“The Matrix Resurrections” is the first “Matrix” movie since 2003’s “The Matrix Revolutions,” but it is not the first time we’ve seen the franchise in theaters this year. That distinction goes to “Space Jam: A New Legacy,” the cinematic shareholder meeting for Warner Bros. with special celebrity guests that inserted Looney Tunes characters Speedy Gonzales and Granny into a scene from “The Matrix.” Speedy Gonzales dodged slow-motion bullets; Granny jumped in the air and kicked a cop in the face like Trinity. The 2003 animation omnibus “The Animatrix” detailed how the Matrix was created, how an apocalyptic war against robots led to human suffering being harvested to fuel a world of machines; there should be an addendum that includes this scene from “Space Jam: A New Legacy” to show what it all led to.

This is the reality that we live in—one ruled by Warner Bros.’ Serververse—and it is also the context that rules over “The Matrix Resurrections.” The film bears the name of director Lana Wachowski, returning to the cyberpunk franchise that made her one of the greatest sci-fi/action directors, but be warned that no force is remotely as strong as Warner Bros. wanting a lighter and brighter take on “The Matrix.” “The Matrix Resurrections” is a reboot with some striking philosophical flourishes, and grandiose set-pieces where things go boom in slow motion, but it is also the weakest and most compromised “Matrix” film yet.

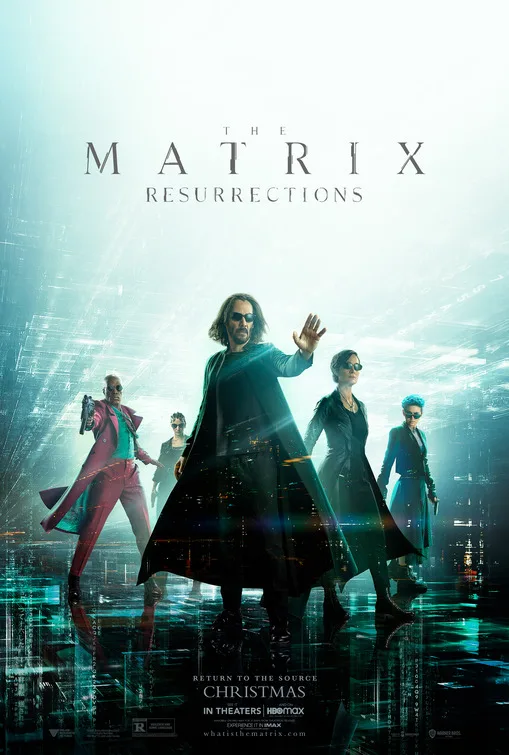

Written by Wachowski, David Mitchell, and Aleksandar Hemon, “The Matrix Resurrections” is about building from beloved beats, characters, and plot elements; call it deja vu, or just call it a convoluted clip show. It starts with a new character named Bugs (Jessica Henwick) witnessing Trinity’s famous telephone escape before having her own swooping, bullet-dodging getaway, and later throws new versions of previous characters into the the mix. The wise man of this saga, Morpheus, is no longer played by Laurence Fishburne, but Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, who looks just as cool in dark color coats and sunglasses with two machine guns in hand, but has a confusing purpose for being there. “The Matrix Resurrections” will bend over backward, bullet-time style, to explain why he is. The same goes for how heroes Neo and Trinity return, even though “The Matrix Revolutions” put a lot of care into killing them off. This is the kind of movie in which it truly doesn’t matter when you last saw the original films; your experience might be even better if you haven’t seen them at all.

It is also about making you painfully conscious of what constitutes Matrix intellectual property, as it places Keanu Reeves’ hero Neo, known in the Matrix as a brilliant video game programmer named Thomas Anderson, in a board room with a bunch of creatives, trying to come up with ideas for a sequel. He has received pressure from his boss (and Warner Bros.) after his game “The Matrix” was a hit; “bullet-time” is discussed with awe by stock geek characters as something that needs to be topped. This is one of the movie’s more reality-shifting ideas—to frame “The Matrix” as a new type of simulation, one that was created by Thomas Anderson inside the actual Matrix, as taken from his dreams that come from taking a blue pill daily, instead of the eye-opening red pill he took in the original 1999 film. And yet like many of the Warner Bros.-related meta redirections, it all ends up adding so very little to the bigger picture.

