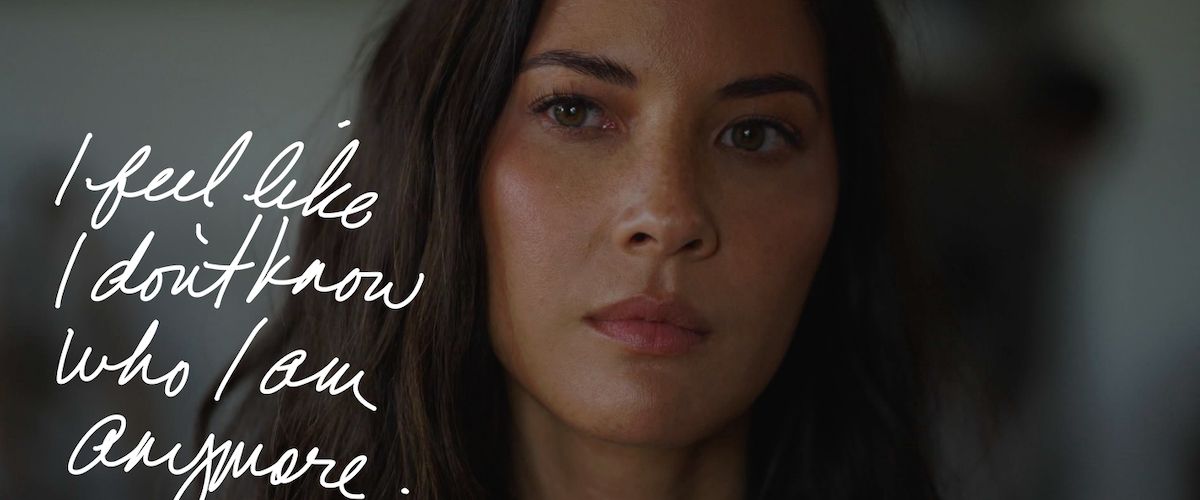

Besides the voice (Justin Theroux, dripping with rich cruelty and sarcasm), Bateman also frequently reveals Violet’s more tender, vulnerable thoughts in the form of white cursive phrases scrawled across the screen. They’re her silent pleas to herself, to the world: “Is there something wrong with me?” “I feel like I don’t know who I am anymore.” “Please stay.” And when the pressure of a certain situation gets to be too much—a work meeting, or drinks with a friend—a low hum builds to a noisy din and a red wash floods the screen, drowning out everything, numbing her pain. “There,” the voice says soothingly. “Isn’t that better?”

As if all that weren’t enough, Bateman consistently cuts in quick snippets of violent and grotesque images throughout. A rapid-fire montage greets and grabs us from the start: car crashes, explosions, glass shattering, animals decaying. This startling artistic choice puts us on edge immediately and signals what kind of hyper-stylized film “Violet” is going to be. But then Bateman goes on to undermine herself by inserting brief flashes of this type of imagery in the middle of conversation to signify Violet’s building mania. Sometimes the cutaways are clunkily literal, such as a boxer getting punched in the face. The ultimate result is that Bateman takes away from the inherent drama or honesty she’d created in that moment. And finally, a flashback to a happier time in Violet’s life—riding her bicycle as a child in Michigan, smiling with the sun and wind in her hair—pops up and plays over and over like a home movie projected on whatever surface is nearby, whether it’s the inside of a tunnel or her bedroom wall. This is another device Bateman leans on too often, and at moments that sometimes seem random.

The first half hour or so of this approach feels exciting, but it soon grows repetitive and tiresome as Violet navigates a series of particularly stressful days, both personally and professionally. Munn subtly indicates the simmering panic of her character’s inner state, and how that anguish contrasts with her placid exterior. She’s fragile and jittery—you can feel her forcing the smiles between air kisses at Hollywood parties. The edgy strings of the score from Vum magnify the tension she’s feeling.

But the supporting players who might have fleshed out her character beyond her anxiety and doubt are drawn superficially at best. Luke Bracey is too good to be true as her hunky roommate and possibly more; it’s unlikely that he’s so perfect, still single, and not a shameless player. Erica Ash is stuck in an archaic trope as Violet’s best friend: a Black woman with no life of her own whose sole purpose seems to be showing up for drinks and listening to this woman’s problems.

And as if tackling and taming the character’s inner demons weren’t enough of an assignment for one movie, Bateman also tries to wedge in a Harvey Weinstein-inspired subplot, with Violet suffering humiliations and indignities from her sleazy, abusive boss (Dennis Boutsikaris), who founded the production company. Bateman has been around this business for most of her life, so there’s clearly a lot of truth in the story she’s telling. If only she’d let it speak for itself.

Now playing in select theaters and available on demand on November 9th.