On my first trip to Ireland, in 1967, I was taken to a party after the pubs closed. There were bottles of whiskey and Guinness stout, someone had a concertina, and there was a sing-song. In the bedroom, a couple was making out. Eventually they emerged to join the party, and I noticed that, to my young eyes, they were “old”–in their 40s.

On the way home, I asked my friend McHugh about that, and he explained that they had been engaged for 15 years, that they were putting off marriage until the man made more money, and until “family matters” got sorted out. Necking at parties was undoubtedly the extent of their sex lives, since intercourse before marriage was a mortal sin. I said I thought it was sad that two middle-aged people, who had loved each other since they were young, had put their lives on hold. “Welcome to Ireland,” he said.

It is not like that anymore in Ireland, where some of the old customs have died with startling speed. But that is the Ireland remembered in “This Is My Father,” a film about lives ruled by guilt, fear, prejudice and dour family pride. For every cheerful Irish comedy about free spirits with quick wits, there is a story like this one, about characters sitting in dark rooms, ruminating on old grudges and fresh resentments, and using the rules of the church, when convenient, as justification for their own spites and dreads.

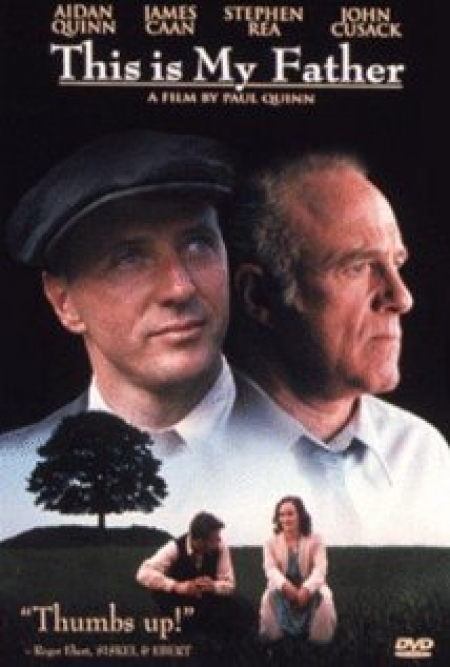

The movie is said to be based on a true family story and has been made by Chicago’s Quinn brothers. Aidan Quinn stars as an orphaned tenant farmer who falls in love with the daughter of the woman who owns the land he works. Paul Quinn directs. Declan Quinn, the cinematographer, is known for work such as “Leaving Las Vegas.” It is so much a family project that there is even a role for a friend, John Cusack, who drops in out of the sky in a small plane, lands on the beach and figures in a scene as charming as it is irrelevant.

The heart of the story involves Kieran O’Day (Aidan Quinn) and Fiona Flynn (Moya Farrelly), who fall passionately in love in 1939. He is an orphan, being reared by a tenant couple named the Maneys (Donal Donnelly and Maria McDermottroe) on land owned by Fiona’s mother, Mary (Gina Moxley). The mother has fierce pride, not improved by a drinking problem and looks down on her neighbors. Of course she opposes a liaison between her daughter and a tenant.

This story is told in flashback. In the present day, we meet a sad, tired high school teacher (James Caan) whose mother is dying and whose life is going nowhere. He determines to go back to Ireland and search for his roots. In the village where his mother came from, he finds an old gypsy woman (Moira Deady) who remembers with perfect clarity everything that happened in 1939 and triggers the flashbacks. The modern story is almost not essential (we forget Caan in the midst of the flashback), but it does trigger a happy ending in which much is explained.

The key element in the romance between Kieran and Fiona, and the one that reminded me of my first visit to Ireland, is the way their sex lives are ruled by others, whose own real motives are masked under the cover of church law. Mrs. Flynn is spiteful, mean and bitter, or she would find a way for her daughter to be happy. Kieran’s love is all the more poignant because he sincerely believes himself to be an occasion of sin for Fiona and castigates himself for endangering her immortal soul.

Fiona’s mother pays lip service to the church, but her real motives are fueled by class prejudice and social climbing, and there is a cruel moment when she accuses Kieran of molesting her daughter. She also threatens the Maneys, who have reared him, with the loss of their land and livelihood. One scene that rings true to life is the way the village policemen, negotiating a tricky path between the laws of this world and the next, give Kieran broad hints about their plans for eventually arresting him–should he still be in the vicinity, of course. Sensibly, he is not, but the cost of his freedom is his happiness, and that price is underlined by a message that the Caan character discovers, and delivers several decades too late.

I believe “This Is My Father” is indeed based on true family stories (or legends, which are the same thing), because it insists on details that are more important to the narrator than to the listener. The entire construction of the Caan character, for example, is explained no doubt by a relative’s visit back to the old country. The story might have been simpler, sadder and sweeter if it had taken place entirely in 1939–but like all stories, it belongs to the teller, not the subject.