“The Majestic” is a proud patriotic hymn to America, sung in a key that may make some viewers uncomfortable. At a time when our leaders are prepared to hold trials that bypass the American justice system, here is a film that unapologetically supports the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. It is set in the early 1950s, but the parallels with today are unmistakable and frightening.

Yet this is not a sober political picture. It’s a sweet romantic comedy starring Jim Carrey, and it involves a case of mistaken identity and an attack of amnesia, those handy plot devices from time immemorial. It flies the flag in honor of our World War II heroes, and evokes nostalgic for small-town movie palaces and the people who run them. It makes us feel about as good as any movie made this year.

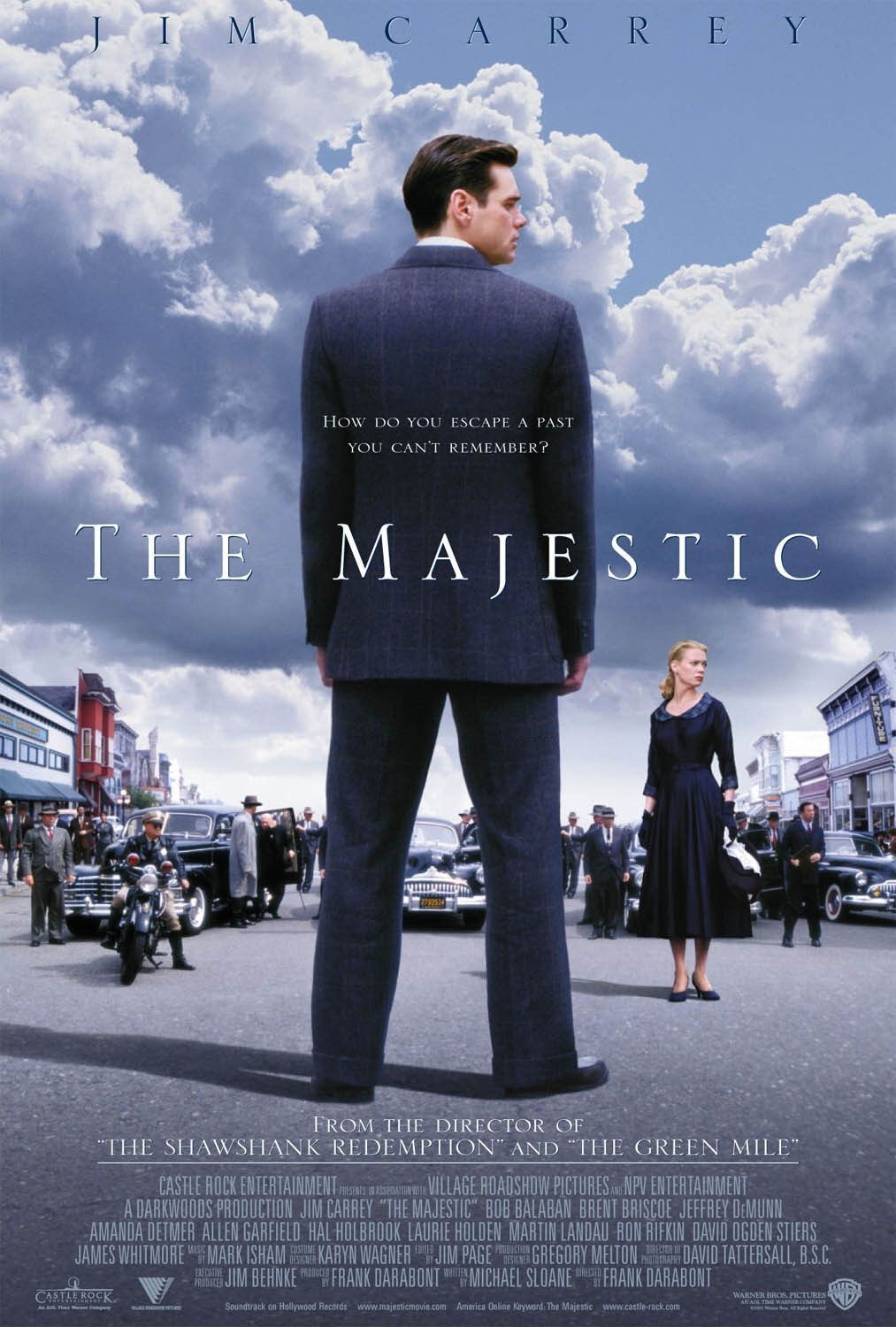

I imagine every single review of “The Majestic” will compare it to the works of Frank Capra, and that’s as it should be. Frank Darabont has deliberately tried to make the kind of movie Capra made, about decent small-town folks standing up for traditional American values. In an age of Rambo patriotism, it is good to be reminded of Capra patriotism–to remember that America is not just about fighting and winning, but about defending our freedoms. If we defeat the enemy at the cost of our own principles, who has won? Darabont, the director of “The Shawshank Redemption” and “The Green Mile,” works on big canvases with lots of characters we can sympathize with. Carrey (who has never been better or more likable) plays Peter Appleton, a shallow, ambitious Hollywood script writer who once, in college, attended a left-wing political meeting because he wanted to pick up a girl there. That wins him a place on the blacklist of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and he’s subpoenaed to testify. No one believes he was a communist (which was not against the law in any case), but to keep his job he is required to kowtow to the committee and “name names”–read a list of other communists. Since he doesn’t know any, the committee will helpfully supply it.

Depressed and confused (his starlet girlfriend has dropped him like a hot potato), Peter drives north along the coast. His car plunges off a bridge, and he’s discovered the next morning with no memory of who he is or how he got there. A kindly dog-walker (James Whitmore) takes him into the nearby town, where he looks kind of familiar to everyone. Finally old Harry Trimble (Martin Landau), who ran the local movie theater, blurts it out: This is his son Luke, lost in the war, now returned from the dead after nine years.