“The Matrix Resurrections” brings back the love story of Trinity (Carrie Anne Moss) and Neo, our two cyber heroes whose romantic connection gave the earlier films a sense of desperation larger than the apocalypse at hand. But here, they do not know each other, even though Thomas’ video character Trinity looks a lot like Moss. In this world, she’s a customer in a Simulatte coffee shop named Tiffany that he’s hesitant to talk to, in particular because she has kids and a husband named Chad (played by Chad Stahelski). Reeves and Moss are both invested in this whimsical arc about fated lovers, but the movie plays too much into this nostalgia as well, relying on our emotions from the past movies to largely care about why they should be together.

The movie’s greatest stake is in the mind of Thomas, one that’s been having daydreams that are clips from the “Matrix” movies, while sitting in a bathtub with a rubber ducky on his head. He receives some guidance from his therapist, played by Neil Patrick Harris, who tries to make sense of the break from reality that previously had Thomas attempting to walk off a roof, thinking he could fly. Harris’ part should remain a mystery, but let’s say it’s an unexpected role that does get you to take him seriously, including how he analyzes our own understanding of “The Matrix.” Meanwhile, it becomes apparent that just as Morpheus is a little different than we remember, there’s a new version of big baddie Smith, played by Jonathan Groff, trying to imitate Hugo Weaving’s slithering line-delivering that comes from a tightly clenched jaw. There are also copies of agents that take over bodies and wear impeccable suits and ties, chasing after the good guys.

Plenty of Matrixing is in store once Thomas believes Morpheus, but it’s more fun to witness in the movie than for anyone to explain in detail. But it includes the feeling of Thomas going back to where it all began, including a training sequence in which Reeves and Abdul-Mateen II do a rendition of the dojo scene in “The Matrix,” only this time Neo leaves with a different power that requires less movement. And as part of Neo’s journey back down the rabbit hole, there’s a breakneck, candy-colored fight sequence on a speeding train, in which Johnny Klimek and Tom Tykwer’s blitzing score seems to be powering the locomotive.

Expositional philosophizing is also a part of the “Matrix” experience, and there’s a great line here from one of the film’s villains about fear and desire being the two human modes (you can practically imagine the line scribbled in Wachowski’s notebook). But these wordy passages also conceal the movie trying to move the goal posts, that the rules of the Matrix can change however its saga about cyber messiahs needs it to keep making sequels. And while the apocalyptic, real world action has always been less exciting than the stylized anarchy up in the Matrix, that gap of intrigue is felt even more here. Behind the screens, with Neo, Trinity, and others plugged in, certain returning members of the underground land of Zion like Niobe (Jada Pinkett Smith, aged forward) try and fail to convince you that this story absolutely needs to be told, and that THIS is the ultimate world-saving chapter, even though the franchise no longer feels dangerous. That latter note becomes all the more obvious when “The Matrix Resurrections” gives us a micro, cutesy, fist-bumping descendant of the sentinel machines that used to rip human beings to shreds.

It’s the action that proves to be the purest element here, robust and snazzy—for years we have been watching directors imitate what Wachowski did with her sister Lilly with “The Matrix” films, and now we can get caught up again in her fast-paced action that marries kung fu with acrobatic gunplay, often in lush slow motion. For all of this movie’s cheesy talk about bullet-time (almost killing the fun of being in awe of it), “The Matrix Resurrections” doubles up with certain scenes that combine two different slow-motion speeds in the same frame, painting some exhilarating, big-budget frescos with dozens of flying extras and hundreds of bullets. The film’s grand finale is an action gem, as it thrives on how much adrenaline you can get from layering multiple big explosions as things suddenly crash into frame, all during a high-speed chase.

And yet once the adrenaline from a sequence like that wears off, you can’t help but think about the guy who sat near Steven Soderbergh on an airplane and watched a clip show of explosive action scenes, virtually making the director want to quit filmmaking back in 2013. There’s incredible merit in the action seen in “The Matrix Resurrections,” but those aren’t the elements that free the mind of the medium like bold storytelling, like “The Matrix” preached and then became a game-changing classic, only to become a docket for satisfying shareholders. Blue pill or red pill? It doesn’t matter anymore; they’re both placebos.

Available in theaters and on HBO Max tomorrow.