Wim Wenders filmed “Until the End of the World” in five months in 15 cities in eight countries on four continents, following two lovers played by actors who were reportedly not on speaking terms with one another. I’d love to see the behind-the scenes documentary.

The movie itself, unfortunately, is not as compelling as the tempest that went into its making.

The story takes place in 1999, a future world only a little more shabby, violent and technologically advanced than our own. It lives under the shadow of death, after an Indian nuclear satellite has fallen out of orbit and is spiraling toward the Earth’s surface.

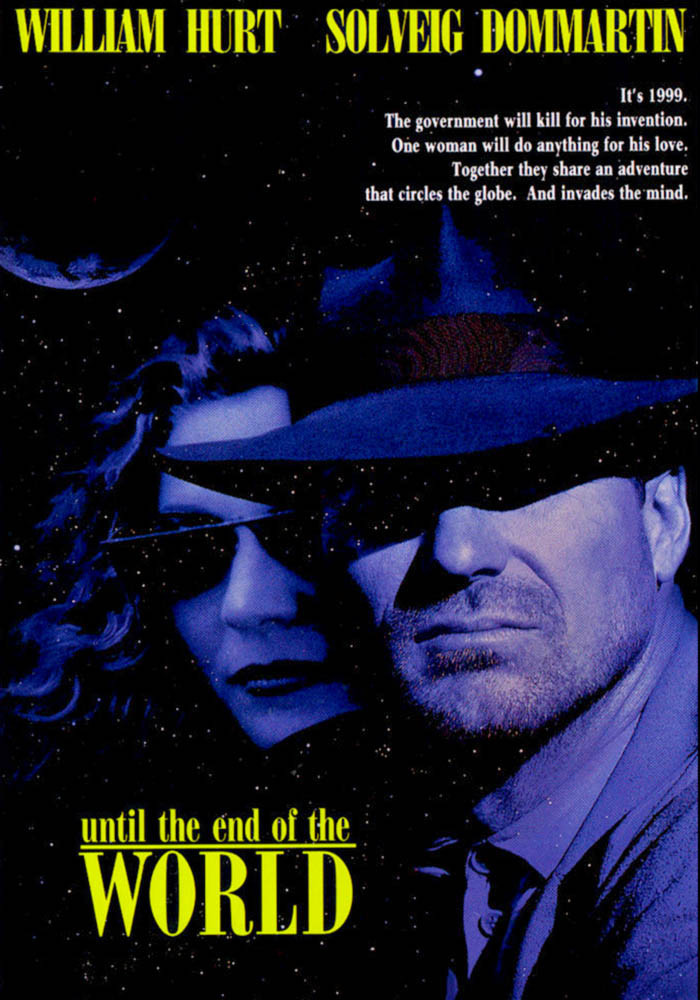

People have put their lives on hold, including a young woman (Solveig Dommartin) who has left her boring British boyfriend for a fling in Venice, and then encounters a mysterious stranger (William Hurt) on the road. He is involved with some dangerous characters who at first seem like important plot factors; later, we suspect Wenders was just throwing in some film noir elements to keep up the interest before getting to his real story, which comes toward the end of this very long film.

Wenders is the master of the road movie. Good road movies, like “Kings of the Road” and “Paris, Texas,” and inexplicable ones, like this one. His screenplays have a tendency to begin with enigmatic figures appearing out of nowhere, and to continue with a series of random events which eventually surrender an insight.

Sometimes that works. “Until the End of the World,” alas, plays like a film that was photographed before it was written, and edited before it was completed; at the end, the insights will mostly have to be our own.

Anyway. As the satellite inexorably spins toward its final resting place, the William Hurt character continues his secret personal mission, which takes him from European locations (Venice, Paris) to San Francisco and points in Asia before finally leading him to that mecca of metaphysical motherlodes, the Australian outback. In love with him and determined to discover what makes him tick, Dommartin tracks him from one destination to the next, while the bad guys bounce around in the background, promising a plot fulfillment they never deliver.

After setting itself up as a road movie crossed with a thriller or whodunit, “Until the End of the World” eventually finds a genre it is comfortable with: the visionary fantasy. In the outback we discover Hurt’s father and mother (official cinematic icons Max von Sydow and Jeanne Moreau) living in an underground laboratory where von Sydow is attempting to provide sight for his blind wife through an array of high-tech, High-Def television inventions. Hurt’s travels are thus explained; he was either (choose one) in search of urgent materials for his father’s experiments, or racing aimlessly around the globe in obedience to Wenders’ creative brainstorm.

A great many scenes in this movie, I am afraid, can be understood only in terms of the way the film was shot. Wenders gathered around him his actors and a core crew of 17 technicians, flew from one city to another, picked up local crews, and shot on the run. His longtime cinematographer, Robby Muller, spoke of trying to maintain a certain visual consistency through framing and lighting, but Wenders was essentially at the mercy of local shooting conditions, and many of the scenes feel as if they were altered to cope with unforeseeable circumstances. There is none of the narrative urgency that would help in drawing us through to the end of the 157 minutes.

At the end, there is, perhaps, a moral to be found. The movie arrives at the Outback, a place where oral traditions have survived for centuries, where the aborigine people tell stories to one another and move in and out of dreamtime. To that place, von Sydow has brought his laboratory, which is like a mad scientist’s vision of future means of communication. The film has already introduced us to picture phones and cars that call their owners by name; now we find technology that allows machines to visualize human dreams. And just when it all looks like it’s about to work, wouldn’t you know the nuclear satellite fries half the world’s computer chips? The moral is clear: We humans should remain centered in our traditional storytelling skills, and not allow technology to dictate the way we communicate and dream. It is a wise lesson; one, indeed, this film might have profited from.