“We think of this place like an intensive care ward of a hospital.” So says Paul Edgecomb, who is in charge of Death Row in a Louisiana penitentiary during the Depression. Paul (Tom Hanks) is a nice man, probably nicer than your average Louisiana Death Row guard, and his staff is competent and humane–all except for the loathsome Percy, whose aunt is married to the governor, and who could have any state job he wants, but likes it here because “he wants to see one cook up close.” One day a new prisoner arrives. He is a gigantic black man, framed by the low-angle camera to loom over the guards and duck under doorways. This is John Coffey (“like the drink, only not spelled the same”), and he has been convicted of molesting and killing two little white girls. From the start it is clear he is not what he seems. He is afraid of the dark, for one thing. He is straightforward in shaking Paul’s hand–not like a man with anything to be ashamed of.

This is not a good summer for Paul. He is suffering from a painful infection and suffering, too, because Percy (Doug Hutchison) is like an infection in the ward: “The man is mean, careless and stupid–that’s a bad combination in a place like this.” Paul sees his duty as regulating a calm and decent atmosphere in which men prepare to die.

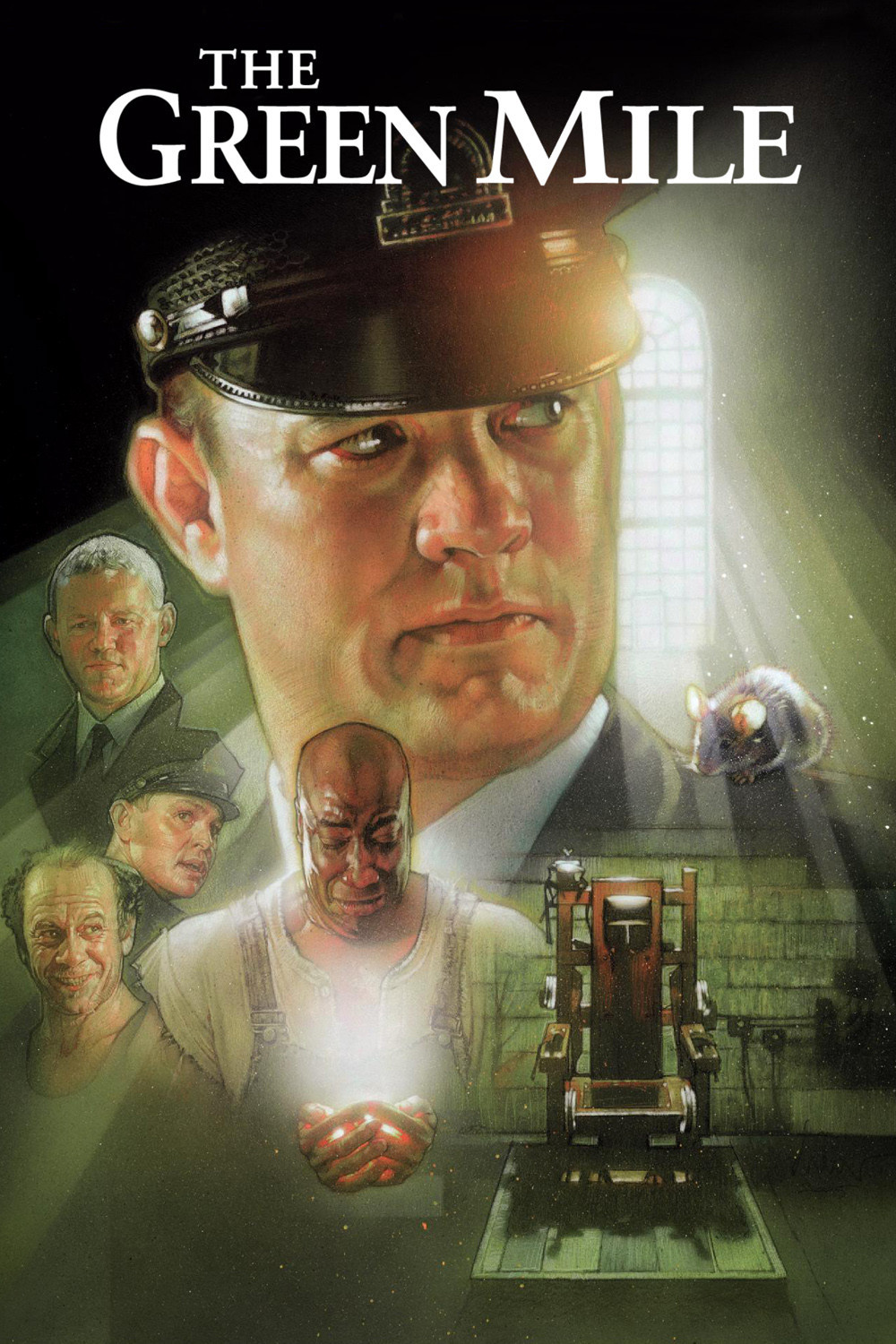

“The Green Mile” (so-called because this Death Row has a green floor) is based on a novel by Stephen King, and has been written and directed by Frank Darabont. It is Darabont’s first film since the great “The Shawshank Redemption” in 1994. That, too, was based on a King prison story, but this one is very different. It involves the supernatural, for one thing–in a spiritual, not creepy, way.

Both movies center on relationships between a white man and a black man. In “Shawshank” the black man was the witness to a white man’s dogged determination, and here the black man’s function is to absorb the pain of whites–to redeem and forgive them. By the end, when he is asked to forgive them for sending him to the electric chair, the story has so well prepared us that the key scenes play like drama, not metaphor, and that is not an easy thing to achieve.

The movie is told in flashback as the memories of Paul as an old man, now in a retirement home. “The math doesn’t quite work out,” he admits at one point, and we find out why. The story is in no haste to get to the sensational and supernatural; it takes at least an hour simply to create the relationships in the prison, where Paul’s lieutenant (David Morse) is rock-solid and dependable, where the warden (James Cromwell) is good and fair, and where the prisoners include a balmy coot named Delacroix (Michael Jeter) and a taunting monster named Wharton (Sam Rockwell).

