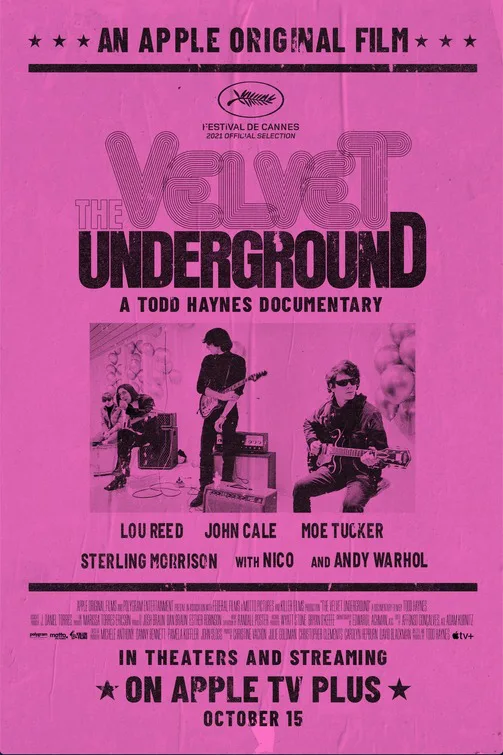

The art-rock-noise band The Velvet Underground destroyed and remade listeners’ received wisdom about what rock-‘n’-roll could be. It is elating and right that Todd Haynes’ new film about them would do the same for music documentaries.

Be aware, though, that viewers who come into Haynes’ two-hour movie “The Velvet Underground” looking for a primer on the band, Lou Reed, John Cale, Maureen “Mo” Tucker, Nico, Andy Warhol, Mary Woronov, The Factory, and other famous names and locations may find the experience disorienting. Despite the presence of traditional documentary elements, and a mostly linear story that pulls you through about 20 years’ of cultural history, Haynes and his collaborators make the experience feel new and surprising, assembling the component parts with an eye towards making not just a movie, but an experience—something that you feel, as you might feel the drums during a live music performances: in your gut.

Interview subjects who were present at the time—including Velvet co-founder Cale, a Welsh classical musician; Mo Tucker, their signature drummer; actress and painter Woronov; my colleague Amy Taubin, a veteran film critic; and the late Anthology Film Archives co-founder Jonas Mekas, who died not long after his interview—offer commentary and insight, alternating between taking a detached “long view” of things and plunging us into the middle of it all.

Like another great 2021 music documentary, Questlove’s “Summer of Soul,” this movie appears to deliberately adopt the structure of a mid-twentieth century vinyl album—the kind with songs arranged in tracks that are meant to be experienced in a linear way, first Side A and then Side B, straight through, without stopping. Every few minutes, the editing shifts emphasis so that you’re not just switching musical tracks but intellectual tracks: as in railroads, as in “one-track mind,” or “train of thought.”

Under Haynes’ supervision, cutters Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz let the material flow and change direction, twist back, feed on itself recursively, digress, then return to the main point. Singer songwriter Jonathan Richman dissects the band’s musical choices, imitating both Reed’s vocals and Cale’s background drones, blending the enthusiasm of a fan with the rigor of a working musician. Woronov hilariously contrasts the acidic, bleak 1960s New York version of the counterculture with its California equivalent, ridiculing peace, love, and flower power as political cop-outs. Taubin critiques the sexism of the Factory, where women, including lead singer Nico, were prized for their looks over all else.

The effect is less like sitting in a classroom and having facts laid out for you than listening to a semi-improvised Velvet Underground jam while perusing coffee table books or pictorial websites about the band, and pondering connections between the music that the band was making and the events that were unfolding in the world around them. It’s a feedback loop of information, creating a cinematic equivalent of that hypnotic drone that flows beneath so many of the Velvet Underground’s songs, and that Cale insightfully tells us was modeled on the “60-cycle hum” of appliances and machines from that period in history, the sonic undercurrent of modern life.

There’s another thing happening here, involving overlapping dialogue and music cues and split-screen images, and it’s just as fascinating: Haynes seems to be trying to find a streaming-era equivalent to the multimedia sound-and-light shows that Warhol and his friends and “discoveries” used to stage around New York in the ’60s — the music/dance/poetry/cinema “happenings” comprised of the Velvets performing a song, films being projected on the musicians, selected audience members operating spotlights, and so on. Haynes and cinematographer Ed Lachman shoot present-day interviews in the manner of Warhol’s “close-up” films, with even-toned lighting and a solid-colored background, in an old-fashioned “academy ratio” image that’s closer to a square than a rectangle. The style feels both classical and fresh, subtly channeling footage taken by Warhol and other Factory-adjacent filmmakers at the time, some of which is featured here as well.

The various materials are arranged in split-screen compositions that evoke Warhol’s “Chelsea Girls,” a quasi-documentary “experience” ideally presented in a theater where two 16mm film projectors run simultaneously, casting images side-by-side as soundtracks overlap to create a dissonant soup of dialogue, music, and noise. During the opening section of the film, half of the split-screen image is an unnerving Warhol closeup of young Lou Reed staring blankly for minutes on end.

Sometimes the adjacent split-screen panel will be filled up with images of whatever an expert witness is telling you about in voice-over. Other times you might be looking at out-of-focus images of Manhattan taken from a moving vehicle, or the psychedelic sunbursts that occur when a reel of film runs out while passing through a camera’s gate, or three or six or twelve related images flickering in a grid.

In addition to new and old material that’s directly relevant to the band (including early “music video” footage, and shots of them gallivanting in New York, Los Angeles and other locales), you also see images from filmmakers who operated contemporaneously with the Factory or inspired them, from Warhol’s time-expanding kissing films and snippets of his epic static shot “Empire” to fragments of Kenneth Anger’s “Scorpio Rising.” Squarish images presented solo are often pushed to the extreme left- or right-hand side of the rectangular frame, making you aware of the blackness that isn’t the image. This never feels like an affectation because so many of the expert witnesses, Cale specifically, stress that the Velvet Underground was unique because it valued negative space, and was about taking things away rather than adding them.

Sound and image don’t merely work together but at cross-purposes, creating metaphors, arguments and vibes. Even when Haynes (who treated some of the same themes fictionally in his music drama “Velvet Goldmine“) is being sneakily conventional, verging on a public television-style, “let’s all appreciate this incredible thing that happened” mode, you always feel as if you’re being immersed in a kaleidoscope of impressions, associations and anecdotes. They swirl across the screen like the polka-dot lights that used to wash over the band during live performances at the Factory, to the annoyance of Reed and Cale, who wanted their music to be central to the experience, even though they knew intellectually that it was one part of a bigger vision.

The movie is Godardian, as in Jean-Luc, but it’s also Warholian, and Haynesian. If you’re in the right frame of mind, it’s hypnotizing, brain-expanding, and just plain fun. And if it’s not your thing, it’s fine; part of the Factory philosophy was that you should make art for yourself, first and foremost, and not get too hung up on what others think. (“I don’t have to listen to this shit,” a Los Angeles studio engineer told the band when they were recording 1968’s White Light/White Heat. “I’ll put it on record, and I’m leaving. When you’re done, come and get me.”)

This is a dazzling film—not just one of Haynes’ best, but possibly the one that his whole career, with its self-aware generic and formal and historical experiments, has been building toward. I’m jealous of anyone who experiences it for the first time projected on a big screen, with booming sound, because that’s how it should be seen. It’s a spectacle as well as an account of a time and place. It makes you think about what a documentary is, and what film can do, even as it does the things that you want and need.

In theaters today and on Apple TV+ on Friday, October 15th.