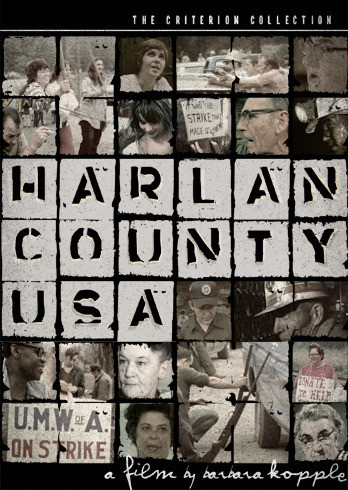

The film retains all of its power, in the story of a miners’ strike in Kentucky where the company employed armed goons to escort scabs into the mines, and the most effective picketers were the miners’ wives — articulate, indominable, courageous. It contains a famous scene where guns are fired at the strikers in the darkness before dawn, and Kopple and her cameraman are knocked down and beaten.

“I found out later that they planned to kill us that day,” Kopple said later, in a discussion I chaired at the Filmmakers’ Lodge. “They wanted to knock us out because they didn’t want a record of what was happening.” But her cinematographer, Hart Perry, got an unforgettable shot of an armed company employee driving past in his pickup, and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

Kopple brought some friends along to the festival. Foremost among them was Hazel Dickens, a miner’s wife and sister, now 69, who wrote songs for the movie and led the room in singing “Which Side Are You On?” Kopple also shared the stage with Utah miners who are currently on strike; although the national average pay for coal miners is $15 to $16 an hour, these workers — who are striking for a union contract — are paid $7 for the backbreaking and dangerous work.

Using a translator, the Spanish-speaking miners told their story. One detail struck me with curious strength. A miner complained that his foreman demanded he give him a bottle of Gatorade every day as sort of a job tax. It is the small scale of the bribe that hit me, demonstrating how desperately poor these workers are. Work it out, and the Gatorade represents 10 percent of a daily wage.

Kopple and Perry spent 18 months in Harlan County, filming what happened as it happened. Her editor, Nancy Baker, who was also onstage, took hundreds of hours of footage and brought it together with power and clarity. I asked Kopple what she thought about other styles of documentaries, like Michael Moore’s first-person adventures, or the Oscar-nominated “Story of the Weeping Camel,” which is scripted and has people who portray themselves, but is not a direct record of their daily lives.

“I accept any and all kinds of documentaries,” she said. ” ‘Harlan County’ came out of the tradition of Albert Maysles and Leacock and Pennebaker, documentarians who went somewhere and stayed there and watched and listened and made a record of what happened. That is one approach. There are others, just as valid. All that matters is making a good film.”

Reprinted from Ebert’s 2005 Sundance coverage.