The crucial decision in “The Reader” is made by a 24-year-old youth, who has information that might help a woman about to be sentenced to life in prison, but withholds it. He is ashamed to reveal his affair with this woman. By making this decision, he shifts the film’s focus from the subject of German guilt about the Holocaust and turns it on the human race in general. The film intends his decision as the key to its meaning, but most viewers may conclude that “The Reader” is only about the Nazis’ crimes and the response to them by post-war German generations.

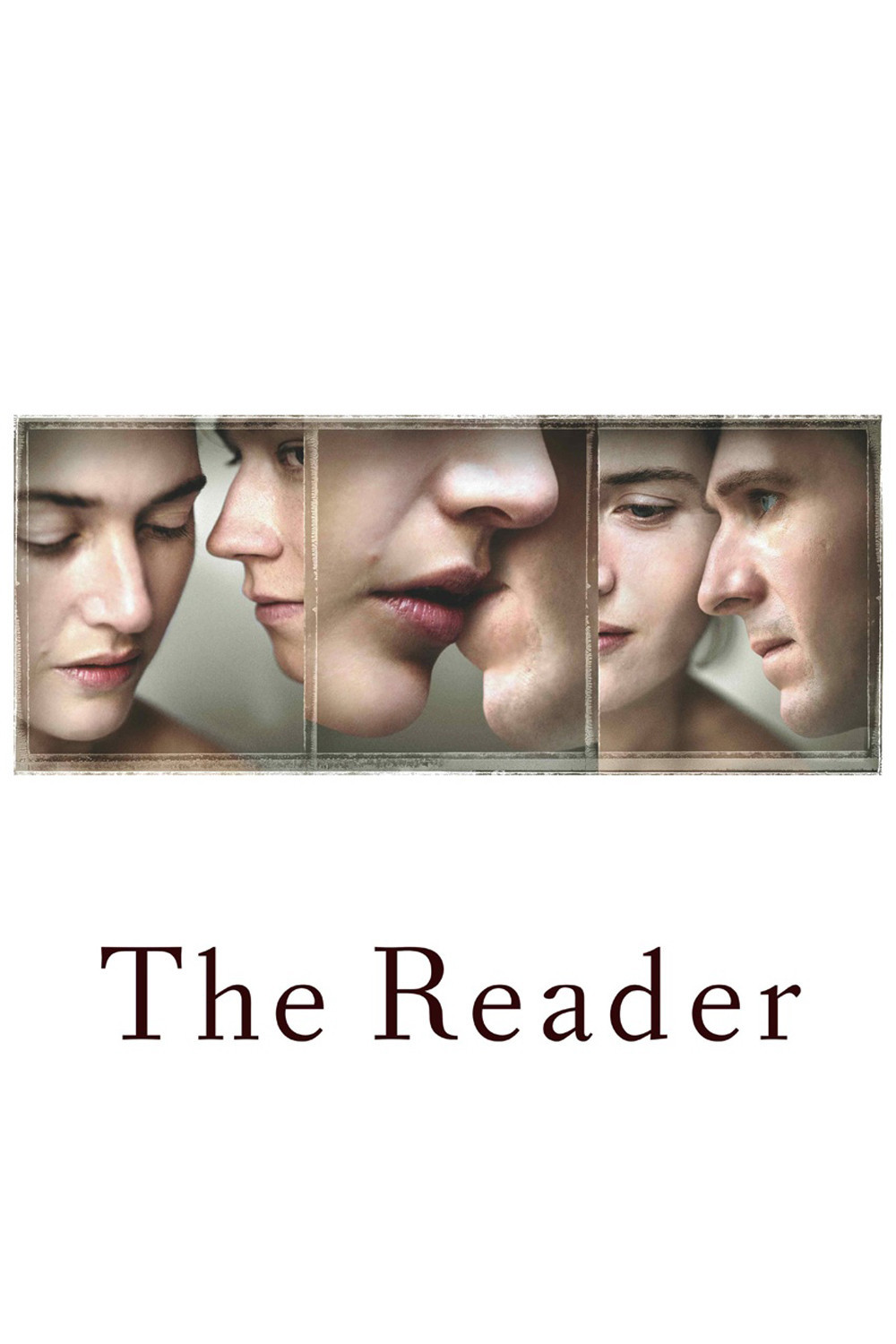

The film centers on a sexual relationship between Hanna (Kate Winslet), a woman in her mid-30s, and Michael (David Kross), a boy of 15. That such things are wrong is beside the point; they happen, and the story is about how it connected with her earlier life and his later one. It is powerfully, if sometimes confusingly, told in a flashback framework and powerfully acted by Winslet and Kross, with Ralph Fiennes coldly enigmatic as the elder Michael.

The story begins with the cold, withdrawn Michael in middle age (Fiennes), and moves back to the late 1950s on a day when young Michael is found sick and feverish in the street and taken back to Hanna’s apartment to be cared for. This day, and all their days together, will be obsessed with sex. Hanna makes little pretense of genuinely loving Michael, who she calls “kid,” and although Michael has a helpless crush on Hanna, it should not be confused with love. He is swept away by the discovery of his own sexuality.

What does she get from their affair? Sex, certainly, but it seems more important that he read aloud to her: “Reading first. Sex afterwards.” The director, Stephen Daldry, portrays them with a great deal of nudity and sensuality, which is correct, because for those hours, in that place, they are about nothing else.

One day Hanna disappears. Michael finds her apartment deserted, with no hint or warning. His unformed ego is unprepared for this blow. Eight years later, as a law student, he enters a courtroom and discovers Hanna in a group of Nazi prison guards being tried for murder. Something during this trial suddenly makes another of her secrets clear to him and might help explain why she became a prison guard. His discovery does not excuse her unforgivable guilt. Still, it might affect her sentencing. Michael remains silent.

