The success of “Crimson Gold” depends to an intriguing degree on the performance of its leading actor, a large, phlegmatic man who embodies the rule that an object at rest will stay at rest until some other force sets it into motion. The character, named Hussein and played by Hussein Emadeddin, is a pizza deliveryman in Tehran, Iran, heavy-set, tall, undemonstrative. He sits where he sits as if planted there, and when he rides his scooter around the city streets, he doesn’t lean and dart like most scooter drivers, but seems at one with his machine in implacable motion. When he smokes, he is like an automaton programmed to move the cigarette toward and away from his lips.

He has a friend named Ali (Kamyar Sheissi). We meet Ali for the first time in a tea house, where he produces a purse he has just found. Its contents are disappointing — a broken gold ring. Another man overhears their conversation, assumes they stole the purse and delivers a little lecture on the morality of theft. He believes the rewards should suit the crime; you should not put your targets through a great deal of suffering just to relieve them of pocket change.

Hussein, who is engaged to Ali’s sister, seems an unlikely candidate for marriage. We learn indirectly that he was wounded in the Iraq-Iran war, and Ali refers to his “medication.” Perhaps that accounts for his sphinxlike detachment; he acts as little as it is possible to act and yet, paradoxically, we can’t take our eyes off him.

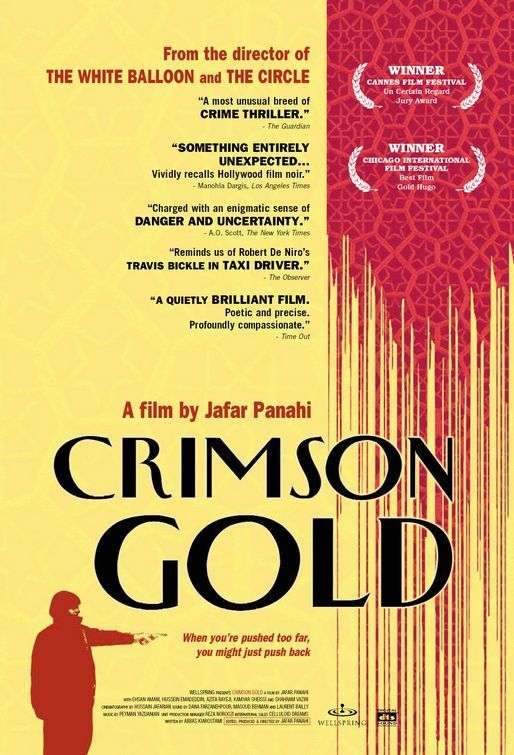

The film uses Hussein and his life as a lens to look at Tehran today. The director, Jafar Panahi, also made “The Circle,” a film showing the impossibility of being a single woman in modern Iran without having a man to explain your status. It was written by Abbas Kiarostami, the best-known Iranian director, and includes his trademark: long, unbroken shots of a character driving somewhere. In this case, it is Hussein on his scooter, sometimes with Ali as a passenger.

Hussein lives a solitary existence in an untidy little flat, venturing out at night to deliver pizzas. One night he delivers a stack of pizzas to the penthouse of an apartment building in a wealthy neighborhood. He is greeted at the door by the occupant (Pourang Nakhayi), who complains that “the women have gone” and he doesn’t need the pizza. But he invites Hussein in, asks him to eat the pizza, and talks obsessively about himself: how his parents lived in the apartment only for a month before moving overseas, how he has just returned to Iran and finds it not organized to his liking, how women are crazy and unpredictable.

Hussein eats steadily and regards him. Later, as the man is on the telephone, he walks around the apartment (he has never been so high up in his life), looks at the skyline, visits a bathroom more luxurious than any he could imagine, dives fully clothed into the swimming pool, and is seen later wrapped in towels.

When he leaves the apartment, he goes directly to a jewelry store that he and Ali had visited twice before. The first time, they wanted to get a price on the gold ring, and were treated rudely and with suspicion by the store owner and guard. Returning, wearing ties and with Ali’s sister along, they said they were shopping for a wedding ring — but were treated rudely again; it is a high-end store and they look like low-end people.

After he leaves the high-rise apartment, Hussein returns to the store. We already know much of what will happen now, because “Crimson Gold” opens with a version of the same scene it closed with. But I will not discuss the opening (and closing) because they proceed with a kind of implacable logic. What seems impulsive and reckless at the beginning of the film takes on a certain logic after we have spent some time in Hussein’s company. In his case, still waters run deep and cold. He has been still and implacable for the entire film, but now we understand he was not frozen, but waiting.

Note: In real life, Hussein Emadeddin, a non-actor, is a paranoid schizophrenic. Having learned this information, I felt obliged to share it with you, but the film does not refer to the disease; perhaps Jafar Panahi found that Emadeddin’s demeanor, whatever its source, provided the kind of detachment he needed for his character. Hussein (the character) is doubly effective because he does not seem to be an active participant in the story, but an observer carried along by the currents of chance.