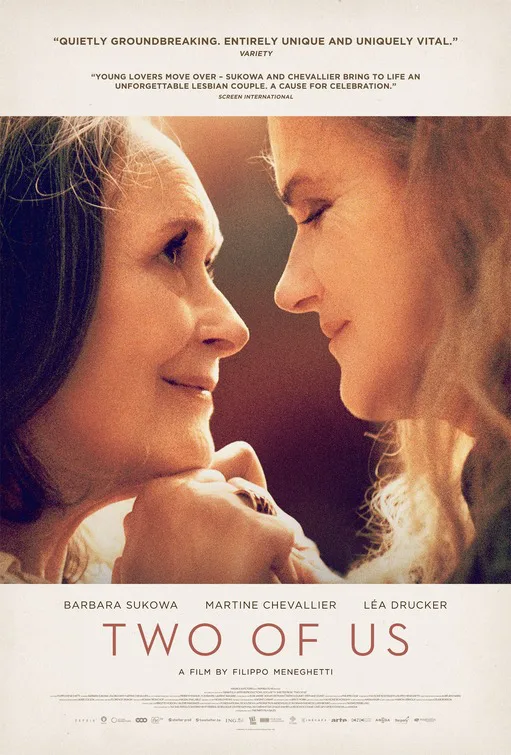

“Two of Us” chooses an odd but successful way to tell its love story. There is nothing strange about the romance itself, and some of the plot points in the screenplay by director Filippo Meneghetti and Malysone Bovorasmy will be familiar. But the beats play in a suspense thriller’s register, creating a heightened tension that is often unnerving. We are living the story through the eyes of a lover desperate to reconnect with her beloved, and her feelings of desperation, concern and fear bleed directly into the frame. Some of the actions taken by Nina Dorn (Barbara Sukowa) to be by her lover Madeleine’s (Martine Chevallier) side barely skirt pitch black comedy or even farce. Yet, we’re with her all the way even as we’re thinking “what is she doing?”

I shall tread cautiously on plot details. Madeleine and Nina are older women passionately in love. By itself, this is refreshing, as we rarely see this type of randy lust and the joy of togetherness on anyone past a certain age onscreen. The two women live opposite one another, with both apartments serving as love nests. After much time in this arrangement, the duo are ready to consolidate their living quarters by selling their respective apartments and relocating from France to Rome, the place where they first met. Nina appears to be a free agent, but Madeleine is a widow with two grown children, Anne (Léa Drucker from “Custody”) and Frédéric (Jérôme Varanfrain), and a grandson Théo (Augustin Reyes). None of them know about Nina. To them, she is simply Madame Dorn from across the hall.

While Anne is close to her mother, Frédéric is distant, cold, and often mean to Madeleine. He accuses her of cheating on the father he considers a saint. Whether he has proof is never explicitly declared; the notion alone is enough to make him antagonistic enough to ruin Madeleine’s birthday party. This event was supposed to coincide with Madeleine’s decision to out her relationship with Nina and reveal their subsequent relocation. However, Frédéric’s animosity makes it difficult for her to deliver the news, and worse, gives her second thoughts about the move altogether. Meneghetti and cinematographer Aurélien Marra shoot the scene where Nina realizes Madeleine has no intention of relocating by having the latter witness the revelation through a window behind her. It looks and feels lifted from an espionage thriller.

This type of disappointing news usually serves as that plot element in every romance where the relationship is temporarily rent asunder. However, “Two of Us” has a much bigger bombshell of a plot development to drop immediately after its customary blow-up scene. I will not reveal what it is, except to say this type of separation would prove insurmountable in a less hopeful movie. Suddenly, decisions are being made against the lovers’ wills by people whose best intentions blind them to the palpable, aching desires of two women who clearly want to be together.

This delicate balance of romance and discomfort would collapse without the fine work by Sukowa and Chevallier. Chevallier has the harder role, because much of it is reactionary and restricted by the mechanics of the plot. Madeleine’s anxiety about publicly being in love with another woman gives way to an even more anxious need to be by her side. Sukowa complements her co-star with a steely determination that is at times equally fearless and dangerous. Nina makes a few decisions that will come back to bite her in ironic ways, but there’s no denying her commitment to the love of her life.

“Two of Us” toys with the viewer like a cat with a mouse. It knows we’re watching, and it acknowledges that voyeurism by focusing on peepholes and windows, both of which are constantly providing information. There’s also some pointed commentary about how children think they have the wisdom and the right to deny the wishes of their older parents. Most noticeably, the film is conscious of the audience’s presumptions about what will happen to these women, presumptions carved into us by the tragic gay and lesbian character tropes that influenced so many films of the past. Everything is wound as tightly as a good thriller demands, though this technically isn’t one. The story of Madeleine and Nina ends ambiguously from a plot perspective, but the emotions in that final scene are incontrovertible.