“How can you know what you’d really do to stay alive, until you’re asked? I know now that the answer for most of us is–anything.” So says a member of the Sonderkommandos, a group of Jews at the Auschwitz II-Birkenau death camp, who sent their fellow Jews to die in the gas chambers, and then disposed of the ashes afterward. For this duty they were given clean sheets, extra food, cigarettes and an extra four months of life. With the end of the war obviously drawing closer, four months might mean survival. Would you refuse this opportunity? Would I? Tim Blake Nelson’s “The Grey Zone” considers moral choices within a closed system that is wholly evil. If everyone in the death camp is destined to die, is it the good man’s duty to die on schedule, or is it his duty to himself to grasp any straw? Since both choices seem certain to end in death, is it more noble to refuse, or cooperate? Is hope itself a form of resistance? These are questions no truthful person can answer without having been there. The film is inspired by the uprising of Oct. 7, 1944, when members of the 12th Sonderkommando succeeded in blowing up two of the four crematoria at the death camp; because the ovens were never replaced, lives were saved. But other lives were lost as the Nazis used physical and mental torture to try to find out how the prisoners got their hands on gunpowder and weapons.

I have seen a lot of films about the Holocaust, but I have never seen one so immediate, unblinking and painful in its materials. “The Grey Zone” deals with the daily details of the work gangs–who lied to prisoners, led them into gas chambers, killed them, incinerated their bodies, and disposed of the remains. All of the steps in this process are made perfectly clear in a sequence, which begins with one victim accusing his Jewish guard of lying to them all, and ends with the desperate sound of hands banging against the inside of the steel doors. “Cargo,” the workers called the bodies they dealt with. “We have a lot of cargo today.” The film has been adapted by Nelson from his play, and is based on part on the book Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account , by Miklos Nyiszli, a Jewish doctor who cooperated on experiments with the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele, and is portrayed in the film by Allan Corduner. Is it a fact of human nature, that we are hard-wired to act for our own survival? That those able to sacrifice themselves for an ethical ideal are extraordinary exceptions to the rule? Consider a scene late in the film when Rosa and Dina (Natasha Lyonne and Mira Sorvino), two women prisoners who worked in a nearby munitions factory, are tortured to reveal the secret of the gunpowder. When ordinary methods fail, they are lined up in front of their fellow prisoners. The interrogator repeats his questions, and every time they do not answer, his arm comes down and another prisoner is shot through the head.

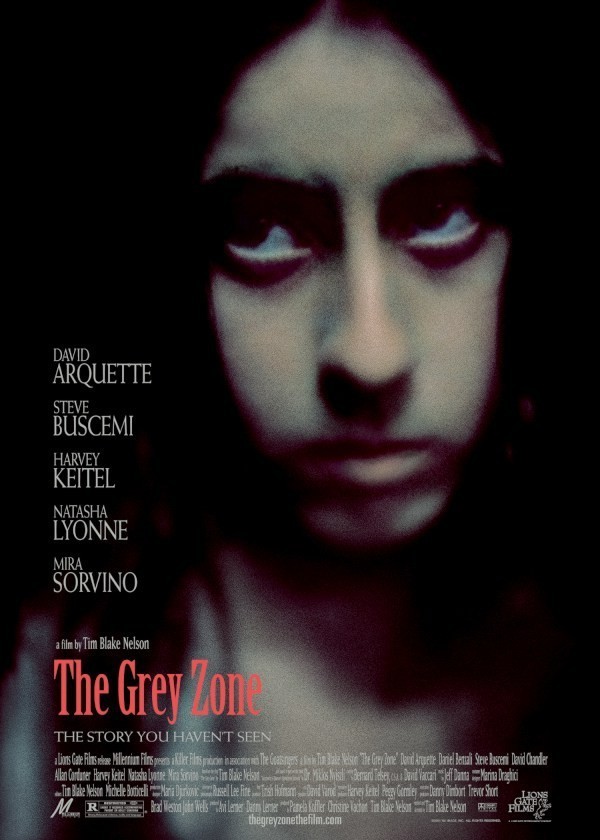

What is the right thing to do? Betray the secrets and those who collaborated? Or allow still more prisoners to be murdered? And if all will die eventually anyway, how does that affect the choice? Is it better to die now, with a bullet to the brain, than after more weeks of dread? Or is any life at all worth having? The film stars David Arquette, Daniel Benzali, Steve Buscemi and David Chandler as the leaders of the Sonderkommandos, and Harvey Keitel as Muhsfeldt, an alcoholic Nazi officer in command of their unit. Although these faces are familiar, the actors disappear into their roles. The Jewish work force continues its grim task of exterminating fellow Jews, while working on its secret plans for a revolt.

Then an extraordinary thing happens. In a gas chamber, a young girl (Kamelia Grigorova) is found still alive. Arquette rescues her from a truck before she can be taken to be burned, and now the Jews are faced with a subset of their larger dilemma: Is this one life worth saving if the girl jeopardizes the entire revolt? Perhaps not, but in a world where there seem to be no choices, she presents one, and even Dr. Nyiszli, so beloved by Mengele, helps to save the girl’s life. It is as if this single life symbolizes all the others.

In a sense, the murders committed by the Nazis were not as evil as the twisted thought that went into them, and the mental anguish they caused for the victims. Death occurs thoughtlessly in nature every day. But death with sadistic forethought, death with a scenario forcing the victims into impossible choices, and into the knowledge that those choices are inescapable, is mercilessly evil. The Arquette character talks of one victim: “I knew him. We were neighbors. In 20 minutes his whole family and all of its future was gone from this earth.” That victim’s knowledge of his loss was worse than death.

“The Grey Zone” is pitiless, bleak and despairing. There cannot be a happy ending, except that the war eventually ended. That is no consolation for its victims. It is a film about making choices that seem to make no difference, about attempting to act with honor in a closed system where honor lies dead. One can think: If nobody else knows, at least I will know. Yes, but then you will be dead, and then who will know? And what did it get you? On the other hand, to live with the knowledge that you behaved shamefully is another kind of death–the death of the human need to regard ourselves with favor. “The Grey Zone” refers to a world where everyone is covered with the gray ash of the dead, and it has been like that for so long they do not even notice anymore.