“The Island” runs 136 minutes, but that’s not long for a double feature. The first half of Michael Bay’s new film is a spare, creepy science fiction parable, and then it shifts into a high-tech action picture. Both halves work. Whether they work together is a good question. The more you like one, the less you may like the other. I liked them both, up to a point, but the movie seemed a little too much like surf & turf.

The first half takes place in a sterile futuristic environment where the inhabitants wear identical uniforms (white for the citizens, black for their supervisors). Big-screen TVs broadcast slogans and instructions, and about twice a day everybody gathers before them for the Lottery. This sealed world, its citizens believe, has been created to protect them from pollution that has poisoned the Earth. There is, however, one remaining “pathogen-free zone,” which looks a lot like a TV commercial for “The Beach.” Winners of the Lottery get to go there.

Yeah, sure, we’re thinking. But the citizens in the white suits don’t think very deeply; “they’re educated to the level of 15-year-olds,” we’re told. There was a time when that would have made them smarter than most of the people who ever lived, but in this future world education has continued to degrade, and we see adults reading aloud from Fun With Dick and Jane, a book that on first reading I found redundant and lacking in irony.

The true nature of this sealed world is not terrifically hard to guess; even those who failed to see through “The Village” may decode its secret. But the inhabitants are childlike and blissful, all except for a few troublesome characters like Lincoln Six Echo (Ewan McGregor), who wants bacon for breakfast but is given oatmeal. This inspires him to develop what all closed systems fear, a curiosity. “Why is Tuesday night always tofu night?” he asks his supervisor. “What is tofu? Why can’t I have bacon? Why is everything white?” Then one day he sees a flying bug, where no bug should be, or fly.

