Luis Buñuel’s “Tristana” is a haunting study of a human relationship in which the power changes hands. Power over human lives is a lifelong theme of Buñuel, that most sadomasochistic of directors, and “Tristana” is his most explicit study of the subject. Not his best, but his most explicit.

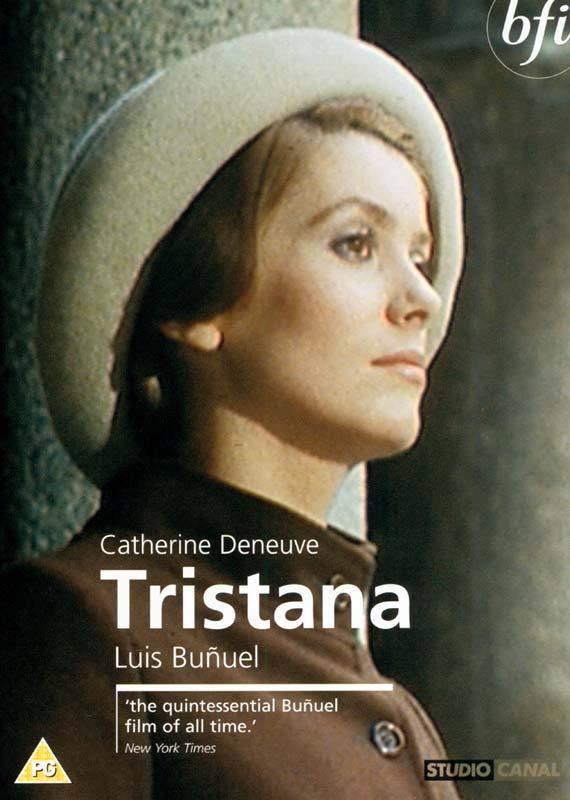

Consider. Don Lope, a feisty middle-aged intellectual and atheist, sees his chance when the beautiful young Tristana (Catherine Deneuve) is orphaned. As the girl’s guardian, he takes her into his household and (in what seems like no time at all) into his bed. While ravishing her, he excuses himself by rationalizing that she’d fare worse on the streets.

The girl is repelled by the old man’s sexual advances, and that provides the key to her character later in the film. She falls in love with a handsome young artist who eventually takes her away and marries her. But then she develops a tumor and her leg must be amputated; she decides to leave the artist and come back again to Don Lope’s household.

All that’s gone before has been preparation for what happens now, as Tristana has revenge on the man who took her virginity. He is older now, weaker, and has been reduced to playing cards with priests. He does it not because he’s lost his atheism, but because he craves their company (and they humor him with an eye to gaining his inheritance for the church). Tristana becomes the dominant personality in the household.

Handled by an ordinary director, or even by a great director with no sympathy for the material, this story could have been embarrassingly melodramatic. I was about to say it could have been disgusting — but, of course, it is disgusting, and that was Buñuel’s purpose. The subject matter came out of his own lifelong obsessions. His favorite subjects were sadomasochism and anticlericalism ever since his first movie with Salvador Dali, “Un Chien Andalou” (1928), and in the late flowering of his work in his 70s he became undoubtedly the dirtiest old man of genius the cinema has ever produced.

Certain of his scenes have an almost hypnotic power, because Buñuel himself finds their images so fascinating. The vision of Don Lope’s amputated head, used as a clapper on a church bell, reportedly refers to a recurring dream Buñuel (that lifelong atheist) has about himself. The long scene where Don Lope plays cards while the one-legged Tristana walks back and forth on her crutches in the upstairs hallway also has a dreamlike quality.

Again, Buñuel introduces a mute young servant into the household, and Tristana tantalizes him mercilessly. He desires her; she repels him coldly, only to reveal herself to him when she is on her balcony and he in the garden. He draws back quickly into the shrubbery. Buñuel’s Freudianism is so explicit as to be almost embarrassing, but you never laugh, because he takes it so seriously. That’s why his films work; because they’re himself, they’re personal. Buñuel is in control of every shot and every scene, and he is having at our subconscious like a surgeon.

A few great directors have the ability to draw us into their dream world, into their personalities and obsessions and fascinate us with them for a short time. This is the highest level of escapism the movies can provide for us — just as our elementary identification with a hero or a heroine was the lowest. As children, we went to Saturday matinees and for an afternoon we were cowboys and Indians. As adults, there are more intellectual routes to escapism. A powerful director like Buñuel (or Bergman, Fellini, Hitchcock or Satyajit Ray) can open up his mind to us, the way an actress can open up her eyes. It is an experience worth having.