Looming over all is the presence of John Coffey (Michael Clarke Duncan), a man whose own lawyer says he seems to have “dropped out of the sky.” Coffey cannot read or write, seems simpleminded, causes no trouble and exudes goodness. The reason Paul consults the lawyer is because he comes to doubt this prisoner could have killed the little girls. Yet Coffey was found with their broken bodies in his huge arms. And in Louisiana in the 1930s, a black man with such evidence against him is not likely to be acquitted by a jury. (We might indeed question whether a Louisiana Death Row in the 1930s would be so fair and hospitable to a convicted child molester, but the story carries its own conviction, and we go along with it.) There are several sequences of powerful emotion in the film. Some of them involve the grisly details of the death chamber, and the process by which the state makes sure that a condemned man will actually die (Harry Dean Stanton has an amusing cameo as a stand-in at a dress rehearsal with the electric chair). One execution is particularly gruesome and seen in some detail; the R rating is earned here, despite the film’s generally benevolent tone. Other moments of great impact involve a tame mouse which Delacroix adopts, a violent struggle with Wharton (and his obscene attempts at rabble-rousing), and subplots involving the wives of Paul (Bonnie Hunt) and the warden (Patricia Clarkson).

But the center of the movie is the relationship between Paul and his huge prisoner Coffey. Without describing the supernatural mechanism that is involved, I can explain in Coffey’s own words what he does with the suffering he encounters: “I just took it back, is all.” How he does that and what the results are, all set up the film’s ending–in which we are reminded of another execution some 2,000 years ago.

I have started to suspect that when we talk about “good acting” in the movies, we are really discussing two other things: good casting and the creation of characters we react to strongly. Much of a performance is created in the filmmaking itself, in photography and editing and the emotional cues of music. But an actor must have the technical and emotional mastery to embody a character and evoke him persuasively, and the film must give him a character worth portraying. Tom Hanks is our movie Everyman, and his Paul is able to win our sympathy with his level eyes and calm, decent voice. We get a real sense of his efficient staff, of the vile natures of Percy and Wharton, and of the goodness of Coffey–who is embodied by Duncan in a performance that is both acting and being.

The movie is a shade over three hours long. I appreciated the extra time, which allows us to feel the passage of prison months and years. Stephen King, sometimes dismissed as merely a best-seller, has in his best novels some of the power of Dickens, who created worlds that enveloped us and populated them with colorful, peculiar, sharply seen characters. King in his strongest work is a storyteller likely to survive as Dickens has, despite the sniffs of the litcrit establishment.

By taking the extra time, Darabont has made King’s “The Green Mile” into a story which develops and unfolds, which has detail and space. The movie would have been much diminished at two hours–it would have been a series of episodes without context. As Darabont directs it, it tells a story with beginning, middle, end, vivid characters, humor, outrage and emotional release. Dickensian.