Many of you may remember when Donald Trump was elected back in 2016, that more than a few vocal opponents of his presidency looked for a silver lining in the arts. Punk rock protest would come back, stronger than ever! Many great satirical works would take the administration down … somehow! And so on.

Well, that didn’t really work out at all.

In 2020, as the COVID crisis grew more dire, there was not quite as much speculation as to whether it would produce world-changing art; the whole thing was just too frightening and depressing to encourage such speculation.

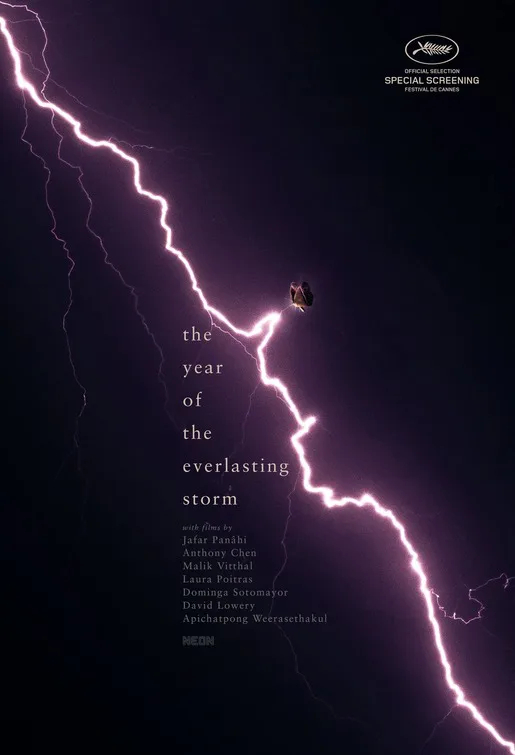

But COVID-pertinent art is being made; this omnibus film is a new and prominent example. Seven shorts from seven directors, and a perhaps predictably mixed bag in terms of artistic success and failure.

It begins in Tehran, with a warm, slightly predictable, but mostly winning piece of autofiction from Jafar Panahi (“Crimson Gold,” “This is not a Film”). The short depicts a visit from his mother-in-law, who turns up at the apartment he shares with his wife in a protective jumpsuit and face shield, so completely covered up that the couple initially takes her for an essential worker of some kind. Once inside, the older woman is skittish—not because of COVID, but because of the couple’s pet iguana, named Iggy. The senior upbraids the Panahis for allowing her grandkids to live abroad—one of them, in a Facetime call, encourages Grandma to engage with Iggy—and the trio quietly meditate on mortality. The anecdote ends with a sweet note of reconciliation.

“The Breakaway,” from Anthony Chen, depicts a living situation almost universal: that of a couple (Zhou Dongyu and Zhang Yu) and their young child trying to work and live in cramped quarters without driving themselves or each other insane. As is frequently the case, the male partner is the more troublesome, dropping the ball on money matters and saying “It’s just a dog” when his partner expresses sadness over the death of a childhood pet she hasn’t seen in a while. It’s a strong, coherent piece of work. But, not to be uncharitable, it may tend to elicit a “tell me something I don’t know” response from some viewers. That’s also the case with “Sin Titula,” the contribution from Chile’s Dominga Sotomayor, a portrait of a woman in isolation.

From California, the contribution from Malik Vitthal, a semi-documentary look at the life of a single dad whose longtime fight to gain custody of his three children was presented with a curveball by the virus, mixes animation with phone videos to create a fresh, bracing anecdote. The documentarian Laura Poitras offers a glimpse into her collaboration with the group Forensic Architecture, investigating the NSO Group, a company that develops and sells cyber weaponry—surveillance tools for surveillance states, except nowadays every state is a surveillance state of some kind. The urgency of the information presented verbally in this segment is frequently undercut by the visuals, reproducing Zoom gallery views in which the participants (journalists and activists for the most part) look cushily comfortable and at times bored. In one shot, Poitras blows up a quadrant of the gallery so you’re looking at a bearded guy propping up his head with a closed hand like he can barely be bothered. Why am I seeing this, one is likely to ask. I found myself musing that this would be footage for Godard to deconstruct, “Letter to Jane” style.

The final two segments are the strongest: David Lowery’s spooky, enigmatic “Dig Up My Darling,” in which an older woman, rooting around a garage, discovers a cache of letters postdated from 1926, when a flu epidemic catastrophized New Orleans. Upon reading them, she makes a side trip from the unspecified, nomadic, but definitely COVID-necessitated journey she had been on. Then there’s Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s frankly startling “Night Colonies,” in which no humans appear. Rather, the stars here are various insects and an array of fluorescent lights. On the soundtrack, eventually, snatches of audio events from pro-democracy protests in Bangkok. A poem presented on screen in the short’s opening minutes gives the feature as a whole its title.

There are consolations to be found here, and some things more crucial. “The Year of the Everlasting Storm” is definitely a noteworthy achievement in anti-escapism, which the current cinema could certainly always use more of.

Now playing in select theaters.