The adult Michael has sentenced himself to a lonely, isolated existence. We see him after a night with a woman, treating her with remote politeness. He has never recovered from the wound he received from Hanna, nor from the one he inflicted on himself eight years after. She hurt him, he hurt her. She was isolated and secretive after the war, he became so after the trial. The enormity of her sin far outweighs his, but they are both guilty of allowing harm because they reject the choice to do good.

At the film’s end, Michael encounters a Jewish woman in New York (Lena Olin), who eviscerates him with her moral outrage. She should. But she thinks he seeks understanding for Hanna. Not so. He cannot forgive Hanna’s crimes. He seeks understanding for himself, although perhaps he doesn’t realize that. In the courtroom, he withheld moral witness and remained silent, as she did, as most Germans did. And as many of us have done or might be capable of doing.

There are enormous pressures in all human societies to go along. Many figures involved in the recent Wall Street meltdown have used the excuse, “I was only doing my job. I didn’t know what was going on.” President Bush led us into war on mistaken premises, and now says he was betrayed by faulty intelligence. U.S. military personnel became torturers because they were ordered to. Detroit says it was only giving us the cars we wanted. The Soviet Union functioned for years because people went along. China still does.

Many of the critics of “The Reader” seem to believe it is all about Hanna’s shameful secret. No, not her past as a Nazi guard. The earlier secret that she essentially became a guard to conceal. Others think the movie is an excuse for soft-core porn disguised as a sermon. Still others say it asks us to pity Hanna. Some complain we don’t need yet another “Holocaust movie.” None of them think the movie may have anything to say about them. I believe the movie may be demonstrating a fact of human nature: Most people, most of the time, all over the world, choose to go along. We vote with the tribe.

What would we have done during the rise of Hitler? If we had been Jews, we would have fled or been killed. But if we were one of the rest of the Germans? Can we guess, on the basis of how most white Americans, from the North and South, knew about racial discrimination but didn’t go out on a limb to oppose it? Philip Roth’s great novel The Plot Against America imagines a Nazi takeover here. It is painfully thought-provoking and probably not unfair. “The Reader” suggests that many people are like Michael and Hanna, and possess secrets that we would do shameful things to conceal.