Jim Hemphill’s “The Trouble with the Truth” is a pleasant surprise that gets better as the movie unfolds. A divorced couple meets for dinner after their daughter announces her engagement. In the course of this very long meal, they discuss everything we would expect from divorcees wrestling with their feelings. Structured as a single long conversation, it has been compared to Louis Malle’s “My Dinner With Andre.” and Richard Linklater’s “Before Sunrise” and “Before Sunset.” It is a very small movie with very deep feelings.

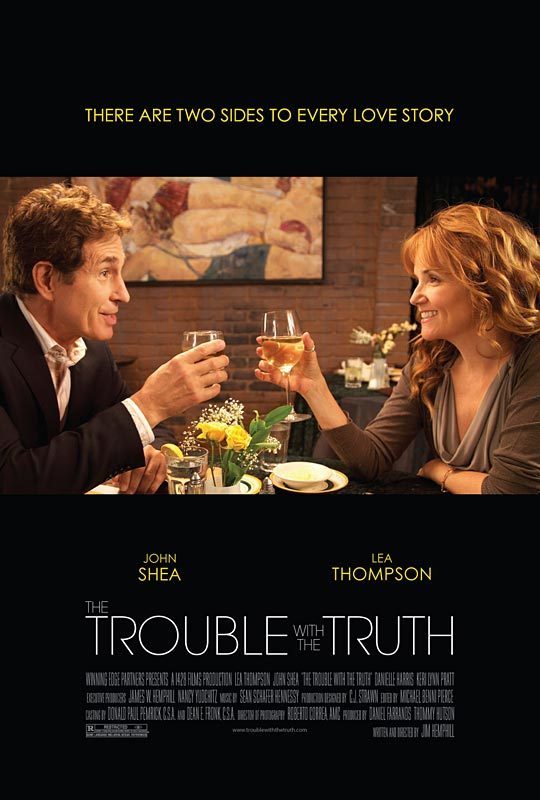

Robert (John Shea) is a struggling jazz musician. His is a disappointing career, save for a few highlights that probably hold more meaning for him than for the superstars, like Miles Davis, he shared them with. Emily (Lea Thompson) is a successful novelist, preparing to write her next big book. Now that their sole child from their 14-year marriage, Jenny (Danielle Harris), is getting married, they find the chance and willingness to meet. There is something intimate about the long conversation in a dark, elegant restaurant, inviting us to divulge fruits from our secret gardens. How much do we share about ourselves, in such a public setting, knowing that the woman in the next table might be paying attention?

Their marriage did not end amicably. This film has us then wondering when couples are ready for such meetings. When does the fury of a hostile divorce finally cool off, enabling the couple to meet for a quiet dinner, and perhaps reach closure? As necessary as it might be for today’s engaged couples to go through pre-marital counseling, this movie has me thinking that divorcees should go through exit interviews. In this case, it took some ten years for Robert and Emily to be ready. In that decade, they had time to reflect on their marriage, trying to untangle the twisted knots of hidden feelings. They start to confront real answers to those basic questions. What is it that breaks the marriage? Is it the anger? The betrayal? Is it the narcissism? How much influence does luck have, more than effort, in our failures and successes?

Part of the greatness of this film is that it not only avoids any simple answers, but it also takes us into the awkward contradictions and internal dishonesties that help us look at the mirror each day. In contrast to the characters in the “Before Sunrise” films, where I felt we were looking at two people speaking about their generation, these are two very real individuals speaking about themselves. It’s a conversation that many of us should have, but never will. Strangely, they do not invite their daughter. Tellingly, they speak for an hour about themselves and each other, but almost never about her.

At first, we see Robert as a self-absorbed predator, a man with whom no woman could share anything more than a night of intoxication and a few weeks of passive-aggressive acrimony. But we discover that he is more compassionate and remorseful than his sinister abrasiveness has led us to believe. John Shea is so very good as a man with a chauvinist appetite, a troubled conscience and a touch of surprising tenderness. He keeps ending his sentences with the same smirk, yet it means something different every time, revealing more pain and hope with each gesture.

I fear that, in the shadow of Shea’s towering performance, Lea Thompson will be overlooked. She’s perfectly cast, almost the same pretty face we know from 1980s teen films (“Back to the Future,” “Some Kind of Wonderful“). But her innocent appearance conceals unexpected emotions over the choices she has made, which she divulges with surprising honesty.

These two talk about everything. Because we are used to the conventions of Hollywood melodrama, we anticipate right from the beginnning that Emily and Robert will eventually reunite. That prospect almost informs the narrative for us. But as booze is added to the conversation, untold longings bubble to the surface.

The film suggests that closure in such a relationship only comes with acceptance, and not a farewell. Movies about teenagers tend to romanticize first loves as the stuff of poetry, expressing something supposedly uniquely pure. This movie, about adults, shatters any notion of romantic love, regarding it as an invention only a few centuries old. We learn, instead, that it is not your first love, but your first spouse who had the privilege of sharing something primordial with you.