Watching “Custody” I was reminded of one of Roger’s tenets: “It’s not what a movie is about, it’s how it is about it.” Writer/director Xavier Legrand’s feature length debut is about a bitter custody battle, but he has chosen to execute his plot as a quiet, brutally relentless psychological thriller. “Custody” filters the majority of its terror through Julien Besson (Thomas Gloria), the 10-year-old boy at the center of his parents’ vicious legal struggle. This device never feels exploitative, because as any child of divorce will tell you, the dissolution of one’s parental unit is traumatic even when the split is amicable. And this is not an amicable split.

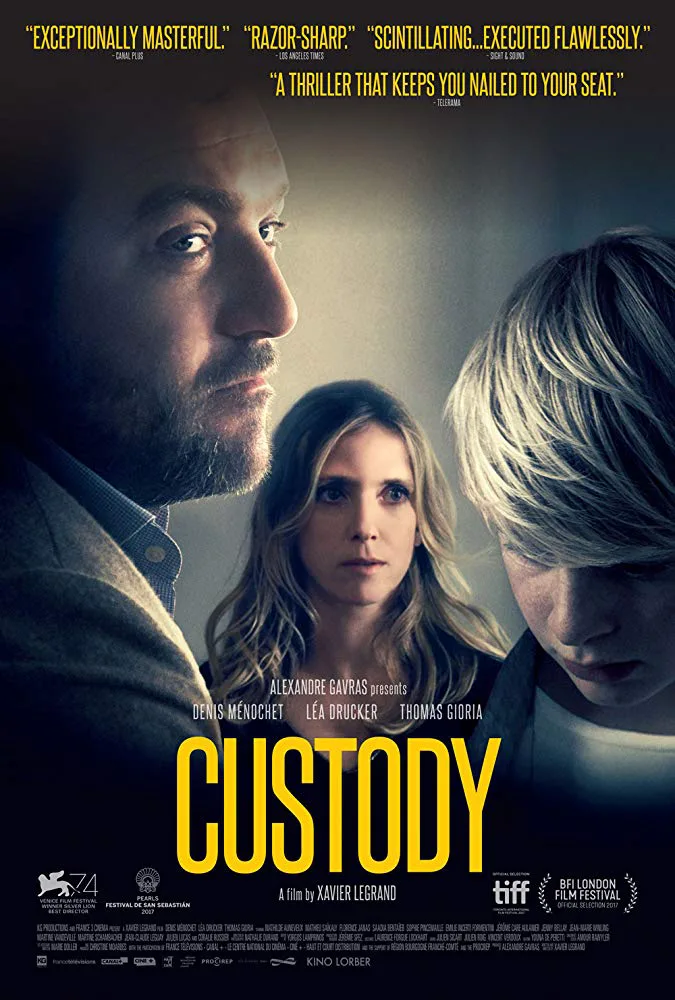

In the film’s opening scene, Antoine Besson (Denis Ménochet) and his lawyer are at a hearing to seek joint custody of Julien. His soon-to-be-ex-wife, Miriam (Léa Drucker) strongly objects to this request, citing Antoine’s history of violence against her and their older daughter Joséphine (Mathilde Auneveux). Joséphine wants nothing to do with her father, and since she is of age, Antoine cannot influence her decisions. Julien is another story altogether—he cannot legally make an adult decision—though he does express through a letter that he also wants nothing to do with Antoine.

Legrand shoots this sequence in a documentary-like fashion, moving back and forth between Miriam and Antoine while spoken legalese flies through the air. As their court-appointed arbitrator sizes up both sides of the equation, so does the camera, though it’s far too early for the film to tip its hand, Instead, Legrand lets the scene play out far longer than one anticipates, raising doubt all around. Is Antoine really violent, or is he just an exasperated father who’s correct in his accusation that his wife has turned his children against him? Is this going to evolve into “Kramer vs. Kramer” or something more sinister? Even when Miriam’s lawyer presents evidence of an injury Joséphine suffered because of Antoine, we’re not sure whether his far less damning explanation isn’t credible.

Once Antoine wins partial custody, however, we start to realize that he is not the concerned father he appeared to be. He is a monster, though not the one-dimensional kind that often fills the villainous role. Antoine is a man in pain about his impending divorce, and while that’s by no means a forgivable excuse, it adds a bit of uncomfortable complexity. Ménochet towers over his fellow actors, and even when seemingly calm, Antoine sucks all the oxygen out of a room when he enters. Legrand’s camera follows suit, squeezing Antoine and Julien into confined spaces like cars, constricting the frame until we feel as trapped as his characters do.

As the audience stand-in, Gloria is a huge part of what makes these scenes successful; he has a very expressive face that often fills the screen in silence while his body telegraphs the sad resignation of one who feels helpless. Julien exists under constant emotional duress in Antoine’s world, and this thriller does not offer him much comfort. Yet Julien also has a fierce determination to protect his mother at all costs, which is an unfair burden for him to carry but is also quite realistic in domestically violent situations. Julien’s one act of defiance in service to sparing his mother results in a terrifying chase that is masterful in its suspense. That it ends with psychological violence rather than physical altercation makes it no less harrowing.

As Miriam, Drucker has the most complicated role in “Custody.” Like Julien, she physically carries a sense of resignation on her person, but she has a far more adult understanding of how the system has failed her and her kids. Her actions are subtle but they speak volumes; Legrand leaves out most of the backstory but we can infer that she was left to her own devices because the police were of little use to her when she was married. “Custody” gives her two big, distinctly different dialogue scenes with Antoine alone, and though she has the quieter performance in each, she holds her own by showing the self-preservation strategies Miriam employs in a valiant attempt to emerge unscathed.

Before he goes full-tilt thriller in the film’s climax, Legrand keeps the viewer off guard by giving certain scenes an unusual pacing or mixing together two scenes that are tonally different. The former works in a long, bathroom scene where a character takes a pregnancy test and responds to the results. The latter, however, results in a way too on-the-nose use of Josephine singing Ike and Tina Turner’s classic cover of “Proud Mary” intercut with the threat of spousal abuse.

“Custody” plays like a more humanistic Michael Haneke film. It’s emotionally bruising but not without some glimmer of hope, personified here by a close-up of the preternaturally kind face of a 911 dispatcher. Legrand took home directing honors from the Venice Film Festival and deservedly so. I look forward to what the director does next. And while “Custody” is not particularly violent, I must warn that its subject matter has the capability to be quite triggering. So please exercise caution.