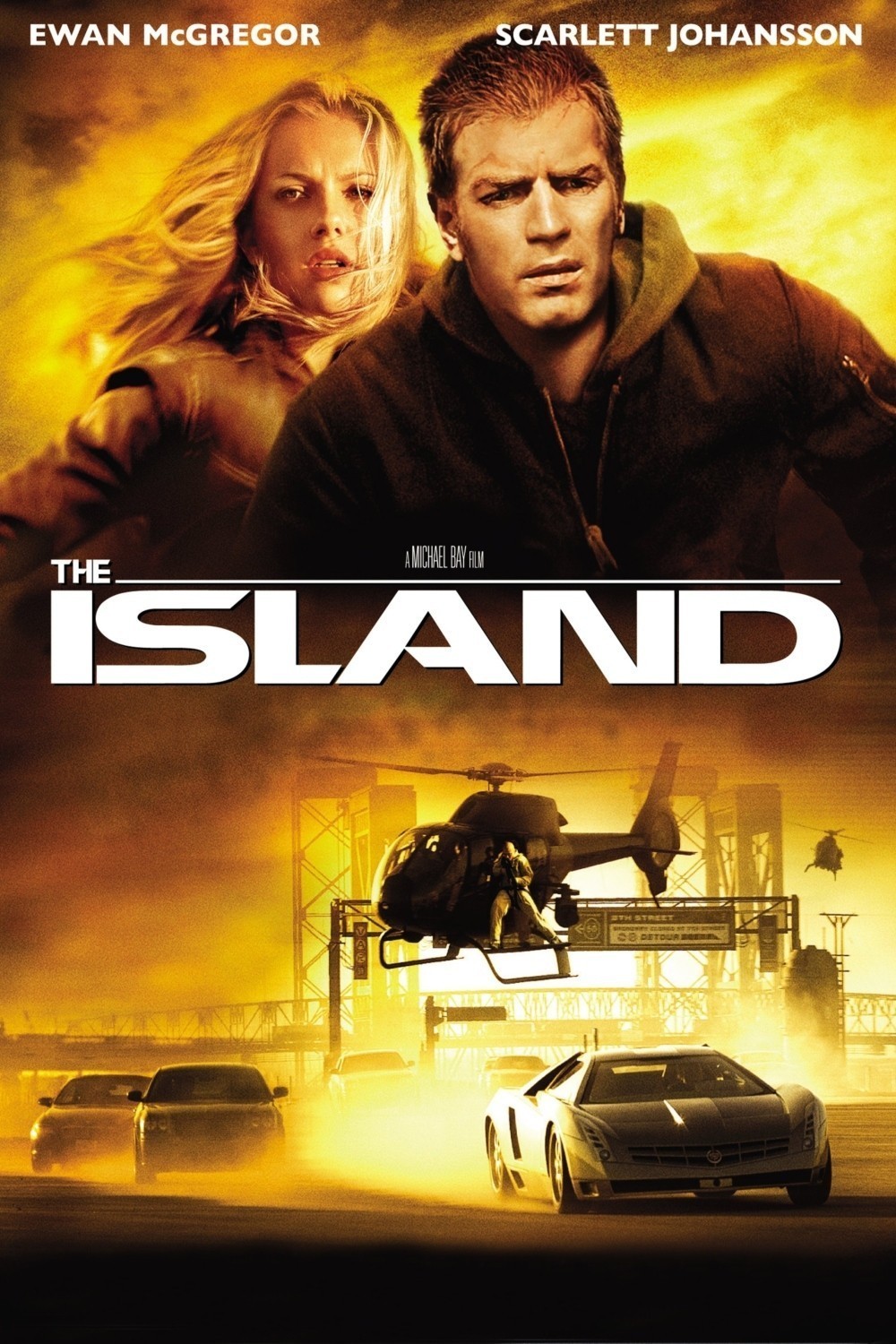

Sidestepping some intervening spoilers, I can move on to the second half of the movie, in which Lincoln Six Echo and the equally naive Jordan Two Delta (Scarlett Johansson) escape from the sealed world, and are chased by train, plane, automobile, helicopter and hover-cycle in a series of special effects sequences that develop a breathless urgency. How the heroes manage to discover the underlying truth about their world while moving at such a velocity suggests they are quicker studies than we thought.

The movie never satisfactorily comes full circle, and while the climax satisfies the requirements of the second half of the story, it leaves a few questions unanswered. We wonder, for example, why a manufacturing enterprise so mammoth could have been undertaken in secret. Were government funds involved? We don’t need to know the answers to these questions, it’s true, but they would have allowed Bay (“Armageddon“) to do what the best science fiction does, and use the future as a way to critique the present. Does stem cell research ring a bell?

“The Island” has certain special effects, not its largest or most sensational, that reminded me of the creativity in a film like Spielberg’s “Minority Report.” For example, little ladybug-like robots that crawl up your face and into your eye sockets, and transmit information from your brain before working their way through your plumbing and being expelled like kidney stones. I hate it when that happens. And consider the effective way CGI is used to show the actors interacting with themselves.

McGregor and Johansson do a good job of playing characters raised to be docile, obedient and not very bright. The way they have knowledge gradually thrust upon them is carefully modulated by Bay, so that we can see them losing their illusions almost in spite of themselves. Michael Clarke Duncan has only three or four scenes, but they’re of central importance, and he brings true horror to them. Sean Bean has the Sean Bean role, as a smug corporate monster. And the beloved Steve Buscemi plays an important character who has brought all of his bad habits into the sterile future world.

Buscemi is an engineer, or maybe a janitor, and lives in what must be the boiler room. All closed systems, no matter how spotless and pristine, always have an area filled with rusty machinery, cigarette butts, oily rags, and a guy who reads dirty magazines and knows how everything really works. Even in “Downfall,” the harrowing drama about the last days of Hitler, there was a boiler room in the bunker where Eva Braun and her buddies could sneak away for a smoke. The Buscemi character turns out to be surprisingly well-informed and helpful, but then again, if the plot had to depend on characters educated only to the level of 15-year-olds, we might still be in the theater.

Footnote (spoiler warning). It was a little eerie, watching “The Island” only a month after reading Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel Never Let Me Go. Both deal with the same subject: Raising human clones as a source for replacement parts. The creepy thing about the Ishiguro novel is that the characters understand and even accept their roles as “donors,” while only gradually coming to understand their genetic origins. They aren’t locked up but are free to move around; some of them drive cars. Why do they agree to the bargain society has made for them? The answer to that question, I think, suggests Ishiguro’s message: The real world raises many of its citizens as spare parts; they are used as migratory workers, minimum-wage retail slaves, even suicide bombers. “The Island” doesn’t go there, but then did you expect it would?