The town embraces Luke, and so does Adele Stanton (Laurie Holden), his onetime girlfriend. The town lost more than 60 of its young men in the war and has fallen into a depression. Somehow Luke’s miraculous return inspires them to pick up the pieces and make a new start. Why, old Mr. Trimble even decides to reopen the Majestic Theater again.

The second act of the film involves Peter’s gradual absorption in the identity of Luke. Darabont paints the town with a Capra palette: Everyone hangs out at the diner, there’s a big band dance down at the Point, Luke and Adele walk home down shady streets just like James Stewart and Donna Reed. Some, including Adele, have their doubts that this could really be Luke, but keep them to themselves.

Without getting into plot details, let me point out one moment when the screenplay by Michael Sloane does something exactly right. We know, because such stories require it, that sooner or later Peter’s true identity will be discovered. In a routine formula picture, there would be a scene where Adele feels betrayed because she was deceived, and a giant misunderstanding would open up, based on the ancient Idiot Plot device in which no one says what they should obviously say.

Not here. In one of the movie’s crucial turning points, Peter tells Adele the truth before he has to. Her reaction is based on true feelings, not misunderstandings. The movie plays fair with its plot, and with us. It even has townspeople raise the obvious questions about where Luke spent the past decade, and whether he’s built another life. So we’re on solid ground for the third act, in which Peter goes back to Los Angeles and testifies before the House committee.

The scenes of his testimony evoke memories of Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, Spencer Tracy and other Capra heroes standing up for traditional American beliefs (“That’s the First Amendment, Mr. Chairman. It’s what we’re all about–if only we live up to it”). These scenes are also surprisingly funny (Peter defends himself against charges of subversion with the defense that he was feeling horny). Hal Holbrook is the committee chairman, Bob Balaban is the mean little inquisitor, and the committee evokes fears of communism as an excuse to shelve the Bill of Rights.

Darabont makes films long enough to sink into and move around in. “The Majestic” is not as long as “The Green Mile” (182 minutes), but at 143 minutes, it’s about the same length as “Shawshank.” It needs the time and uses it. It tells a full story with three acts, it introduces characters we get to know and care about, and it has something it passionately wants to say. When “The Majestic” went into production there could have been no hint of the tragedy of Sept. 11, but the movie is uncannily appropriate right now. It expresses a faith that our traditional freedoms and systems are strong enough to withstand any threat, and that to doubt it is–well, un-American.