Slavoj Zizek comes billed as a “superstar cultural theorist,” and while his celebrity is surely a fact in the recondite academic world of cultural theory, it’s safe to assume that most moviegoers will know nothing about him, though some may know enough about his accustomed milieu to harbor understandable suspicions about a film in which Zizek expounds on the intersection of ideology, philosophy and popular movies like “Jaws.”

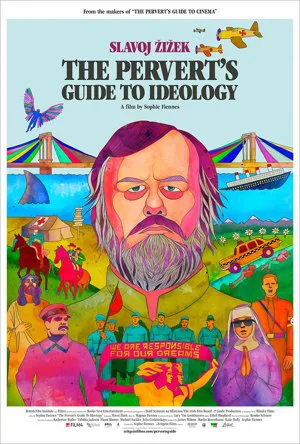

Since cultural theory, like some disciplines it draws upon (psychoanalysis, linguistics), is notorious as a dense forest of some of the most impenetrable prose ever committed to university presses, one might well wonder if “The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology,” Zizek’s latest collaboration with filmmaker Sophie Fiennes, will be similarly opaque and forbidding. Likewise, the man himself: Is the renowned intellectual one of those whose grand pronouncements make the eyes of mere mortals glaze over?

Happily, Fiennes’ film quickly answers both questions in the negative. Though its ideas are indeed heady and high-flown, they are presented in a way that’s consistently engaging and accessible. And the bearded, bulky, Slovenia-born Zizek comes across as a born raconteur and explainer, the kind of professor whose courses are deservedly his department’s most popular. You don’t have to share his materialist philosophy to find his analyses of culture and movies witty, insightful and usefully thought-provoking.

He starts with a movie that’s perfectly suited to his overarching theme. In John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic “They Live,” a man finds a bag of magical sunglasses in an abandoned church. When he dons a pair and looks, an innocuous-seeming billboard advertising computers reads, “OBEY.” Another ad showing a couple on a beach becomes “MARRY AND REPRODUCE.” Carpenter’s movie thus illustrates something that Zizek believes of all movies: that behind their obvious surface meanings are deeper ones that bespeak the culture’s fundamental tensions and imperatives.

“Ideologies,” in this sense, aren’t political doctrines codified into “isms,” but rather the fantasies and beliefs that underlie the functioning of all societies. In showing how these are reflected in the stories of individuals that movies give us, Zizek, for example, notes the similarities between “The Searchers” and “Taxi Driver“: in both films, the hero’s plunge into an orgy of violence results from trying to recover the sexual innocence of a young woman who doesn’t seem to regret its loss. What if you go to the rescue of a victim who doesn’t want to be helped? In asking that question, Zizek draws a parallel to America’s military experiences in Vietnam and Iraq—one of many instances where he teases out connections between imaginary constructs and political realities.

Another set of comparisons links “Jaws” and the Nazi ascendancy reflected in both Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” and Fritz Hipler’s 1940 anti-Semitic broadside “The Eternal Jew.” While all three films imply a threat from an intrusive Other, in Spielberg’s movie the shark is a symbol broad enough to signify everything and nothing (conservatives saw it an illegal aliens, Fidel Castro read it as capitalism itself). In Nazi cinema, however, the invasive danger has already been identified with a specific group due to “a narrative that explains [Germany’s internal] tensions in terms of a foreign intruder—the Jews.”

It’s noteworthy that, while Zizek’s background is Marxist and “Pervert’s Guide” unsurprisingly devotes some sharp critical scrutiny to the internal contradictions of Nazism, fascism and capitalism—the movies covered include “Titanic,” “Cabaret,” “The Dark Knight,” “The Sound of Music” and many others—he’s equally astringent regarding the Communist mythology that bolstered dictators like Stalin, Mao and Castro, a system based on a belief in an imaginary creature known as “the People” and that justified its many horrors thereby. However, rather than attacking those iconic leaders, Zizek says, the best way to show up such myths is by dethroning that non-existent creature; and he cites Milos Forman’s early satires as films which do just that.

In any case, he concludes, “The depressing lesson of the last decades is that capitalism has been the true revolutionizing force, even as it only serves itself.”

For many viewers, no doubt the most startling and provocative part of Zizek’s journey comes when he follows Freud down the rabbit hole of deep Western belief, where he identifies Judaism with “anxiety” and Christianity with “love.” And then, using Kazantzakis and Scorsese’s Resurrection-less “The Last Temptation of Christ” as his exemplary text, he says, “The only real way to be an atheist is to go through Christianity. Christianity is much more atheist than the usual atheism….”

While all the arguments mentioned here are more detailed and elegant in context than can be suggested in a brief summary, the climactic ones concerning religion might make some viewers want to consult Zizek’s books for further elucidation. On the whole, though, the film’s commentary is entirely lucid and intelligently entertaining, bolstered by many well-chosen film clips and Fiennes’ clever device of filming Zizek against re-created backdrops of some of the films he discusses—Travis Bickle’s apartment, Hitler’s airplane, the boat from “Jaws,” etc.

As for why the film is called “the pervert’s” guide, this reviewer noted that its end credits do not acknowledge the many movies it draws upon so copiously. That, in terms of standard filmmaking etiquette, truly is perverse.